Author and Explorer James Raffan on His Book ‘Ice Walker’, Polar Bears and Hope When It’s Hard to Come By

Coca-Cola first used a polar bear to sell its product in 1922, with a French print ad that illustrated a smiling bear sharing the beverage with an equally happy sun. In the decades since, polar bears have been used to sell everything, from ice-cream bars to hygiene products. But today, polar bears are the most visible victim of the climate crisis, the impacts of which are being felt most severely in the Arctic. As temperatures rise, sea ice dwindles, and the fate of polar bears – creatures of the ice – has been thrust into jeopardy.

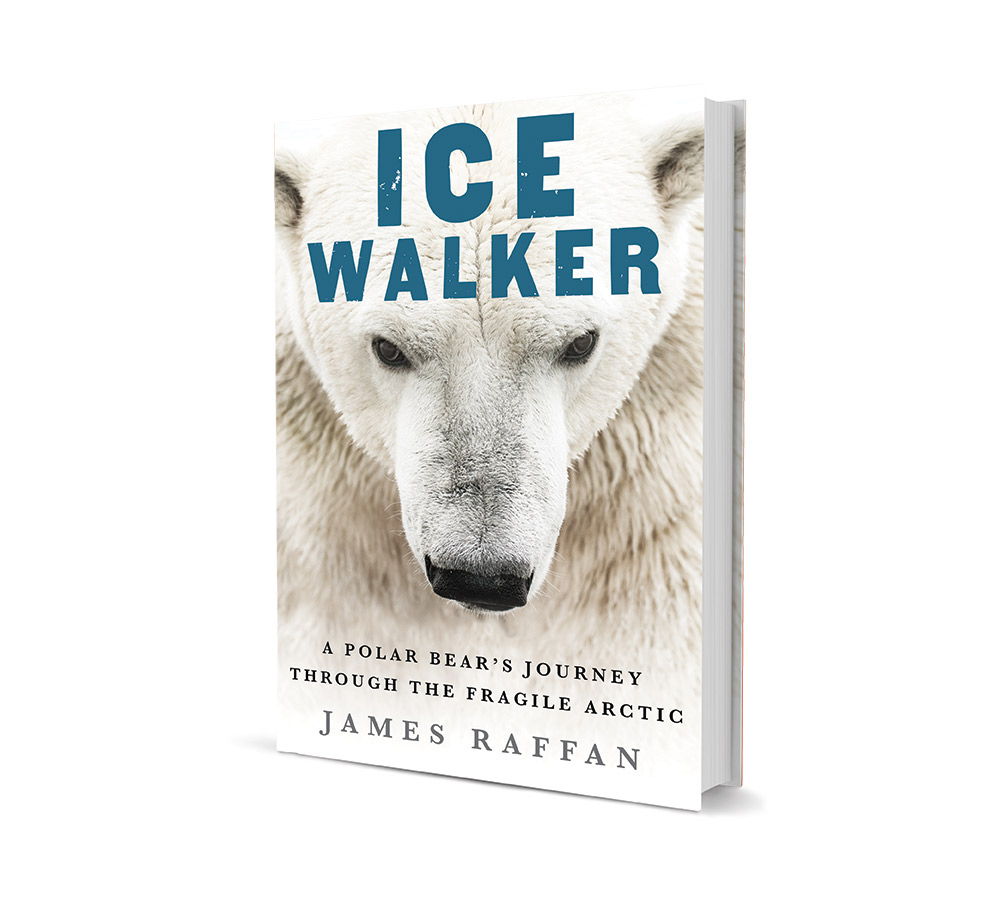

After more than 40 years spent living and travelling in the Arctic, Canadian author and explorer James Raffan has penned Ice Walker: A Polar Bear’s Journey Through the Fragile Arctic. Written over a span of 4.5-years, Ice Walker is a portrait of Nanurjuk, a seven-year-old polar bear in a fast-changing world. Raffan spoke to Sharp about polar bears, storytelling and hope, when it seems hard to come by.

When did you first become interested in polar bears?

Like any human with a pulse, I’m drawn to them for the reason that they’re big and beautiful. But my connection to polar bears goes back to [university]. I studied biology and, as a 22-year-old, I ended up in a lab-research facility at the University of Guelph with a big male polar bear, teaching it to press paddles to a light stimulus. What I realized, sitting in this room which was often dark because [we were] learning what the bear [could] see, was that it was slowly going berserk. And I left. I walked away from that research project; away from the bedrock of science towards the people who took me to the bears in the first place, who were the Inuit in Churchill, Manitoba and up the west-coast of Hudson Bay. That has led to a lifetime of travel and learning from people around the circumpolar world, all of whom are connected, in one way or another, to bears. [My] first impulse to write Ice Walker was my debt to that bear at the University of Guelph. His name was Huxley.

Do you think that telling the story of a polar bear’s life is more likely to incite human behavioural change than just reciting facts or stats ever could?

I’m betting on that, but the jury is out. If you look at what drives our behaviour, we don’t act on what we know. We act on what we feel. And interestingly, I know a lot of natural history about bears having started as a scientist and I have learned a lot more [since]. In the early drafts of Ice Walker, I wanted to put as much of that in as possible to help the reader become aware of the amazing characteristics of bears. I think one of the reasons why [the book] took 4.5-years to come to life was that I was in the business of chopping a lot of that stuff out of there to leave the story, which is about a mother and cubs and that primal instinct to provide the best for the next generation.

While Ice Walker explores the uncertain future of both polar bears and humans, were you able to find hope while writing?

Bears are in a very precarious place. [And] what I argue in the book, eventually, is that we are the bear. The Arctic is a long way away but in terms of the processes that affect our lives, the Arctic and Yonge-and-Bloor are effectively connected. [But] I believe hope is a choice. I really do. There is hope in picking up a book like this. There’s hope, for me, in small changes that you might make in your life: travelling less, eating lower down on the food-chain, choosing to buy less knowing that they’re going to reduce your impact in the big picture. For me, writing Ice Walker was in some ways an act of hope. For the entire writing period, I did nothing, really, other than think about the relationship between people and the earth intensively. A lot of days, despite the gloom and doom of the situation, the act of engaging [with it] put a spring in my step.