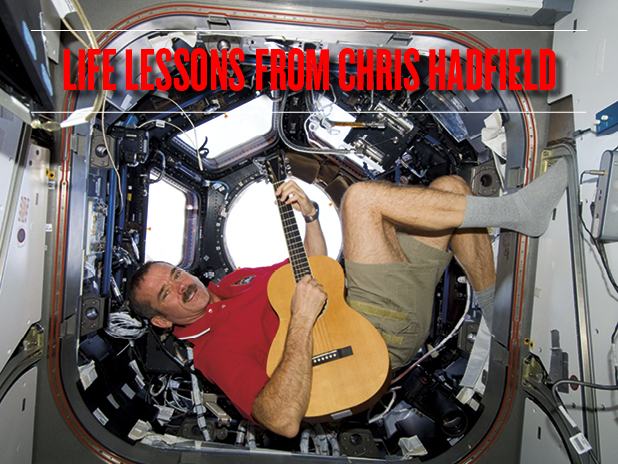

Life Lessons from Chris Hadfield

Offhand, your average guy can name probably three or four astronauts. That’s not including Han Solo or crew members of the USS Enterprise. But you can bet that Chris Hadfield’s name is on that list. After commanding the International Space Station last year (and singing David Bowie’s Space Oddity from space), there are very few Canadians who haven’t heard of Hadfield.

For a sparkling moment, Hadfield made all things space cool again, and he did it without Han Solo’s swagger or Buzz Aldrin’s machismo. He did it humbly. And, talking to him, you feel that genuine humility. He’s not self-deprecating or falsely modest. He has the honest humility of someone who knows their achievements, and the exact amount of work that went into reaching them; who knows the balance of fortune and effort and responsibility.

Hadfield continues his mission of simultaneously uniting humanity and getting us excited about space with a new book, You Are Here (Random House Canada, $30), a collection his photographs of the planet from the space station.

Maybe this is overly pessimistic, but when I’ve reached a goal, my life afterward can seem a little meaningless. Is that how you’re feeling now?

I think it’s all about visualizing an end game. What is your own particular personal measure of success? What is your definition of having achieved what you’re trying to achieve? I think it’s really important because my goal in life was not to command the International Space Station. I decided to be an astronaut when I was 9 years old. It was a deliberate decision, I was about to turn 10 and that’s when they walked on the moon. It was the summer of ’69, I decided that night. ‘I want to do that, that’s the coolest thing ever. How do I do that?’ So I set that that goal, recognizing that there’s no way that’s ever going to happen.

I did realize that the only way that it for sure was not going to happen was to not try. The other side of that was that the only thing I could really modify was myself. I can’t really modify the world space program or world politics or events or shuttle explosions. So I gave myself this distant, unachievable goal and said, “Okay, if everything goes perfectly that’s going to happen.” Things aren’t going to go perfectly, but if every little tumbler in life just clicks into place at just the right moment, then eventually I will walk on the moon. That’s my definition of perfection, but life is what’s really going to happen.

Now I know where I’m headed, let’s do something that moves everything in that direction. It gave me an idea of what to do next. Your life is nothing but next decisions, right? Do you want water or do you want Diet Pepsi? What are you going to drink next, what are you going to do next? The real key to that is, I never once said to myself, “If I don’t get to walk on the moon, I’m a failure.” It was never my definition of personal success, it was just a long term possible destination. But, for me, no matter what happens, I’m dragging or pushing in a direction that naturally suits and interests me. Every step I take, every choice I’m making, moves my life in a direction that I like better. And celebrate the fact that, hey, you know, someday I want to walk on the moon but this week I learned how a wing works. I learned how an airplane actually leaves the ground. Or I learned orbital mechanics. Every single week I’d go, “I’m not walking on the moon yet, but I just did some stuff that’s really cool.”

The breadth and depth of the measures of my own success were huge. I got to live at the bottom of the ocean for a while and I got to intercept soviet bombers off the coast of Canada and yesterday I flew with the Snowbirds over Parliament Hill. All of those things were part and parcel of having that long-term goal in mind. You have to celebrate and enjoy what is actually happening and love what’s happening and admit to yourself that your end game might never happen. I still haven’t walked on the moon, and I probably won’t. So by definition, I’m a failure. But I’ve really liked everything I’ve done. And I really like what I’m doing now. And I still might walk on the moon.

When you do see something as beautiful as the view of planet earth from the station, does that put a damper on a sunset here at home?

Not at all. I mean, just because you’ve eaten truffles, doesn’t mean you hate all the rest of the food in your life. It’s just “Hey, I really like what I’m eating right now, and I like truffles.’ You could either view it as limiting or defining or as enriching. It’s like, I speak English and I learned to speak Russian. So does that mean that all the other languages suck? No. Or all other languages don’t matter? Or I’ll never appreciate another language? No. The fact that I speak Russian is enabling, it’s helpful, it gives me a little more of a platform to try to understand the world.

Did you always have that sort of positivity?

Yeah I think so. I grew up on a farm. And you work hard and get stuff done. The stuff you know allows you to better appreciate the stuff that is coming. Be better prepared for it and maybe get more out of it.

If for some reason you hadn’t been able to achieve your goal, would you have been discouraged? It doesn’t sound like it.

No. I was a downhill ski instructor and I loved that. I’d happily be a downhill ski instructor for the rest of my life. That’s a great job. I was also a farmer, working for my dad. I was an engineer, I was a fighter pilot, I flew CF 18’s. That was really interesting work. And then I was a test pilot, and I loved being a test pilot because it’s engineering…

And badass.

And a complex mental challenge. And managing risk and danger, and having a purpose to it. We redesigned the controls on the F18 so that they stopped crashing and I tested a hydrogen burning engine on the wing-tip of an F-18 that would hopefully allow hypersonic flight. It’s interesting work that accomplishes something. And the only other job I would have wanted to do was get hired as an astronaut, and luckily I did. But I would have been very interested to continue what I was doing. The real key is to not to measure your life by the few high points. Because otherwise everything else looks like a low point. And the key is not to define yourself as a success or a failure or by things you can’t control that might happen in the future. Otherwise you’re just setting yourself up for disaster. Imagine the Olympians that went to Sochi this year had said ‘if I don’t win a gold then none of this was worth it.’

I think that some of them did.

I know, but then you are guarantying yourself a horrific psychological problem.

I’m an anti-bucket list guy. I don’t like bucket lists. That means that for almost your entire life you’re carrying around visual evidence of your own failure. Why do you do that to yourself? Every morning you can say “God, look at this, it’s a gorgeous day today. The sun is shining in my bedroom, and I had Cheerios for breakfast and I love Cheerios.” I’m not some sort of idiot. You can deliberately choose to have a full bucket every night before you go to bed.

Is there a difference between what you’re describing and dumb optimism like “everything will work out no matter what”?

Yeah, visualizing success to me is a waste of time.

Really?

I visualize failure all the time. Because things are going to go wrong. I want to walk on the moon but I’m sure not going to walk on the moon if all I think about is wishing it. I want to walk on the moon so what’s liable to stop me from doing that and let’s start working on those things.

There have been astronauts for 50 years and yet the things that people are the most curious about seem to be the most benign. Does it surprise you that it’s the simplest things that we still want to know about?

No. It’s new to the human experience and, up until now, it’s been really hard to share. And to separate a science fiction movie from the reality of what we’ve been doing. Now it’s almost as if we’ve let everyone in. We have the technology, the ability to communicate in real-time. When they look up and they see the space station go over it’s not just some little beeping sputnik. They’re in that thing. And that is going around our planet and it changes their global image, I think. And if you can get people to rethink their position on the world then it’s really contagious.

There’s sort of the understanding that we are all part of the same planet…

Yeah. I flew in space three times and of course this last time was the longest so it gave me more time to think about it. Along that vein, the first part of this is tripe but the second half maybe isn’t. When you first get up there, you see what’s familiar to you, and you see what you want to see, and what you typically see is places you’ve been . You grab other astronauts and say, “Hey, that’s where I’m from” or “Hey, that’s Moose Jaw right there, that’s where I learned to fly. Look, look!” and that goes on for a couple days and then you stop doing it because you realize it’s a little pipsqueak of a place compared to what else you can see.

I remember one day I was sitting and looking at Winnipeg. Winnipeg is kind of classic. It has a dense downtown and you can see the water that comes in and the water that diverges and the highways coming across, and the railways coming across, and the airport, and the surrounding suburbs and you can see the surrounding farms. It’s a classic human settlement pattern. And then you wait 20 minutes and you’re over some place in Africa that is exactly the same. There’s the downtown, and the water diversion, and the suburbs, and the transportation methods, and the airport and the surrounding farms. And then you wait another 20 minutes and you’re somewhere else and you realize we are in this together and those people, I know Winnipeg well, I know the people that are there, I know what it’s like. And then I see some city in eastern Africa that I don’t even know the name of, but it’s exactly the same. And it gives you the recognition that I know what people in Winnipeg want out of life. They want a little grace and something good for their kids, and they want to have some fun, and they want to be productive, and they want their kid to have the opportunities that they didn’t have. They’re just people. When you go around the world as many times as I have, the sense of ‘them’ diminishes and disappears and it’s all just ‘us’. And I didn’t do that on purpose at all but I found that when I was writing tweets everyday that somewhere along the line I started referring to it all as us and not “look where the Pakistanis live here in Karachi” or “look where the Australians live here in Melbourne.” After a while I said, “look where 1.2 million of us live,” “look how 4 million of us are dealing with the problems of life” and us started becoming all-pervasive in my thinking. And it’s not like I became some sort of different person, it just shifted the distance between us off and into nothingness. I’ve been around the world 2,597 times. You can’t help but shift your perception of what’s forward and what’s yourself. And everywhere there are a few bad people, but when you see that same repeated pattern of human habitation everywhere around the world, it’s just a slap in the face reminder that we’re all in this together.

So, bringing that down to the everyday, how does that affect you? Does that change the way that you vote, for instance?

I think it makes me more patient. Because you, you know when you walk into a daycare with all those kids and all that noise and they’re hitting each other with sticks and you kind of go ‘what the hell, they’re little, they’re learning, they’ll figure it out’. You sort of feel that way about the world. That behaviour doesn’t work, but it’s human and it’s part of just who we are and it’s going to happen. You recognize that this is just us. This is how we behave. And so when I say patient, it just gives you this big, overall perspective. I’m not sure it changes how I vote but it makes me want to ask the candidates perhaps a different question like ‘what are your longterm plans for this?’ I don’t care that you’re trying to get re-elected, where do you think the country should be in ten years? What policies are you going to enable in order to get a national energy policy that makes sense? We can’t just stop producing oil or a billion people are going to starve. We can’t just undo reality, we have to find a way out of where we are and that’s why we have elected officials and people who are running companies because we’re counting on these smart, capable, empowered people to make decisions that are good long term. The global view is really important, if you’re only thinking locally, you’re going to make bad global decisions. It changes my perspective, but it wasn’t an epiphany by any means.

Are there things that you sort of sacrificed while you pursuing your goals that you wish you could go back to now? I would imagine that you didn’t party that much when you were growing up.

No. I think the key to answering your question is the word sacrifice. If I had thought it was a sacrifice that basically, by definition, would have meant I didn’t like what I was doing. I didn’t agree with what I was doing. I was saying “I would much rather be this, but I’m doing this instead because that thing that I really wanted to do won’t take me where I wanted to go.” I very seldom did that in life. I liked what I was doing so there have been very few times I felt like I was sacrificing something. Now, if I had life to live over again, I would probably make some different choices. But there’s no control group either. And I could say “I wish I had taken ballroom dancing or I wish I spent more time with my kids” or whatever, but it’s always a guess and a balance. I coached all my kids soccer teams and went to all their swim lessons, and I took them all on trips every year and they came with me and I did homework with them every night and I sang them lullabies.