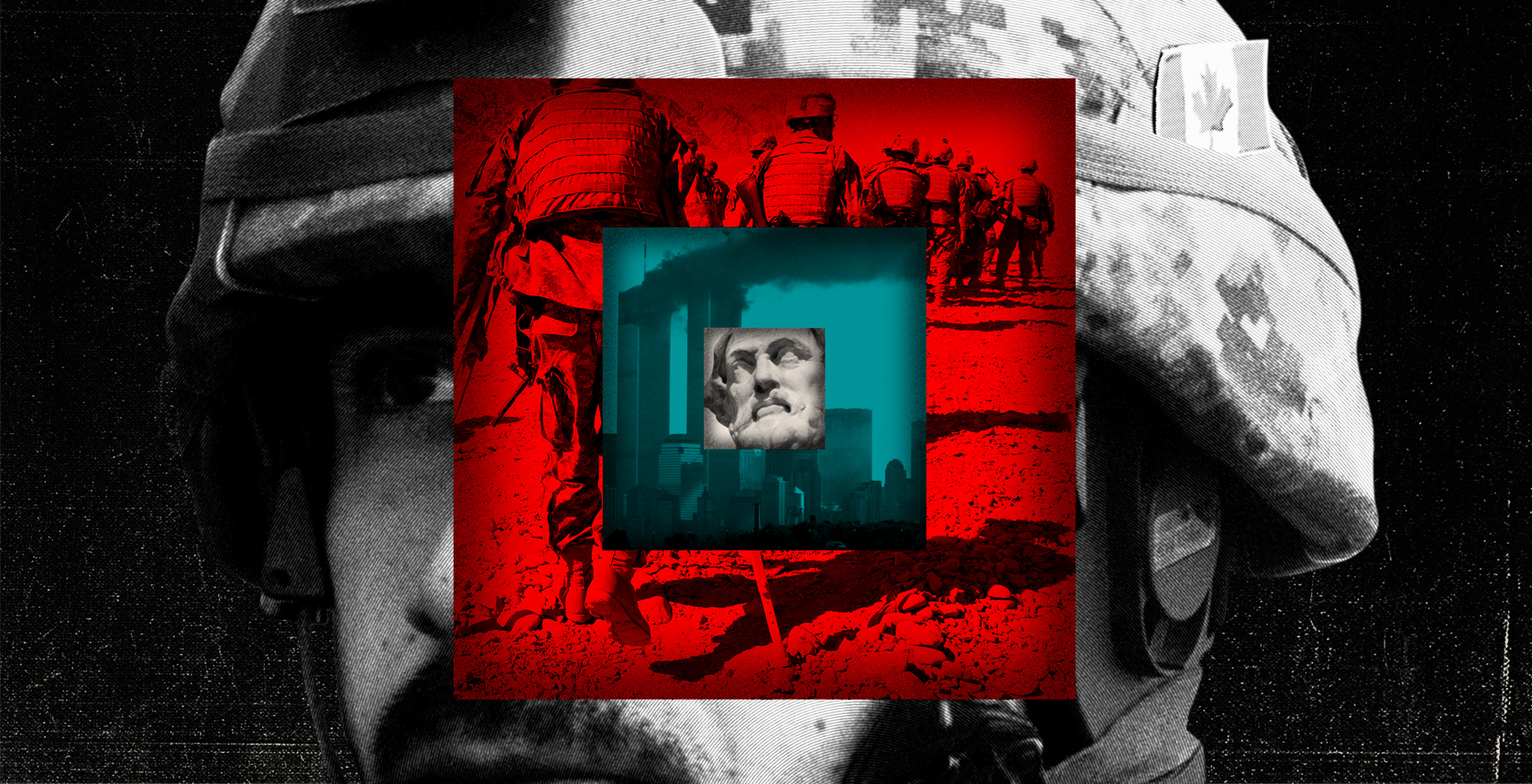

Lost War: What One Canadian Armed Forces Doctor Saw in Afghanistan

A failed war has a shameful melancholy about it that prompts one strongly, and for a long time, to just try not to dwell upon it — the love affair gone ugly, that DUI you got in your twenties. Bad, but nothing to be done about it now. We had thought things would work out. They didn’t.

A lost war is not like other frustrated ambitions, not like a spirited-yet-ill-fated effort on a rugby pitch. Evil was done, to try to achieve the good that was sought. And whether or not it would have been worth it, had the war been won, with nothing to balance out those evils, they only stand there, accusing. By “evil,” what is meant is, among other things, eviscerated children. Hence the thinking about other things. Hence the marital strife.

And then, a few years on, it seems less necessary to avert one’s eyes. The country takes a look and finds that it is worse than it had supposed. The coverage of a lost war is less voluble than it was while that war was still being fought, and for those who supported it, and fought it, the acknowledgement of its failure is usually quiet. For those who opposed it, celebration is impossible — this is not a referendum that has been won, or unjust law that has been repealed. It is thousands of purposeless deaths. Following the silence: a painful glance, more suited to art than to political rhetoric. The Deer Hunter, 1978. All Quiet on the Western Front, 1929. Or the best, and most melancholy, lost-war chronicle, Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, 400 BCE. We are not the first. Everyone comes to their reckoning eventually.

“Where will there be justice in Athens? There will be justice in Athens when those who are not injured are as outraged as those who are.” – Thucydides

Even in retrospect, it seems inevitable that we would have done it, or something like it. The airplanes went into the buildings and it was like taking a short, fast fist to the nose. For a long moment it was hard even to breathe. And then, rage, welling up, like bloody snot streaming from our faces and a wild-eyed scan for who just did that. After so many decades of insulated quiet this side of the ocean, no attacks ever, and now the worst one. If not on us, exactly, on our best friend, and 26 dead Canadians too, buried in the rubble.

Our friend went mad, and we stood with him. Within a few days Al Qaeda was revealed to be the culprit. The 19 Saudis were shown to us, we were told of the way they enrolled in flying school, eschewing any interest in learning how to land. For more than a decade Afghanistan had been the other Somalia, the wild place where monsters thrive. So off our friend, America, went, to the land of monsters. And we after him, to do Al Quaeda harm. And while we were at it, we’d take out all their friends, too.

“Few indeed have been the large armaments, either Hellenic or barbarian, that have gone far from home and been successful. They cannot be more numerous than the people of the country and their neighbours, whom fear unites; and if they fail for want of supplies in a foreign land, to those against whom their plans were laid they nonetheless leave renown, although they may themselves have been the main cause of their own discomfort. Thus these very Athenians rose by the defeat of the Persians, in a great measure due to accidental causes, from the mere fact that Athens had been the object of his attack.” – Thucydides

The thing was, this war felt different. The way the Taliban melted away those first few months, the way the Americans took almost no casualties: this was unprecedented. And surely this, we told ourselves, was because it was an unprecedentedly noble mission. What the Taliban did to school teachers. And girls. The plumes of smoke rising out of the Financial District. We were not there for our own strategic advantage and we were not after treasure. We were there for the sake of justice.

The very first Western combat death was that of the CIA officer, Johnny Spann, killed November 25, 2001 when thousands of surrendered fighters rose up in a prison protest near Mazar-i-Sharif. They got theirs a few days later when 7,000 of them were loaded into shipping containers, to be moved to a prison in the south. Two hundred and twenty to a container, denied water, room to move, or even much air, a substantial fraction of them died, like so many Daschunds with the windows rolled up. Maybe thousands. There was no body count and it generated not much discussion when it was reported. It’s called the Dashti-Leili massacre. It’s the sort of thing that happens in all wars.

“Besides, I know the Athenian character from experience: you like to be told pleasant news, but if things do not turn out in the way you have been led to expect, then you blame your informants afterwards. I therefore thought it safer to let you know the truth.” – Thucydides

Then, in a blur, Bin Laden made his way to the caves of Tora Bora. The Taliban were every bit as much the villains of this story as was Al Qaeda, we decided. They had granted AQ succour after all. They knew what AQ was up to — at least in general terms. Yes, the attacks had been planned in Hamburg. And yes, Pakistan gave AQ as much succour as the Taliban ever did. Maybe more. Maybe the Taliban only tolerated AQ in the first place because the Pakistani Intelligence Service told them to. Still. The Taliban were evil, too, and accountable. And anyway, OBL was unreachable now. Pakistan is a major regional power.

“Right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.” – Thucydides

OBL and his colleagues slipped away and into Waziristan. So the West shifted its aim from its target to that which it could reach. The seeds of the subsequent melancholy were sown.

…

IT WAS ALL so confusing to watch from a distance. I had been in the Arctic, in Rankin Inlet on the West Coast of Hudson Bay the day it all started. I was trying to get patients of mine out on a medivac to Winnipeg when every flight on the continent was grounded. Early September, and winter starting already. The mother of my children called me from Saltspring Island to ask me what was happening. All I knew was that there were holes in the ground in Washington and Pennsylvania and New York. It’s all anyone knew. People thought the world was collapsing. You could see their point. I was as angry as anyone.

I was 36, then. I had been a reserve infantry private, and then a second lieutenant, and then an artillery regiment medical officer, a captain, in the ’80s and early ’90s. For years we had braced for the Red Army, and then the Red Army went away, bled white in the Red Desert, and returning to Americans the Clintonian Peace Dividend. The French chafed at the consequent Hyperpuissance but nevertheless, the End of History was proclaimed.

And then this new puzzlement had unfolded. In the arctic my apartment was small and libraries are hard to carry in suitcases, so the books I picked to take up there were ones of density, which submitted to and rewarded rereading. I had bought my first Thucydides in the Borders book store in Lihue, Kauai before setting out across the North Pacific by myself in a little sailboat. I needed something arresting to distract me from the expanse of the horizon and the silence of such solitude. I am no classical scholar and most of his subtext no doubt escapes me, but he easily is the most readable classical writer I have encountered, and the melancholy of his story haunted me. He refutes neatly so many of the nostrums we support ourselves with. Tyrannies become brittle and inevitably fall, we tell ourselves. We saw it in Eastern Europe, had spent decades telling ourselves that it was bound to happen — but here was the old Greek, warning us that events do not always proceed as they ought. In war, as in anything.

“Think, too, of the great part that is played by the unpredictable in war: think of it now, before you are actually committed to war. The longer a war lasts, the more things tend to depend on accidents. Neither you nor we can see into them: we have to abide their outcome in the dark. And when people are entering upon a war they do things the wrong way round. Action comes first, and it is only when they have already suffered that they begin to think.” – Thucydides

And despite our evident good intentions, things in the desert began to unravel. The Taliban, dispersed, reconstituted itself. It became no longer possible to travel the highways without guards — and then without armour. Our friend threw himself at a — not innocent, but certainly uninvolved — bystander. That was his fight, not ours, not yet, anyway. We let him go at that one alone. But it distracted him, and pulled his attention away. Things got worse quickly, for us and everyone there.

Canadians went from Kabul to Kandahar. The fighting was intense there and the little field hospital that the Canadians ran in Kandahar had a busy ICU. The workload was heavy and the small contingent of Canadian military surgeons, internists, and anesthetists were cycled through quickly. They got tired. A call went out, asking for help. I said I would go.

Thousands of other young men and women said they would go, too — not just soldiers, but diplomats and journalists and aid workers. They went because it was their job, partly, but also because they were excited by the collective undertaking. Millenial ennui was dispelled for a moment and who could resist being stirred by the bagpipes played at the ramp ceremonies? We are wired for tribal battle, deep within our thalami, no matter how well thought out our liberal sensibilities may be. We live lives of peace and ease; we wear our bicycle helmets and seatbelts and show up at work on time and go to the gym afterward to try to lose those ten pounds. All the satisfactions of that life looked limp beside the chance to fight a just war.

“And their judgment was based more upon blind wishing than upon any sound prediction; for it is a habit of mankind to entrust to careless hope what they long for, and to use sovereign reason to thrust aside what they do not desire.” – Thucydides

…

I AM NOT sure just when it was that it became certain that the West would lose in Afghanistan, but it was becoming clear in the spring of 2007. There were worrisome signs already, then. The Iraqization of Afghanistan was already well underway: the Taliban avoided firefights with the West by then, preferring to fill pressure cookers with diesel fuel and fertilizer. Canadian generals had bragged about a one hundred to one kill ratio, but that applied to fire fights of the year before more than it did this sort of war. At night the men dug holes in the road. In the morning the soldiers went out to try to find them. And they did.

The whole time, the West tried to persuade itself that it was welcome. We commissioned polls asking the Pashtun if they supported the presence of the NATO forces in their country. Unsurprisingly, the answers were mostly “yes.” Who else would be asking the question?

We defined success by the number of clinics we had built, the schools that had opened, the children who had been vaccinated. The Taliban defined success by what the farmers did when they said they were spending the night in their compounds. What they did was, say ‘yes.’ To the men speaking their own language, who grew up in the next valley over. And in the morning, when no missiles had struck their houses, and the column of men moved on, the farmers were just relieved. And wished they didn’t have to worry about the missiles part.

He is called the “Father of History.” I read Herodotus in the South Pacific, prompted, like everyone else, by Ondaatje’s The English Patient. But it is Thucydides who values dispassion above all and rejects mythology and the supernatural. There are no gods active in the Peloponnesian War. Only men, so easily stirred by their own vanity and passions. The wine-dark sea swept over the bow of my little boat, and though I had Homer with me too, I revelled in the comforting paternal wisdom of the first documentarian. Be cautious with your own emotions, he told me. You are tired. When you are discouraged, you are too pessimistic. And when you are elated you are too optimistic. Yes, that is a beautiful sunset, and the wind is just right. But there could be trouble with the next wind shift. There probably will be.

We crossed an ocean together, Thucydides and me.

Which is why I returned to him. Packing hurriedly before I left, I piled favourite and unread books into my duffel bag. I thought for a second before tossing him in too. His astringency, it seemed to me, might go down well, while over there. And I loved his writing while at sea — at war, he would be even more powerful. I was not skeptical, then. Even Thucydides allows: if you believe in something, you have to try. Canadians conceived the Responsibility to Protect doctrine, after all.

…

IN KANDAHAR, we took turns giving talks in one of the canvas tents we used as a meeting room. War catalyzes improvements in trauma care like moonshots do electronic miniaturization. We all changed our approaches to resuscitation, to transfusion, to post-operative management. The surgeons started talking about damage control philosophies — trying to do the minimum necessary, that their battle wounded might survive to deal with the deferrable problems. These were ideas that would follow us home, and influence our approaches to trauma patients for the rest of our careers.

I gave a talk about the role infections played in war. In the immediate, post-op wound sense — and in the epidemiologic sense. I talked about the Spanish Flu of 1917 and, inevitably, I talked about the Athenian Plague. About what Thucydides had to say about it. Plagues come to war-battered societies for the same reason infections complicate battle wounds. Death — of tissues, social order, ideals — invites contagion.

As I spoke, one of the surgeons in the tent, a young lieutenant colonel, blond and — though he disguised it — a reader, pricked up his ears. He had been reading Thucydides too, and he was way ahead of me. He knew what was going to happen.