The Tragic Allure of Boxing When You’re Not Able to Throw a Punch

Due to a congenital deformity of the hands, I cannot make a fist.

In theory, there is no fighting for me, ever. My dad had the same disability — several fingers are fused in the bone, and twisted in other ways — and yet the configuration of his fingers was just different enough for him to be able to close them, and he boxed as a teenager.

I can’t really fathom the disadvantage he was at. We both had surgeries as infants, to remove fused bone and finger fragments, and we both had exposed nerve endings on stumps. To this day, if I rap one of these it sends a funny-bone shock right up my arm. It doesn’t hinder me much in other ways, but I can’t imagine actually punching anything; it would be too painful. My dad had had gangrene, too, after one of his surgeries, which led to another bit of finger being lopped off. His fists were not solid, could do little damage, and they probably hurt him. He was really in no condition to punch.

Yet punch he did, and he never talked about his success or lack of it. His generation was different: they were not allowed to sit things out due to minor disability or allergy. It was assumed everyone had a disadvantage of some sort; the point of painful sports and exams was to see how you could overcome that disadvantage.

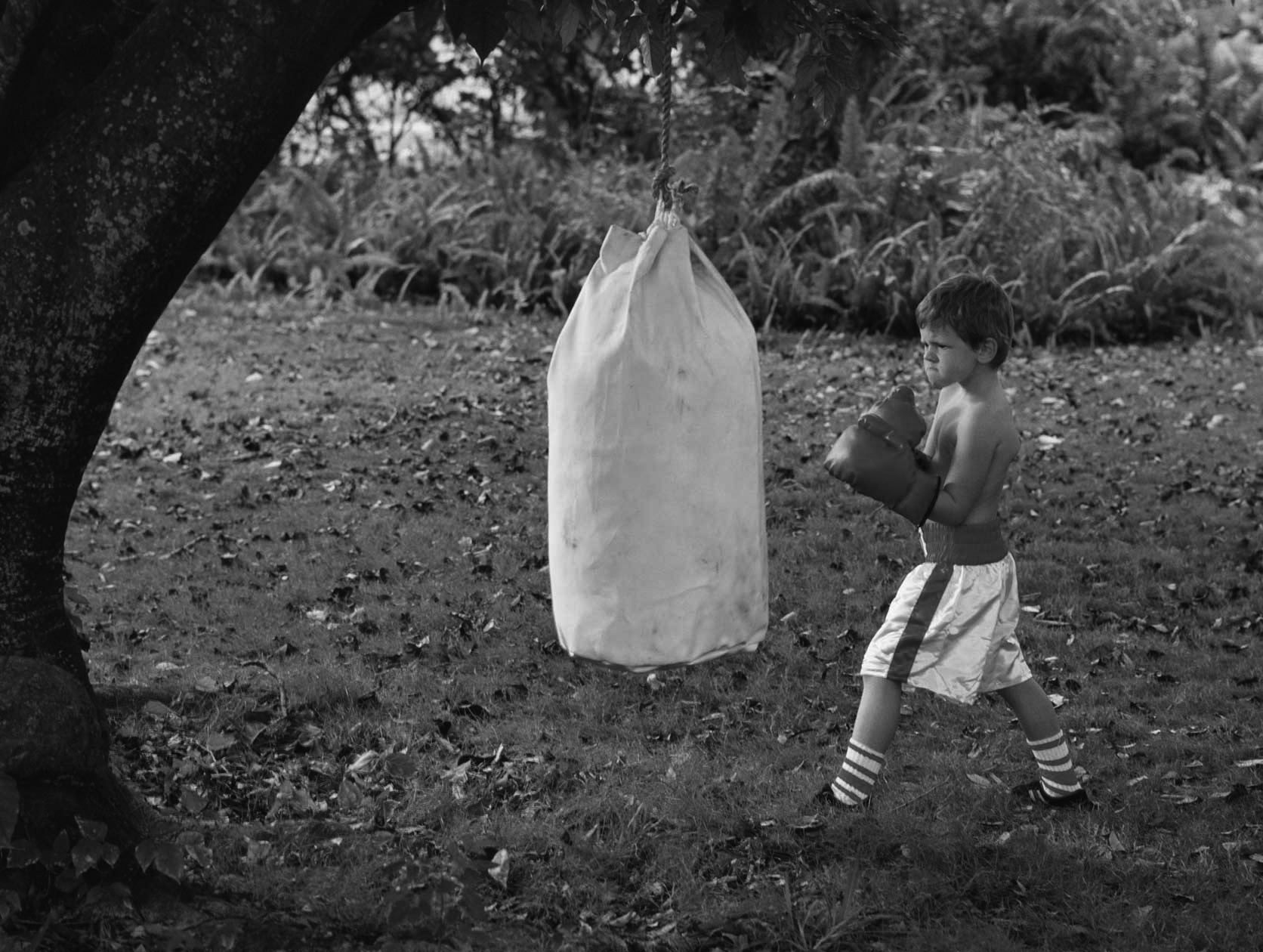

He bought me some gloves as a child that I could hardly pull on. He installed a speed bag in the basement. His walloping of it shook the foundations.

“I can’t help but think, dream, of hitting. I still have fantasies about bar fights, about smashing the jerk’s jaw, then bringing my knee up into his nose, snapping his head back.”

He had a bit of a temper, and once, on receiving some bad news in his office, punched a wall in front of his secretary, putting a hole in it. (I can’t imagine this was a pleasant moment for the secretary. But this was in the 1970s, so he was not charged with creating a hostile workplace; he just quietly had the wall repaired on his own dime.) His hand was cut, and he had to go to hospital. He had a little fun with this. The attending doctor had a shock on seeing this mangled, bleeding hand: he didn’t realize it had been mangled to start with. He thought he was witnessing a horrific injury. My dad let him puzzle over it for a moment before explaining it was just a cut.

I wanted to be a hitter too. When I was 11, I was at a private school in England and some dispute arose between me and a tall, thin Indian boy called Gunraj. Word went around that I had been insulted somehow and that I was expected to defend my honour.

I remember standing in front of him in a concrete playground and swinging wildly, upwards, once, with an open hand, and my knuckle catching him on a front tooth. We both froze. The next thing I knew there was blood running from his nose. I don’t even think I had hit him on the nose; I think he just developed a nosebleed.

He turned away. There were smirks and smacks on the back. I felt an unexpected pleasure. But my hand had a cut on it and started to swell and ache. Later in the afternoon I heard that Gunraj was crying. I passed him sitting on the ground, against a wall, blood running down his chin, playing the victim.

And then I realized he was. I had not wanted to hit him, had nothing against him really. And my hand was hurting like a throbbing heart.

I was bullied in my turn. Once standing in line for lunch a group of sixth-formers — 18-year-olds — barged in front of me. “Excuse me,” I said in my unbroken chorister’s voice (I sang first treble). One of them turned and peered down at my pretty blond head. “Do you know,” he said slowly, “you wouldn’t even have to bend over to suck me off?” My own silence was more humiliating than the guffaws that followed.

And so I can’t help but think, dream, of hitting. I still have fantasies about bar fights, about smashing the jerk’s jaw, then bringing my knee up into his nose, snapping his head back. These are quite graphic and bloody. I wonder if women have these.

When it came time to see a real fight with my dad, when I was 14, I could not have been more excited. I did not anticipate the violence of dreams: I craved heroism and strength, and the company of my dad’s friends, which meant an entrance into adulthood.

This was in Halifax, which was a big boxing town. It was also the heyday of professional boxing in the United States: the decade of Ali and Foreman and Frazier. In Halifax there were a couple of famous boxing families: the white Clarkes would fight the black Grays.

In the early ’70s, the big bouts in Halifax took place in the Forum, a concrete cavern in the North End also used for agricultural shows. It always smelled of hay and urine, even when used for monster truck racing. My father had a group of friends, middle-class professional men, who had ringside season tickets to the fights. There was a doctor, a lawyer, a developer, a guy who owned a chain of clothing stores, a performing arts programmer.

One of them had quit being a lawyer to be a professional heavyweight boxer’s manager. The fighter’s name was Trevor Berbick — if you look him up you’ll see he was WBC heavyweight champion of the world in 1986, and was the last man to fight Mohammed Ali (Berbick won; Ali was 39). My dad’s friend arranged for me and some friends to go and interview Berbick at his gym for our high school newspaper. The gym was in the North End, the black end, and in an unheated garage. Berbick answered our questions while he skipped and did sit-ups on the incline board. He put his arms around the three of us to pose for a photograph. We were very proud of ourselves, mostly, I think, for just stepping into the North End at all.

“I still watch boxing whenever I can, looking for the violence, hoping for it, then turning away when it comes.”

My dad’s friends were exciting. I was skinny and pubescent, and five full-grown men standing together seemed impossibly giant, like a special-forces team. Everything they said was a joke; everything was a light insult too. When they came over to our house, there was booze, lots of it, and booming laughter, and cologne. They had stories about firing guns and flying planes. I would be assigned ice duty, twisting the cubes out from the plastic trays, refilling them. I was the master of swizzle sticks and lemon wedges. I learned to pour the beer at an angle.

The Forum itself was like a descent into a primal state. It was dank and dirty. I had not realized the crowd would be drunk, the shouts blood-thirsty and frequently racist.

When pro fights start, you understand why it is dangerous to watch them or to be in the same room with them. They are so shocking, so frightening, so goddam awful, your body is in full-throttle adrenaline from the first bell. I was ringside. I could see the sprays of sweat, feel the impacts, see the welts start to come up under eyes and over kidneys. The screaming for harm and death grew ecstatic. It is almost impossible to watch an intense fight without wanting to stand up and stop it, and so almost everybody does stand up, at the most violent moments, until you have a crowd of 6,000 people who want to fight.

The last bout of that night had a referee who was somewhat laissez-faire, and it ended with an unopposed flurry of blows that went on just a second too long. A man’s head was pummelled and the blood from the cut over his eye started to spray. Since I was ringside, I was spattered with it. It was warm on my face and hands. I remember looking at the dots on my pale summer sportsjacket and feeling horror turn into sickness.

But the fight was ended and cheering began for the fighters’ mutual bravery. As I followed the bubbling crowd out with my dad and his happily babbling friends, I felt the horror turn to euphoria — the high you get after you narrowly miss being hit by a taxi or falling out of a window. You giggle.

I told all my friends for weeks after how exciting it had been. But it had been sickening and cold and I never wanted to see it again.

Of course I did — and I still watch boxing whenever I can, looking for the violence, hoping for it, then turning away when it comes.

Trevor Berbick went to jail for raping a 15-year-old babysitter in 1992 and was murdered in a Jamaican church-yard, his head bashed in by a steel pipe, in 2006.

My son has the same hands as me and my dad and cannot make a fist and is just as excited about hitting. He asked me, on the way to school one day, if I had ever been in a fight, and I told him about what I had done to Gunraj when I was 11. And there on the Canadian street I started to cry. He was baffled: why was I crying when I had won the fight? I told him that guys like us can never get in fights because we will always lose. He doesn’t believe me and he will one day hit someone and find out.