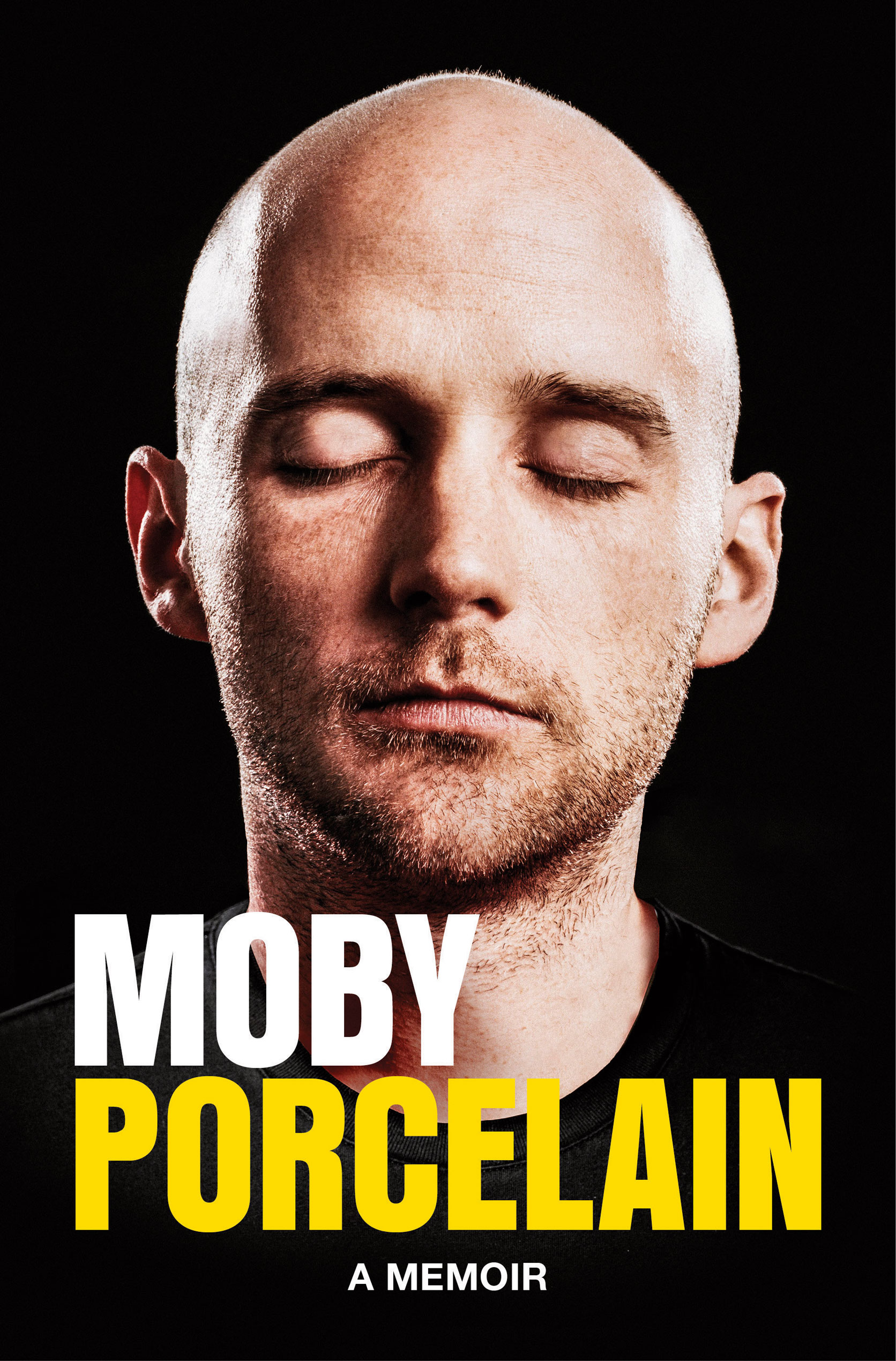

Moby Talks Selling Out, Eminem and His New Memoir Porcelain

You’re too old, let go, it’s over — nobody listens to techno!” It’s hard to think of Moby without hearing those words, even today. Back in 2002, Eminem’s notorious epithet against the electro icon on “Without Me” — the result of a very public feud between the two artists — was a devastating right hook. Its timing was impeccable: Moby was feeling the brunt of a cultural backlash.

While Play, his 1999 electro-soul smash, was the first LP to turn a techno geek into a pop superstar, critics took umbrage with where they were hearing it: SUV ads, Nike spots, movie trailers. It was the first album to have all — every single one — of its tracks licensed for commercial use. Moby would become the early aughts’ poster boy for selling out, derided for making electronica (read: edgy, underground) safe enough for corporate America (read: not cool). His career took a hit, and he’s kept a low profile since.

But here’s the thing: these days, everyone listens to techno. What’s more, song licensing has become the new norm; amid a struggling music industry, bands can’t survive without hawking their tunes at ad execs. Turns out Moby’s only crime was figuring out the game sooner than the rest of the world. His influence is now everywhere. At 50, though, he’s blissfully indifferent about how he’s perceived. The reclusive New Yorker is content staying out of the spotlight, quietly crafting boundary-pushing albums (like this year’s meditative Long Ambients1: Calm. Sleep.) primarily for himself. Appropriately, his new memoir, Porcelain, captures his pre-fame rave days in the ’90s, back when his focus, like today, was on music and good vibes, not TMZ headlines. It seems Moby’s actually taken Eminem’s advice: he’s let go. And that may just be the sweetest revenge yet.

Should I call you Moby or Richard?

I’ve been called Moby since I was born. I mean, my legal name is Richard Melville Hall. [1] But my parents started calling me Moby, as a nickname, since I was 10 minutes old. Somehow it stuck.

Considering your great literary lineage, did you feel it would be criminal to not try writing a book?

A lot of musicians and public figures, when they make their memoir, they simply hire a writer to do it for them. And sometimes that really works out; The Dirt by Mötley Crüe almost benefitted from the musicians not writing their own book. Originally I wanted to do that, but my literary agent reminded me I’m related to Herman Melville, so at the very least I should try to write my own book. And once I started writing it, I really fell in love with the process. It became almost a compulsion. But I can’t be so presumptuous as to think I’ve availed myself of the literary DNA of Herman Melville. The best I can hope for is that 0.01 per cent of his talent rubbed off on me.

I love making records, but I don’t really expect anyone to notice.

Parts of this book are quite, um, fleshly. Did you have any anxiety about revealing such intimate details about yourself?

One concern I had is if you’re writing about your past sex life, what potential damage does that do to future people you might date? [2] If I started dating someone, I really wouldn’t want to read about her having sex with someone else. So, to that end, I feel potentially uncomfortable. But, apart from that, I feel we live in a culture where people expend so much energy trying to present themselves as people they aren’t. And I get really tired of that. Like the hip-hop artist pretending they’re tougher than they are, and the indie rockers pretending they’re cooler than they are, and the pop stars pretending they’re younger and sexier than they are. I think there’s a much more interesting benefit and utility to people just honestly being who they are.

On the note of being yourself, what was it like being this skinny, white, Christian vegan trying to make it in the early ’90s New York club scene?

At the time it made perfect sense to me, but in hindsight, I realize how strange it was: I had long hair, I was vegan, I was sober, I was teaching bible study during the day, and at night I was DJing at hip-hop clubs and gay discos and sex parties. And at most of these events, I was the only white person there; Latino and African-American people primarily attended them. But it’s one of the things that really attracted me to Lower Manhattan in those days. I felt honoured that I was allowed to be a part of those worlds. And it just seemed more interesting to me. A lot of the people I’d grown up with had gone down this bland rabbit hole of late ’80s indie rock and liberal arts literary publications. The white world back then was really insular and dull. Going to a bar with people holding beers and listening to indie rock bands while vaguely nodding their heads just can’t compete with 500 gay African Americans and Latinos dancing like crazy. One thing about the early house music and hip-hop world of that time was they were completely non-ironic and in no way restrained or cautious.

So, the polar opposite of these irony-laden times.

You know, irony can be fun, but to me, irony is like vanilla extract: a little bit goes a really long way. You certainly don’t want to drink a glass of vanilla extract.

Much of this book chronicles your failures in the mid-’90s, [3] just before Play, which you thought would be your swan song, but became this freak global smash. What did experiencing both extremes teach you?

That you don’t learn anything from success, whereas failure teaches you lots of things. For one, practically speaking, failure helps you to figure out what you’re doing wrong. Also, I think with failure comes a degree of humility. What I learned from success is that — and this is such a clichéd answer — but everybody on the planet desperately pursues success without any sort of empirical awareness that success tends to make people miserable. I mean look at every rock star who’s had a lot of success: they’re either a dick or they’re dead. Think of who Kurt Cobain would be if Nevermind had just been a hundred thousand selling indie rock record. Think of who John Lennon would be right now — probably a granddad with his grandkids — if he hadn’t been an iconic rock star. Success has rarely done people any favours in terms of lifespan or quality of life.

We live in a culture where people expend so much energy trying to present themselves as people they aren’t. I get really tired of that.

Have you found success to be very fleeting?

Depends what utility the success has in your life. There’s the practical side — it enables you to simply take your friends out for dinner and buy nicer Christmas presents for your family. It’s also nice to have an audience for your work. But all the other stuff is really pernicious and unhealthy. Let’s use Madonna as an example: if she puts out a record, she really desperately wants people to love her for it. But it’s so weird how — and I’ve done this as well — your perception of self is influenced and affected by people you’ll never meet. It’s kind of insane, you know, to read a review and have it ruin your day. Why would I let the opinions of complete strangers affect or compromise my emotional state? Then success wanes and you find yourself being invited to fewer parties and you start to get depressed until you realize you never had fun at those parties anyway.

In the 2000s, it seemed I was hearing Play in just about every other commercial or movie. [4] Some would call you the original sellout. What’s your response?

Well, there are a few different ways of looking at it. I’ve always found it very ironic that journalists who’ve accused me of being a sellout usually were writing for magazines wholly supported by advertising revenue. [5] And then you can look at it more broadly: if you are offended by consumer products, why are you wearing sneakers, jeans, a T-shirt, and driving a car? There’s a quote from Jeff Tweedy that I really like, back when he got criticized for using a song in an ad. He simply said to these people, “20 years from now, when I’m not selling records anymore and need to pay for dialysis treatments for my child, where are you going to be?” Also, to be honest with you, it’s become a complete non-issue because every musician on the planet is bending over backward to license his or her music now. And the majority of journalists who criticize people for licensing their music, they’re all unemployed.

Where does Moby fit into the musical landscape of 2016?

Oh boy. [Laughs.] I think it depends on who you ask, how old they are, and where they live. If you ask a 12-year-old, my place in the musical landscape is that I had a cameo on Bob’s Burgers. Or maybe they might be vaguely aware of me as the guy Eminem dressed up as. But if you talk to, like, a 40-year-old in Canada, maybe I’m the guy they saw at their first rave, or the person who made the album that they had sex to in college. So I don’t know how to answer that. Releasing an album in 2016 is like being a self-published poet: you don’t really expect anyone to pay attention and you certainly don’t expect to make money from it. I’m putting out a new record in September. I love making records, but I don’t really expect anyone to notice. If, by some fluke, someone listens to it or buys a copy, that’s fine, but that’s not really the goal.

Since you brought him up, and we’ve been talking about haters and criticism, I’ve got to ask: after all these years, have you finally made amends with Eminem?

No. I mean, I think in 2002, when he rapped about me in that song, we were relative professional peers. But since then, he’s gone on to sell a hundred billion records and I’ve gone on to do other things with a lot less commercial success. So I doubt I’m even on his radar at all. But also, he’s kind of an interesting example: you’d be hard-pressed to find a solo musician who’s had more success than Eminem. At this point, he’s probably sold over 100 million records. [6] But whenever I see an interview with him, he just seems really unhappy. So, it just sort of begs the question: what’s the benefit of having obscene amounts of success if it doesn’t actually improve the quality of your life and you can’t do anything good with it?

I guess leaving behind a legacy is overrated.

Oh, especially a legacy in a universe that’s 15 billion years old. I mean, at best, a legacy lasts 100 years. And 100 years compared to the age and scope of the universe? That actually doesn’t even exist.

•••

[1] Moby is a distant relative of Herman Melville, the guy who wrote Moby- Dick. Get it?

[2] Among the women Moby’s romanced: Natalie Portman and (Mike Myers’ current wife) Kelly Tisdale.

[3] In 1996, Moby released Animal Rights, a guitar-fuelled attempt at winning over alt-rock crowds. It flopped so monstrously he considered quitting music and going back to school. It has yet to enjoy a critical re-appraisal.

[4] The song “Porcelain” alone was used in the soundtrack for The Beach and ads for Volkswagen, Polo, Bosch, and France Telecom.

[5] Yes, that is Moby throwing shade at us.

[6] Indeed, Eminem has sold over 172 million albums worldwide, making him the best-selling hip-hop artist of all time. Moby, in comparison, has sold 20 million albums, which is still more than we’ve sold.