Can We Fix the NFL?

A little while ago, on a Sunday mid-way through the NFL season, I went to a bar with a couple friends to catch the late-afternoon games.

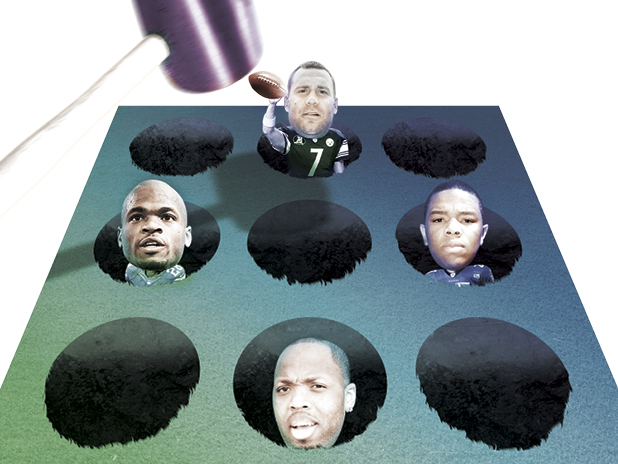

Like so many pleasures in 21st century life, football fandom requires a certain amount of moral equivocation. I eat meat, sure, but I often spend a couple extra bucks to get the “free run” chicken. This, I like to tell myself, is compromise enough. I consume football the same way—guiltily, hungrily, trying my best to avoid the most obviously immoral products. And so, I don’t cheer for the Washington Racial slurs. I refuse to put accused rapist and convicted asshole Ben Roethlisberger on my fantasy roster. I’ve learned not to applaud when I see the kind of bone-crunching hit that, we now know, leads to brain-trauma and early-onset dementia.

In the past, these tiny compromises have been just enough to help me not feel like a total monster for enjoying a Sunday of football. But as the ESPN homepage begins to look more and more like the crime section of a newspaper in a particularly unpleasant city, the moral gymnastics necessary to watch a game feels more like outright hypocrisy. That afternoon, looking through the various games playing on the bar’s televisions, the cheering options were slim. The Cardinals? The team that continued playing running back Jonathan Dwyer after an investigation into a night in July when he allegedly head-butted his wife in the face, breaking her nose? The Panthers, who kept star defensive end Greg Hardy on the roster after he’d been convicted of two counts of domestic violence?

And then there were the Ravens. All season, the story of running back Ray Rice’s vicious attack had hung over the game. The video was inescapable. The image of a 212-pound man striking his girlfriend and then dragging her unconscious body from an elevator with the same care you’d treat a cumbersome piece of luggage was impossible to forget.

The images were arresting, but what made them particularly affecting was the queasy sense that the violence they depicted wasn’t something incidental to football. If you’re a football fan, the worry is that the toxic masculinity on display in the Rice video isn’t something that can be neatly excised from the game—a tumour that can be removed without harm to the rest of the body. The fear is that it might be something more essential to the sport’s appeal, something closer to its heart.

Professional football doesn’t have a monopoly on shitty behaviour and the NFL isn’t the only league whose players get into trouble (or don’t) for it. Bobby Hull, a hockey great whose formers wives have reported serious domestic abuse, remains an official ambassador of the Chicago Blackhawks. A story by former MLB pitcher Dirk Hayhurst last summer detailed the poisonous misogyny of baseball minor leaguers who view women as “points” and do whatever they can to score, including acts that can only be called sexual assault.

What sets football apart—beyond the sheer number of incidents and the way the league has seemed content to brush them under the rug—is the way that violence and poisonous masculinity seem so entrenched in our experience of the game.

The league has grown into a $45-billion business by mass-marketing its particular vision of masculinity, selling it to wimpy, writerly fans like myself and my friends. It’s a strangely appealing vision. In a world where ideas of “manliness” are quickly changing (see: this magazine), the NFL sells a glamourized, anachronistic vision of masculinity that is totally unrelated to the day-to-day lives of the accountants, bartenders, executives and magazine writers watching at home.

Football players leave it all on the field. They’re courageous, physically gifted, and violent. They love one another like brothers, battle like warriors, sacrifice for their teammates, fight through pain and adversity—all admirable, traditionally masculine virtues. This vision of manliness isn’t some small part of the NFL, but the core of its popularity, and the league knows it. It’s evident in the entire package that surrounds the broadcasts: the clubby pregame show in which thick-necked guys called Boomer and Tony and Bill perform an elaborate pantomime of barroom bonding, the jokily misogynistic commercials for light beer that fill every break in the action, the insistent presence of the military, with the fighter jet flyovers and constant martial metaphors.

Perhaps it’s most evident in the way it treats women. Despite making up 45 percent of the league’s fans, women have a very particular role in the NFL. They are opinion-less sideline reporters or midriff-baring cheerleaders. We see glimpses of beautiful girlfriends in the press box or “honey shots” of hot fans in the bleachers. When Michelle Beadle, a rare high-profile female pundit on ESPN, dared question a colleague’s insinuation that Ray Rice’s wife might have “provoked” her attack, Beadle was inundated with vile abuse from football fans. The message was clear: know your place. The other side of the NFL’s pageant of manliness, then, is the simple fact that the league doesn’t seem to value women. The masculinity it celebrates too often curdles into something rotten.

As fans, we’re reluctant to acknowledge this. A fundamental reckoning with the toxicity in the sport threatens to ruin the fun. Football, after all, is supposed to be the last vestige of all those enjoyable manly things that politically correct scolds and meddling women have eradicated from the rest of society. And so most fans are content to ignore it until, with moments like the Rice video, we’re compelled to pay attention. The NFL is the way it is because fans don’t force it to become better.

Perhaps the most telling moment in this season of football violence came in the days just after the Ray Rice video came to light. On a Thursday night in September, the Baltimore Ravens played in front of a sold-out crowd and massive television audience, all eager to see how the team would respond to days of chaos and criticism.

During the pregame introductions, Ravens linebacker Terrell Suggs decided to run onto the field in a silver gladiator helmet. It was an inspired stunt. There he was, the embodiment of the athlete-as-warrior, a 260-pound bruiser promising that, like Russell Crowe’s Maximus, he was prepared to battle for your entertainment.

Suggs is a star. He’s the former defensive player of the year and a six-time pro-bowler who signed a four-year, $16-million contract extension with the Ravens last winter. He is also a man who has been accused of multiple cases of domestic abuse that make Rice’s attack look tame. In 2009, Candace Williams requested a protective order against him after she says he knocked her to the ground, grabbed her neck, and held an open bottle of bleach over her. Three years later, Williams asked for another protective order after Suggs allegedly punched her in the neck and dragged her alongside their car as he drove away with their two children inside.

Suggs was never suspended by the NFL. There was, after all, no video. That Thursday, he danced onto the field a beloved star in a league that seems content to embrace violence on the field and ignore it everywhere else. Suggs ran through the tunnel and onto the gridiron, helmet gleaming. He pumped his fists and flexed. The crowd went wild. It was the essence of football. Are you not entertained?

Illustration by Dan Raftis