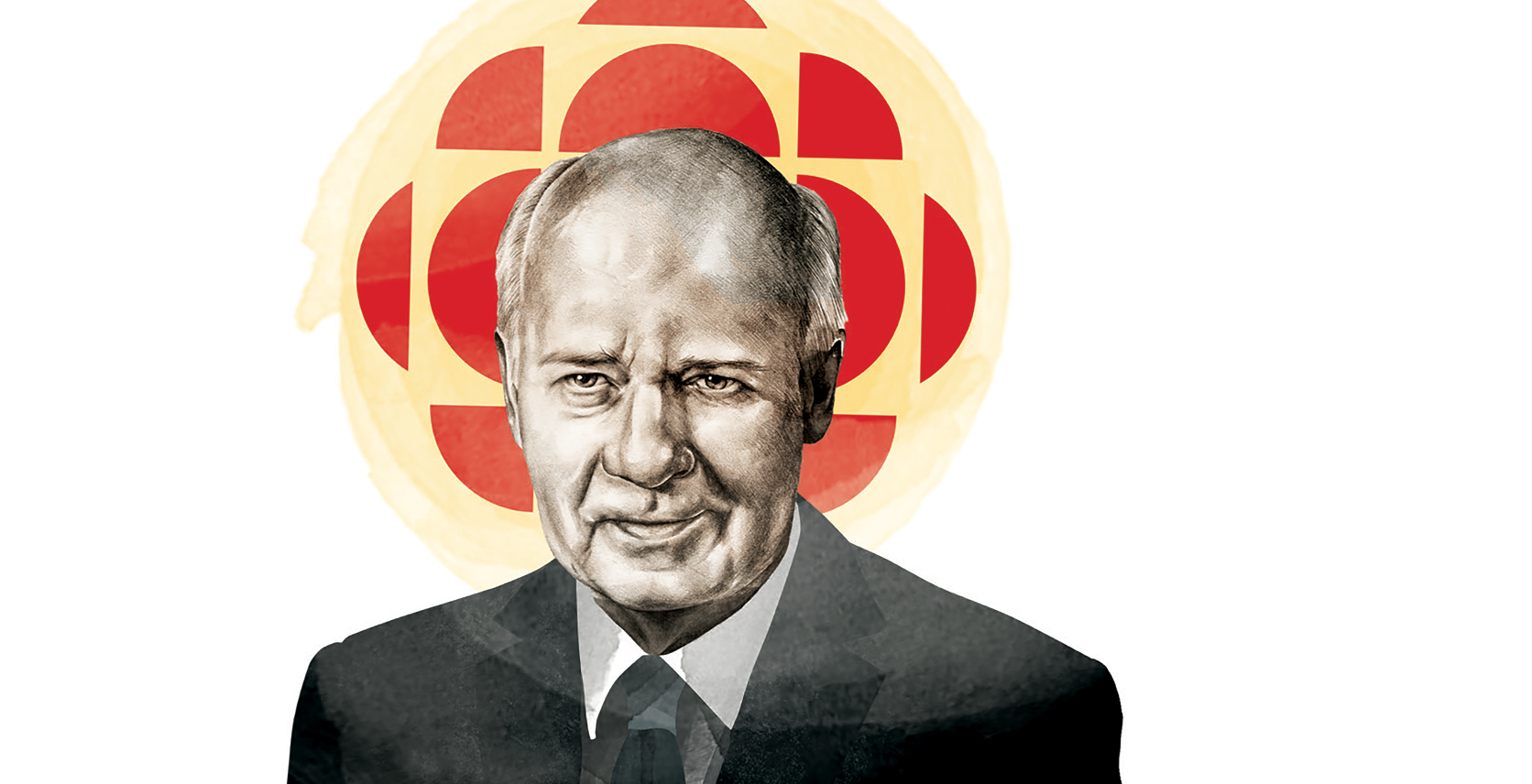

Peter Mansbridge: “News Organizations Have Forgotten the Basics of Good Journalism”

Peter Mansbridge is an institution. He’s been on the radio and television airwaves for nearly 50 years, since he and his signature baritone announcer’s voice were first discovered in an airport in Churchill, Manitoba in 1968. Mansbridge has served as a beat reporter, a national politics correspondent, and, since 1988, as anchor and chief correspondent of The National, CBC’s flagship evening news program.

If you’ve spent any time watching television in this country, no doubt you’re familiar with his work. He has been the familiar face guiding us through tragedy (the death of Princess Diana, the 1995 Quebec referendum, 9/11), celebration (the fall of the Berlin Wall, the inauguration of Barack Obama, countless Olympic Games), and two Prime Ministers Trudeau. Through it all, Mansbridge became known for his unflappability, his good sense, his professionalism — and his constant, unwavering belief in the power of journalism and the importance of telling Canadian stories.

This July 1, Mansbridge will hang up his cue cards and retire from his post on our national airwaves. Before he leaves, he shared a few of the things he’s learned along the way.

Thirty years into this gig, do you just show up at ten minutes to ten, look at your cards and…

[Laughs.] Yeah, that’s what a lot of people must think! But no, I’ve always been a big believer in being involved the whole day. The first meeting I’m involved with is at nine o’clock in the morning, and at night I don’t leave until 11 at the earliest, much later if we have some developing story.

Are you looking forward to retirement?

There’s obviously mixed feelings. I made the decision a few years ago, actually. I’ve been involved with journalism every day for almost 50 years. I’m going to miss certain elements of that, but I’m looking forward to what will be a new phase of my life both personally and professionally. I’ll stay involved with journalism and I’ll stay involved with the CBC, just on a different level.

So why now?

I had always felt that my expiry date would come at the same time as I reached my seventieth year. That happens this summer. There are so many things happening in our business — so much change in the way we can tell stories through technology, that I think it truly is time now for a new generation of thinkers.

Tell me more about that. How have you seen journalism change over the last 30 years?

Well, keep in mind that when I started in the ’60s, it was black-and-white television, right? The first big change I saw was going to colour. We used film, which you had to send to a lab to get processed, and then when it came back an hour-and-a-half late, you’d physically cut it and tape it together — I mean, we’re a long way from that. There have been all kinds of moments of significant change in the 50 years since. The problem is, most of that change happened in the last 10 years. New technologies have allowed us to do things a lot faster. But what hasn’t changed is the power of good storytelling. If you can marry that with the advances in technology, you’ve got a great product. If you let the technology get ahead of journalism — context, accuracy and all that — then you’ve got a problem. And you do see that problem come up at different times for different news organizations, where they’ve either forgotten or are ignoring the basics of good journalism.

So let’s talk more about those basics. I mean, we’re in the era of “fake news.” What does that kind of rhetoric mean for your business?

It means you’ve got to be sure of what you’re doing, and that you can counter that argument. There have always been elements of criticism to what we do, but they’ve never been quite as loud or pronounced. And they’ve never had as their champions people of such significance within society as we see now.

We have to be able to stand tall and proud, and be transparent about what we do. There’s a large responsibility being the public broadcaster. We’re accountable to our shareholders: the public, not the government. There are good, sharp questions about how we make the decisions we make, and we should answer them as directly as we can.

Why is journalism worth fighting for?

Journalism matters because it is a fundamental pillar of any successful democracy. It gives the public information; it allows them to understand the issues of the day in a fair, and accurate, and in-context fashion. If you don’t have that, you live in a world where the information you’re getting is often torqued in favour of those who are giving it to you, whether governments or businesses or whatever. I mean, bad journalism should be attacked — and I have no problem with that — but good, solid, hard-hitting journalism, that’s what we should do.

“New technologies have allowed us to do things a lot faster. But if you let the technology get ahead of journalism — context, accuracy and all that — then you’ve got a problem.”

Let’s go back a bit. You’ve had what some people would call a “dream career” — but was that your dream?

I can honestly tell you I had never thought of journalism or broadcasting at all when I was growing up. When I left high school I went and joined the Navy. I wanted to be a pilot. I wanted to fly off an aircraft carrier. That didn’t work out. I ended up working for a small airline in northern Manitoba, and by a fluke, somebody heard my voice over the PA system. The guy who was running that station couldn’t get anybody to do the late night shift. So he was literally going around listening to voices and offering the job. He heard me in the airport, and he came up to me and said, “You’ve got a good voice. Have you ever thought about radio?” I hadn’t. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life — I was only 19 — and I thought, “Why not?”

I was a DJ at the beginning, which I knew wasn’t going to be my future because I didn’t really know music — but I did love the idea of news, and there was no newscast there. I suggested that we start one. And with no training, no understanding of how to do that, I started a newscast: two or three minutes of talking with the RCMP and what they’d done in the last 24 hours and talking to people at the equivalent of city hall and the school board, then it just expanded over time. I made a name for myself. They heard about me in Winnipeg and in Toronto and I moved along.

You’ve been on TV a long time, playing a TV version of yourself — that’s the person everyone knows. So, who is Peter Mansbridge really?

I always tried to be myself, but because the demand is one of being that kind of neutral-voiced, calm, reasonable person that’s telling you what happened in a day, it comes off in a certain way. It took a while to feel comfortable in that role. First there was the nervousness of doing it, because, “Oh my God, I’m doing The National.” Then there was trying to find that spot, your own persona. In my case, it took a couple of years at least before I was very comfortable in doing it.

You’ve made a career of interviewing people. What’s the one question you always hoped someone would ask you?

[Laughs.] I suppose it’s somewhere around, “Why have you stayed in this business of journalism?” Because, like a lot of people, there are other things that I could have gone into. But I love the job because it is… fun is probably the wrong word, but it can be so much fun to have that opportunity to work with other good people who are trying to tell the details of an important story. And almost every day there’s something new; you’re dealing with new issues, you’re learning new things, you’re interviewing new people. It’s an exciting job. I do get uncomfortable with some of the attention I get. I’m just a journalist, right? I’m a storyteller.

And there are lots of people like me in this business that don’t get the same kind of attention that a television news anchor gets. I’ve always found that somewhat unfair. Lots of people come up to me on the street, in airports, people shout at me from cars, in the shopping mall, in the grocery store, people I don’t know who come up and say some version of, “Have a great retirement. I don’t know what it’s going to be like without you. I’ve watched you all my life.”

And that’s flattering and it’s humbling, but the more I think of it, rather, the more I realize that what they’re saying isn’t really about me, it’s about them. And what they’re saying is that there’s been a certain touchstone within their life, whether they even watch the news or not — maybe they simply saw me when flipping through the dial — it was a part of their life that was a constant. When you take that away from them it’s disrupting for a moment while they get over it. Something that’s always been a part of their life is suddenly gone, so they’re feeling the difference. They realize they’re older. You know, if that person who’s always been a constant is suddenly so old that they can’t do it anymore, then it must mean that they’ve gotten older as well.

I’m sure you’ve been thinking a lot about your final sendoff on your last National, but if you had to leave us with some final words right now, a piece of advice or some wisdom, what would that be?

My advice to them would be to always demand more from your journalists, and the journalistic organizations that you believe in. You want the truth. You want the facts as best as they can find them. You don’t want those facts torqued in any particular way. You want to be able to make the decisions yourselves for what’s ahead. You should demand accountability from the public broadcaster on the way they do their work.