Pierce Brosnan Talks ‘The Son,’ Returning to TV and What It Means to Be American

There’s a long-held theory that becoming James Bond — the most iconic of iconic blockbuster action heroes, the Dallas Cowboys quarterback of modern cinema — is actually crippling to an actor’s career. But if there’s any truth to that notion at all (Timothy Dalton, where you at? What’s really good, George Lazenby?), it certainly doesn’t apply to Pierce Brosnan.

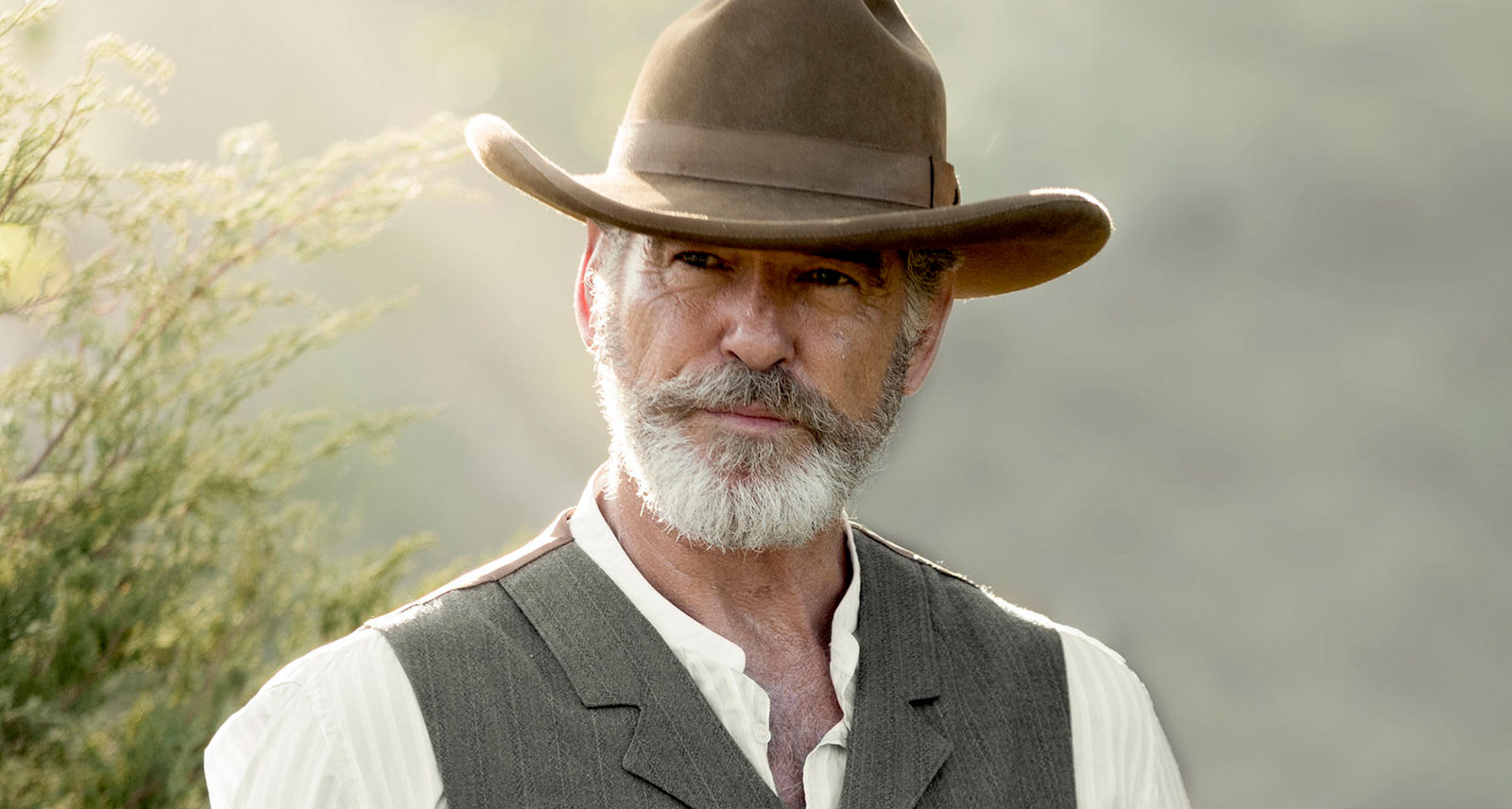

Since turning in his license to kill in 2002, Brosnan has forged a fruitful, wildly varied, admirably eccentric path. He caricatured his Former 007 status as a washed-up assassin in The Matador, belted out ABBA jams in the screen adaptation of Mamma Mia!, and had a memorable turn in the Edgar Wright action-comedy romp The World’s End. Now 63, the Irishman has returned to television for the first time in 30 years as Eli McCullough, the coldblooded Texan paterfamilias at the centre of AMC’s new generation-spanning prestige drama The Son.

We caught up with Brosnan in Toronto, shortly after arriving from the show’s premiere at the SXSW Festival in Austin, Texas.

SHARP: You premiered the first episode last night in Texas, where the show was shot and is set. How did it go?

PIERCE BROSNAN: We showed it at the Lyndon B. Johnson Library in Austin — right in the belly of the beast — to a roomful of Texas families. It was very well received. They said they liked my accent, and I took them at face value and believed them.

Was that accent the hardest part about this role for you?

That was the challenge for me in this part. The rest kind of came very easily — I know how to ride a horse, and I know a bit about weaponry and handling guns. So it was really about dealing with the accent, which I fell into immediately.

What was that process like?

I have a wonderful dialect coach, Brendan Gunn. We’ve worked a lot together. He lives in Belfast and works all the time with Daniel Day-Lewis — he’s a genius. So I started with him and immediately began to put the twang on and just went for it. There was no time to second-guess.

Was there a Texan accent that you modelled yours after? Someone in particular you looked to or listened to a lot?

I listened to a cross-section of Waylon Jennings, Rick Perry, Willie Nelson and a congressman called Ted Poe. Congressman Poe was the one that I kind of hung my hat on. He gave a very emotionally charged speech in the House last year, and I kept coming back to it to listen to the beautiful tonality of his voice.

This is your first regular television role since Remington Steele.

That’s right. It’s been awhile.

What brought you back to the medium after so much time?

I’ve been actively looking to come to TV because the beauty, variety and texture of the work being done right now is exhilarating. I’ve always considered myself a working actor, so I go where the work is. I spent the last three or four years with my producing partner trying to find the right material — something that would stick to the bones, that I’d be excited to do for three or four seasons or more. Lo and behold, it was The Son.

What was it about the material that spoke to you?

The job came out of left field, really. I knew the director, Tom Harper, because I was supposed to do Peaky Blinders, which Sam Neill wound up doing. Sam was supposed to do this, and then couldn’t, and it came to me.

It’s funny how life works sometimes.

Isn’t it? I’d read the book [Phillip Meyers’ 2013 novel The Son] when it came out, so my interest was already piqued. And then my agent sent five scripts over that weekend, and I tore through them because the writing was so good. This character, Eli McCullough, I just found him so fascinating.

Most viewers are used to seeing you with a cool, collected air onscreen — whether it’s in Bond or The Matador or The Thomas Crown Affair. But on The Son, Eli has such a darkness about him — there’s a real unfettered rage boiling under the surface. Was it a fun change for you to explore that anger?

I love his rage. I love his medieval, bacchanalian savagery. He’s born of violence. He’s a man whose life was mangled at a very early age. By the time we see him, he’s already lost three families. He’s Comanche chief and he’s white man. There’s a duality there, a complexity to how he sees the world. He knows both sides and he does his best to try and control it.

When you’re playing a character like this — who can be fairly brutal at times — you have to walk a line where you don’t want to push the audience away. You want to creative ambivalence. That’s the fun of playing him. When you have ambivalence, then you have conflict and drama and that makes the audience love and hate him, be fascinated by him and the audacity of his ways.

Were westerns important to you growing up?

The movies were very important to me, and westerns — along with British comedies — were very much the staple diet of young Irish lads. There were two cinemas in town — one at the top and one at the bottom. I always went to the one at the bottom; it was the closest one to the house.

I always wanted to be a cowboy, but when I was a kid, I always played the Indian. I lived with my grandmother, and she had these old tinkers — traveling people — who came around every springtime to live on her land. They had two sons and we’d go off into the forest, and they’d show me the best wood to build bows and arrows and how to make them properly. Those are the things — in the innocence and twilight of youth — that stay with you.

And yet, what’s interesting is that while I strap a gun on my hip everyday in this role, I actually don’t see it as a classic western.

What is it to you, then?

It’s a drama, a saga, a family dynasty. It’s Shakespearean and Jacobean in tonality. Eli wears a cowboy hat, he’s a rancher, but I don’t think you can just say it’s a western because you go through the book and it’s about so much more. It encompasses the birth of a nation, the brutalization of one community against another, and the constant conflict that still remains in our society today. It’s about land — it’s always about the land. Having land myself and living beside people, you see it. It brings out in people a real possessive, angry quality over boundaries.

The Son is, in part, about identity and what it means to be American, which is a rather hot-button topic at the moment. You’ve been a U.S. citizen for well over a decade at this point. What does being American mean to you?

Freedom of speech. Being good to the people around you. Being openhearted and hard working. Passionate about the possibilities of life, about making the world a better place and doing good things within it.

I love being in America. When I arrived in America 31 years ago, in 1986, I felt lucky. I was lucky. I felt accepted and that anything was possible. I have American sons. Even through this turbulent, crazy time, good things will come from it. There’s such a disconnect and a real pain in the country — it’s so torn apart and divided. But in these times you have to adhere to the goodness of life, I believe. You always have to go to the higher ground. You have to have humour about it, you have to have grace under pressure.

This is a really fertile creative period for you. I took a look at your IMDb page on my way over here, and you have 5 or 6 projects either in post- or pre-production. Having accomplished all that you have in your career, what continues to drive you forward?

I like to work, I want to work, and I have to work — I have a family and I have overheads. Essentially, I just love being an actor and I feel alive doing it. Nothing comes from nothing — it’s all about doing. So that’s what I do. This is my job. This is my life. They pay me, I travel and it’s magic. I’ve never worked a day in my life.