Everyone Is Freaking Out Over George Saunders’ First Novel

Read enough of any one author’s work, and you’re likely to discover their pet obsessions. John Irving has a thing about bears. Michael Chabon can’t seem to help writing about tragedies befalling dogs. For George Saunders, it’s ghosts.

His four books of short stories are full of spirits popping up or hanging around. It’s not about horror — he just likes them. Or, rather, he likes what ghosts mean — what they say about time, or guilt, or our inability to get over ourselves. “We’re just these Darwinian cut-outs,” he says. “But ghosts are a rudimentary way of reminding myself that what we see can’t be the end all and be all. We’re literally just perceiving machines with a very narrow focus.”

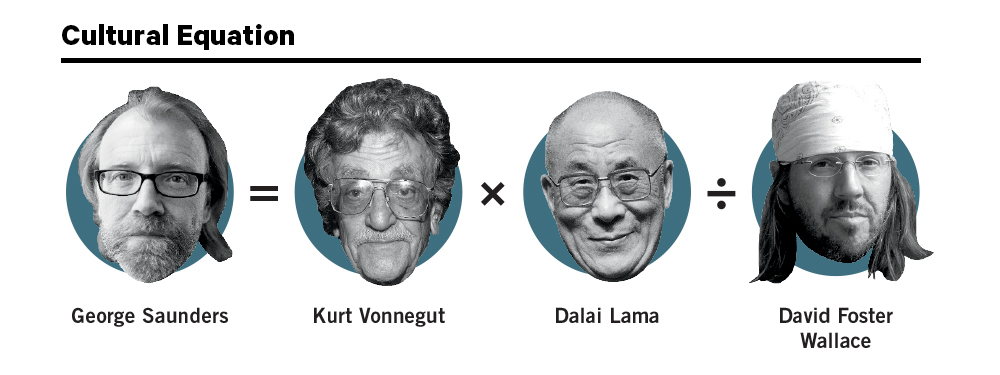

Saunders is all about expanding our focus. He’s doing it now by publishing his first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, at age 58, after a long career of writing short and non-fiction (which has given him accolades such as the prestigious MacArthur Genius Grant). The book traces the story of what happens to Abraham Lincoln’s son, Willie, after he dies. (For those unfamiliar with Tibetan Buddhist doctrine, the Bardo is like a purgatory, in between life and death). The story is pure Saunders: heartbreaking, humane, deeply generous, weird, and, not for nothing, funny. Imagine Kurt Vonnegut — all his humour and humanism — and inject a healthy dose of both the spiritual and the surreal, and that’s Saunders. He deserves to be your next favourite writer. Sorry, novelist. He’s a novelist now.

Your first book was published 20 years ago. How has the work changed since then?

I just read a thing about the detriments of multitasking. And I can feel it. My reading retention isn’t what it used to be. I’m thinking of doing some blockading now. Because I’m very obsessive about emails and my phone and stuff; when I first started with it I could feel myself getting dumber.

But you could probably stand to get a bit dumber.

Maybe. I’m also getting older. Older plus dumber is kind of a bad thing. You can see on the one hand the neuron firings are a bit slower, but it feels like the experience of life makes you more of an efficient thinker. Like you’re not spending as much time with your thoughts all over the barnyard.

But I can tell I don’t have the explosive verbal capacity. I used to turn my mind in a certain direction and it would just [explosion noise] and this monologue would appear. And that doesn’t happen. Although, those were often shitty. At least now, at 58, there’s kind of a trade off. I’m not quite as explosive, but I’m a little more disciplined.

When I found out you were writing a novel, part of me assumed it would be different from your regular writing. I was imagining a sprawling family epic. But it’s still very much a George Saunders thing.

I had the same progression that you described. I’m going to write a novel, and it’s going to be so different, and I can’t wait for the difference to start. The joke I make is that I’ve been making custom yurts my whole life, and somebody said, “Can you build a mansion?” and I said, “No. Wait! Yeah! I can just combine a few yurts.” I fought so hard not to write a novel, that when I got into it, I did it begrudgingly. I tried to keep it honest. Abide by the same principles as a story, which is if you’re central, you’re welcome, if you’re not I’d like you to step out. I still had the idea of the sprawling family epic, but when I would think of it I would almost throw up.

Why is that?

You know what it actually is? When you say “sprawling family epic” we both know what that book is. And who wants to write that book? If we can imagine it intact, why do we want to write it?

So the thrill of this was to say, “If you insist on being written after these many years of thinking about it, I’ll do it. But please don’t tempt me down the path of banality. Let me not phone you in.” Surprise me, in other words. And it did.

“As you squash your projections, something else rises up in place of that. I would say it’s love, basically. Small liberations are possible.”

Why Lincoln? Was it important to have the story be about him?

It wasn’t. I heard that story years ago, about him holding the body of his son, and I never forgot it. I would often think about it, but then I would think, “Fuck that, no way, it’s too hard, it’s too earnest. I can’t do it.” It was something annoying about the fact that at my age, and at this stage in my career, I was shying away from something because it was too heartbreaking or earnest. It wasn’t so much Lincoln, but it was that particular story. Gosh, I didn’t want to write about Lincoln. That’s like writing about Ghandi.

One thing as I’m getting older, you realize how long a human life is, how difficult and how limited. And you see what Lincoln did in those four years, how much he grew. I think he was an incredible spiritual being of some kind. He went from being racist in the way most people of his time were racist. But in those three or five years, you can mark places where he somehow just jumped several generations ahead, and turned around to lead the country. It’s weird when you think how short of a time it was between conventional Lincoln and God-like Lincoln. It’s one of the most exciting transformation stories.

That reminds me: in a recent New Yorker piece about Donald Trump supporters, you wrote about two Americas. Do you think people can ever actually change their minds, when every fact can be taken from both sides to mean exactly what you want it to mean?

I think the media and the Internet make it really hard, because there is that echo chamber. But the only thing I can figure is that it has to do with paradigm shifting. One of the difficulties now is that the paradigm is so strong. It’s so rigid. But take Lincoln. He was an incredibly logical thinker. He was drawn to specifics. And as a fiction writer there is something to that. In other words, when I write something in a first draft, it’s usually shit. It’s hyperbolic, a little vague, blurry, self-reinforcing. All of these things. The process of revising is a way of getting in touch with specificity and detail. Thereby outing your own bullshit and lazy thinking. In my artistic life, I’ve been made a better person by the way in which fiction forces you to deal with specifics.

Your work seems to reflect your belief in life after death. The singular becoming bigger and bigger until it encompasses everything…

I do believe that. In the actual Tibetan teaching of the Bardo, most of us just miss it. But I think it’s true right this minute, too. What I mean is this: you’re sitting there, I’m sitting here. On a molecular level there’s just molecules, molecules, molecules. There’s no difference. What makes us separate is consciousness. I come alive and I go “I’m George. I’m the best,” or “I’m the worst. I’m at the centre.” If you didn’t have this mind that was constantly telling you how separate you are — but that’s a trick of perception. The only reason we think we’re separate is we have this little thinking machine that, for Darwinian purposes, tells us to, say, run away from that bear, because you’re separate from that bear. And I think that at the end of your life you re-join that.

In other words the self and all the things that make it recede. In the stories, it’s a reference to those things. I think it’s true now, and I have a feeling that it will be true at the end. But who knows.

It seems like that’s a guiding principle — a lot of your stories touch on the idea of getting out of yourself.

We’re constantly projecting — it’s what we do. But through certain spiritual practices, and also through writing, we can realize, “Oh that’s a projection; I actually don’t know that person.” In grand and banal ways, that’s what we’re here to do. And my feeling is that as you squash your projections, something else rises up in place of that. I would say it’s love, basically. Small liberations are possible.

Putting aside spirituality or religion, that’s what we’re always dealing with. We’re telling ourselves the story of our perception, over and over again.

I think that’s absolutely right. And there are better stories and there are worse stories. That’s kind of what meditation is — you’re just watching the stories you’re telling yourself at any given moment. I can remember, as a little kid, thinking I wanted to be famous. I wanted to be great, beloved, and I think now what I feel is if thinking a certain way gives you energy, then god bless it. If you were hungry and it was inconvenient to be hungry, and you say you’re not hungry, you’re just lying. To be in line with the truth is energizing. So my feeling is, if I have an energy of ambition, which I certainly do, then I’m going to treat it like a game and just indulge it. But, at the same time, the responsibility is to not believe in it as anything other than an energy. It’s not true. It’s not real.

I think I’m always asking the same question: I think the world is shitty, but you’re one of my favourite authors and you seem to have…

But, why do you think the world is shitty?

I mean, putting aside all the horrible things that don’t really happen in our part of the world, I think the world is full of people who want to be known and special. But that’s impossible. We’re all mostly average and mostly anonymous, and that can be so sad.

I think life can be shitty, but we know from experience it isn’t always shitty. My aspiration, which is impossible, would be to know all the way the world can be simultaneously, and this book kind of underscores it. The world is no one way, except in one’s head. The world is molecules. I think the ultimate view would be to be able to affirm every consciousness as equally valid. What a beautiful thing that is. That every misconception, every perversion, it just is. But I don’t feel like the world is sad. It’s everything. There are days I wake up and think I’m the worst person in the world. Then sometimes I can step outside and say, that’s your mind. Just your mind. I am starting to feel almost more generous about people’s basic natures.

I think most people are incredibly kind. They default to that.

I have that same thing though. If I have a friend that’s down, I have no prob- lem helping them see the positive. But when it’s in my own life…

I know just what you mean, and I struggle with that a lot. Sometimes I would have certain insights, where I would do something I regret — I hold myself to a higher standard as I get older, and I disappoint myself more and more. But then I think the reason I’m feeling that way is that I’m clinging to myself as a permanent, central, enduring, important entity. And that goes against the Buddhist teachings. As I get older, I’m trying to think of myself as just another collection of stuff, which of course is going to make mistakes. And if you make mistakes, I’m going to be merciful to you because of course you’re cause and effect, your whole life led up to this moment, you made a mistake, it’s going to keep going, but we see ourselves as not being in that flow.

Now that you’re officially a novelist do you feel you have a different responsibility?

Not relative to being a short story writer, because it’s the same. I find myself thinking about why written fiction is important. Or whether it’s important or not. Because if it’s unimportant, I’m wasting my life.

I actually am more sure now that it is, because what I think it does is everything we’ve talked about. If I’m trying to connect with you as a human being, what’s the best way to do it? Well, talk. But I don’t feel like I’m my best self while talking. My anxieties are on the surface, my insufficiencies of thought are at the surface. But if you give me a while to sit down and write you something, I think I’m my best self when I’m doing it, and I also think I’m my best self when I’m receiving it.

For neurological reasons, our brains do really well with text. And here I am talking about the responsibilities of the novelist, but in a way our communication has become so foreshortened, so superficial, that it’s really easy to forget that deep communication is possible. You come to think it’s all shorthand. One thing that a novel does is to remind us that we have a deeper capacity of communication. Also, when you read even the simplest book, it neurologically forces you to be marginally more compassionate. It reminds you that your mind isn’t the only mind. That is huge, and I don’t know any other art form that does it as well. And in that process, fiction reminds you that you are actually okay, that you are not alone, that it’s possible to communicate deeply with another human being. Nothing does it better. I really believe that.