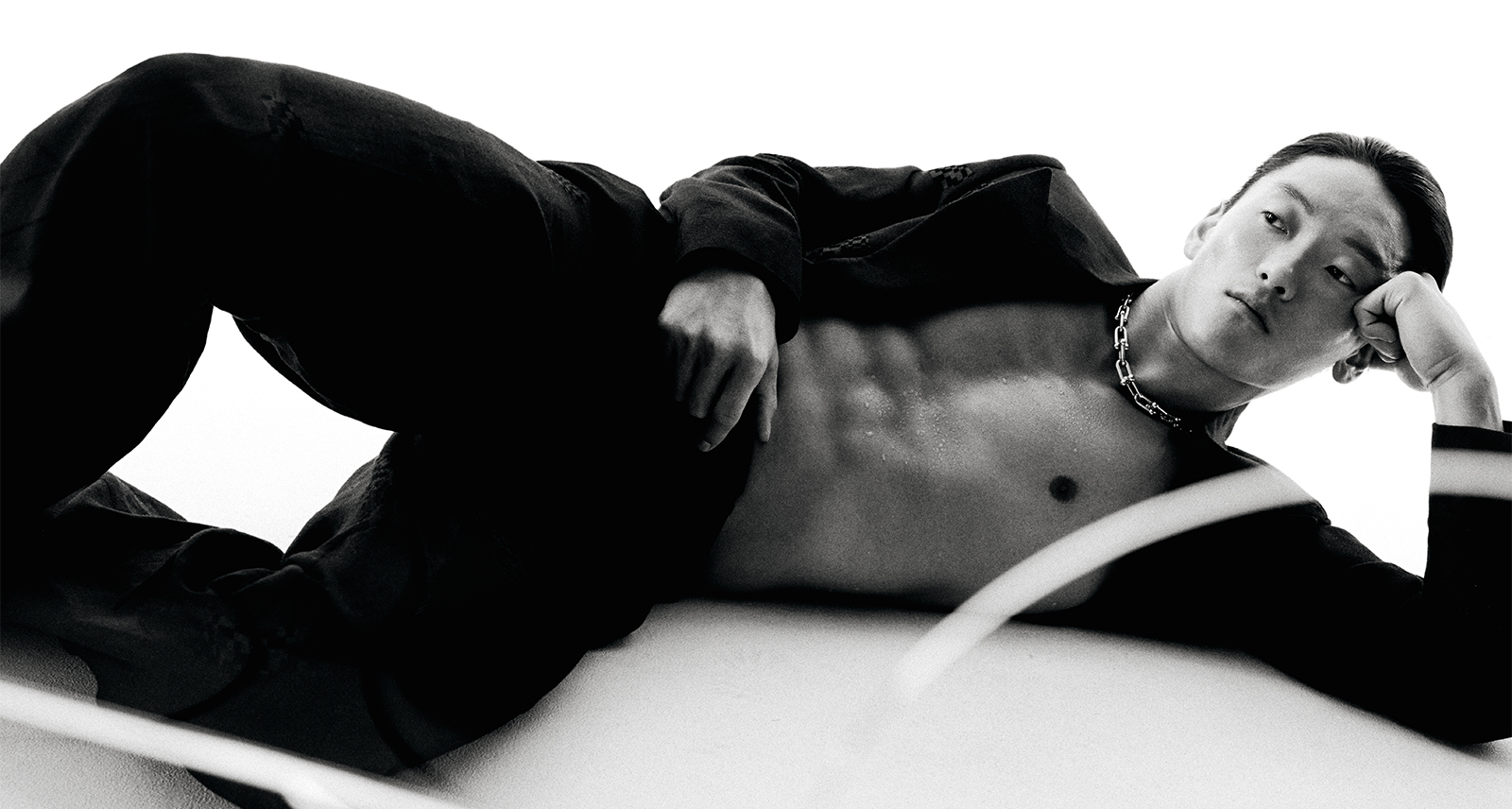

A Man Worth Listening To: Adrian Grenier

Many people want Adrian Grenier to legally change his name to Vincent Chase. Naturally. It’s hard to think of Grenier as anyone but the narcissistic playboy/movie star he played for eight seasons on HBO’s male-bonding comedy-drama Entourage—a role he reprises this summer in the movie version of the series. Hell, when I catch him on the phone, he’s cruising down Sunset Blvd., top down, on his way to a meeting with his agent. Dude even runs his errands like Vince.

In truth, Grenier is much like his fictional counterpart: he’s a doe-eyed actor navigating the vapid terrain of Hollywood with his own close circle of friends and a trusty agent. Where he diverges from Vince, however, is in the way he dissects that terrain and the world surrounding it. He’s directed a swath of socially conscious documentaries, from 2010’s Teenage Paparazzo, a critique of our celebrity obsession from the eyes of a 14-year-old paparazzi photographer, to this year’s 52, an eye-opening look at the way ocean noise pollution is quickly becoming a major threat to marine mammals. Talk to the 38-year-old long enough and you’ll realize he wears his big, bleeding heart on his sleeve. Vince will flirt with the bunnies at a Playboy mansion party; Grenier will stress over the way the whole thing reinforces the heteropatriarchy. The irony of this all is not lost on the actor.

So in the Entourage movie, Vince decides to take a stab at becoming a director. You’re an actor-turned-director in real life, too! How similar is Vince the character to Adrian the person?

Probably about 62.5% or so.

“Something

Entourage gave me was a little bit of levity. Everything doesn’t have to be so serious.”

That’s awfully precise. Was this the type of role you envisioned yourself playing when you first came to Hollywood?

Oh, not at all. I resisted it at first, in fact. The character of Vince was still just a blank canvas in a lot of ways. So I only could see the misogyny, the materialism and the superficial parts of it. It wasn’t really something I was interested in. But when I talked to Doug, he assured me all that stuff was just the backdrop. It was a reality that exists and the world these guys were thrust into. But ultimately, he was going to allow me to create a character that was deeper than that.

What kind of actor did you initially aspire to become?

I wanted to be in the movies that I loved—dark, gritty indie films. But, you know, it wasn’t up to me. Something Entourage gave me was a little bit of levity. Everything doesn’t have to be so serious. You don’t have to deconstruct everything.

Did you have trouble pretending to party on a show that’s largely about partying?

I did, I did. It was kind of funny. Doug would come up to me between takes and tell me to smile already because we were having the best time. And I’d be like, ‘It doesn’t say that in the script!’ And he’d say, ‘It doesn’t have to! That’s just the show.’ So now I just smile arbitrarily at all times, whenever possible. I’m actually a brooding, serious guy, believe it or not. People don’t appreciate how much of a stretch that character is for me, on some level.

I watched your documentary Teenage Paparazzo. You strike me as someone who’s quite apprehensive of fame and celebrity culture.

Absolutely. It’s something I’ve always questioned and been wary of. And I’ve sometimes felt cautious of the way Entourage has dealt with it. I don’t think a lot of people question whether or not the show’s degrading to women or misogynistic or totally materialistic. I mean, the fact is that guys talk like that and there’s certain realities to that culture, so I think it would be disingenuous to leave it out. But, on the other hand, I think the show has a lot of really valuable lessons. In fact, the strong female characters in the show really prove that.

What is it that you hate about celebrity culture?

I don’t have very much hate in my body.

Okay, maybe hate is a strong word.

There are certainly things about celebrity culture that I find frustrating. But I don’t know if it’s the celebrity that’s to blame necessarily. I think it’s really the complex system of media and attention and distraction and motivation and incentives that’s overtaken American culture. Celebrity culture is just one result of that. It’s a symptom of a bigger problem.