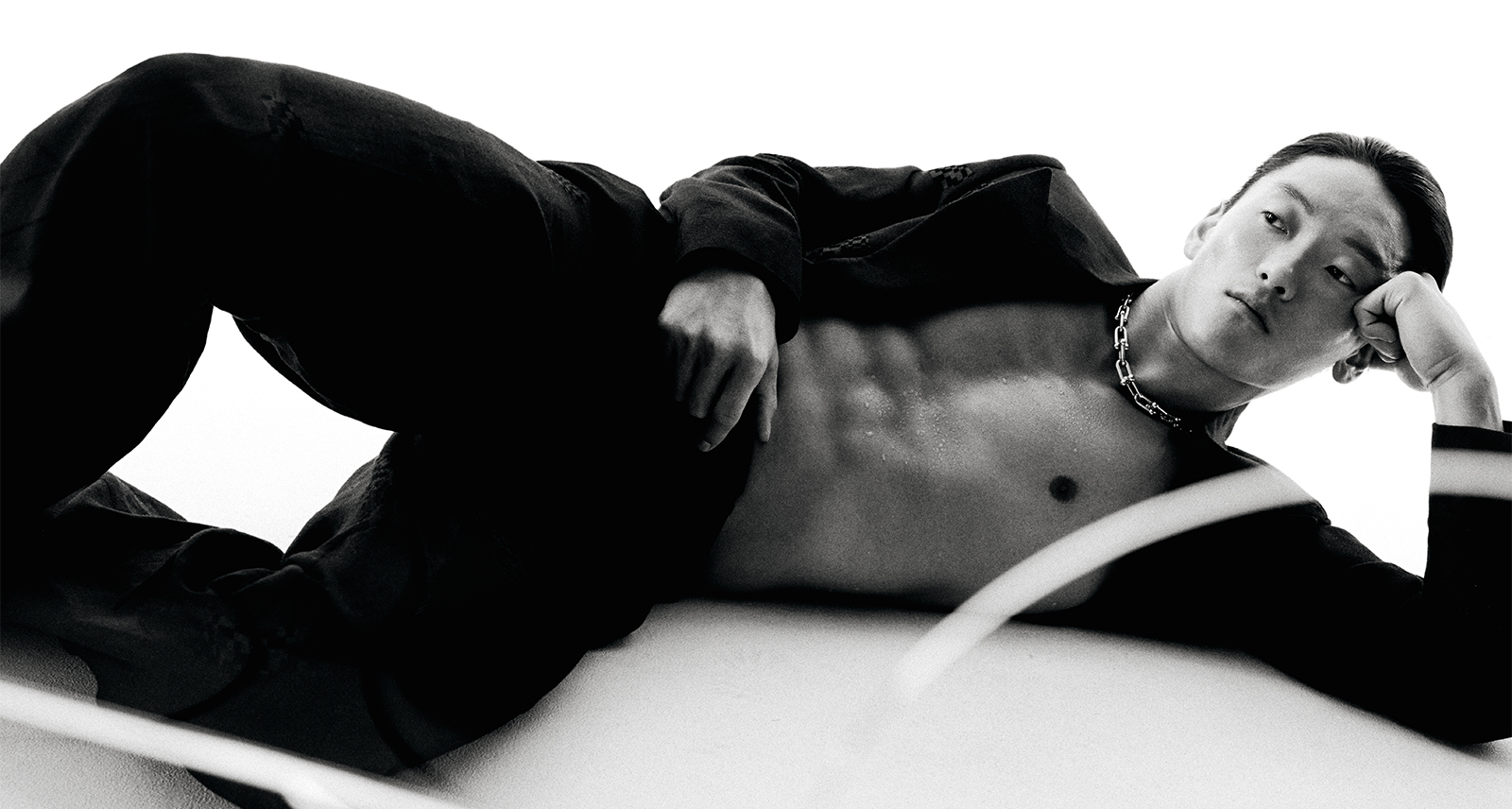

Michael Chabon Is Lying to Us

There’s never been a better time to write a fictional memoir. Just look at Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle series, or Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. Both are richly specific personal stories that, while categorized as fiction, likely contain more real-life experiences than The Art of the Deal.

As our tenuous hold on The Truth wanes in real life, we seem to be yearning for fact-checkable realism in our fiction, even if it’s clearly labeled as fiction. It makes the work feel more important, more honest. There’s something about overt ambiguity — true stories, but with the emphasis on stories — that people instinctively understand. Maybe it’s because we’re all familiar with how our own memories work. Or maybe it’s because we never assume anyone is ever telling us the full truth anyway. Either way, the truer-ish, the better.

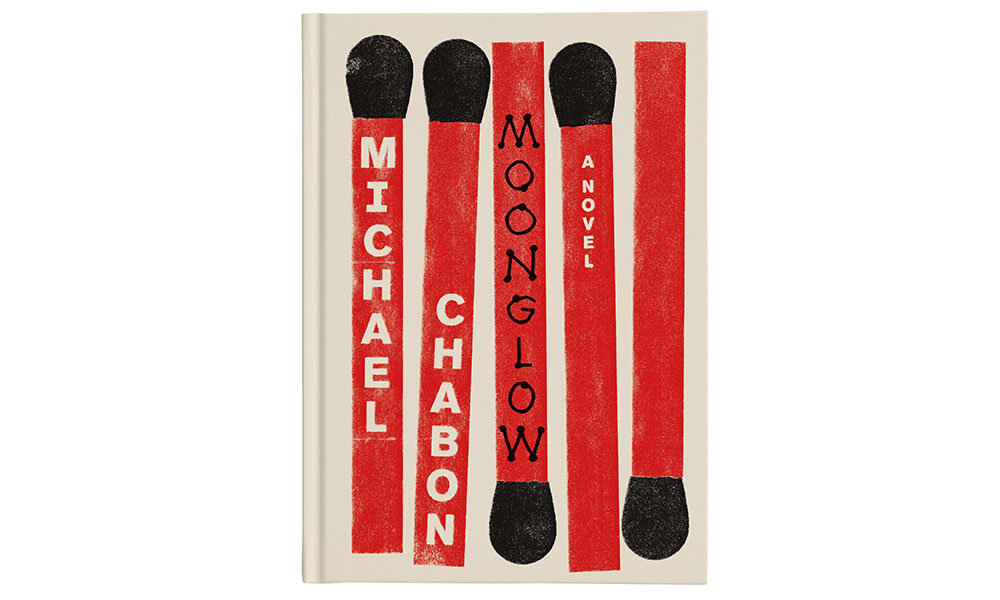

Michael Chabon’s latest novel is a warm and inviting home that’s been built in that liminal space between fact and fiction. According to the novel, when Chabon was in his twenties he sat with his mother’s father, and heard the full details of his family’s history before his grandfather died. Moonglow is an adventure story pulled together from those memories: his grandfather’s time searching for Nazi scientists in World War II, his marriage to a troubled French refugee, his stint in prison, his career as a model rocket tycoon, his late-life romance. It’s a full, complex, sad, and beautiful life. Only, it’s all a lie. Not that it matters.

It’s nearly impossible when reading not to wonder at the similarities between the work and the writer; to speculate on what is true, and what has been wholly imagined. It’s a trap, of course, unfair to the novelist and mostly impossible anyway. But even before Moonglow, Chabon blurred that line. His first novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, seemed like it must be about its author, who graduated from the same school as its protagonist and vaguely fit his description, too. Then, after the success of his first novel, Chabon couldn’t finish his second: as the page count rose precipitously, he couldn’t bring it all together. In the end, he threw it out, and instead wrote Wonder Boys, a comic novel that happened to be about a writer who couldn’t find a way to end a sprawling work. The parallels are obvious.

Chabon plays with this in Moonglow. Throughout the false memoir, he sprinkles in details that could easily have inspired bits and characters in his earlier works. His “father” gets embroiled in money laundering, which — gosh — seems to mirror the gangster patriarch in The Mysteries of Pittsburgh. It’s fiction within fiction, and it feels a bit like a game. Which is to say, it’s fun to read.

“I miss being able to easily pass things off, in a way — not because I’m trying to deceive the reader, because the reader is asking to be deceived — but to put us both in that magical zone between belief and disbelief, between fact and fiction,” he says. “Part of the fictional game of this is to say: this really is my memoir. The reason you can tell this is really my memoir and this is really my grandfather is because if you’ve read all my books you’re going to see where I get all this stuff I write in my books.”

All this would be infuriating if the magical zone Chabon pulls the reader into wasn’t worth spending time in. And Chabon is, still, a dazzling storyteller — enthralling in both form and function. His sentences are intricate and surprising; they make you feel at once at home, and in an entirely new world. He’s funny — the kind of funny we don’t often experience: rueful, nostalgic, smart. The end result is deeply generous and humane, full of life and moments of honest-to-god truth.

“Fictional truth is much more valuable, useful, and openly truer to me than supposed non-fictional truth,” Chabon says. “The best memoirs, the ones that mean the most to me, are the ones that impose pattern on life.”

A true story isn’t necessarily more compelling just because it really happened, nor is a story any less true just because it happens to be fiction. So, yeah, Chabon is lying to us. But we’re going to lie to ourselves anyway — he’s just much, much better at it.