Hugh Laurie on ‘The Night Manager,’ Outrage Culture and Playing the Blues

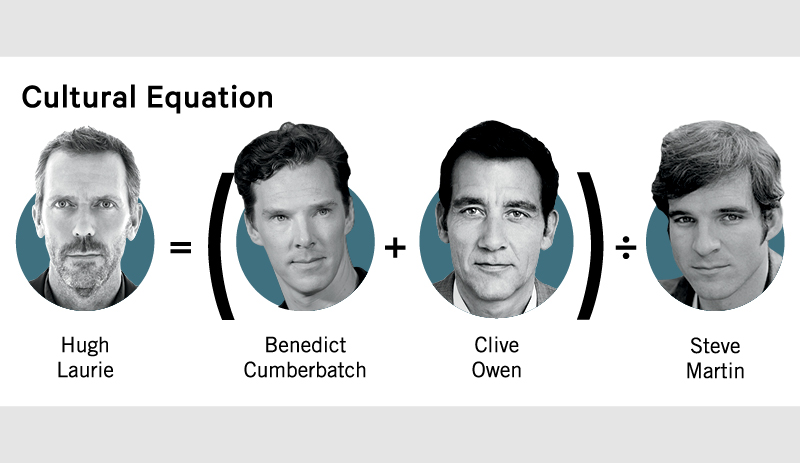

You probably know one of two Hugh Lauries. For those who still remember the ’80s and ’90s, or who inexplicably keep PBS on at all times, he was the gangly straight man to Stephen Fry’s bumbling goofball in shows like A Bit of Fry & Laurie, Jeeves & Wooster, and Blackadder. For those whose cultural diet consists mainly of US cable TV, you’ll know him as Dr. Gregory House, the curmudgeonly diagnostician with a limp and a flawless American accent.

But the truth is, there are many more Hugh Lauries than that. He’s the author of a comic spy novel, The Gun Seller. And he’s recorded and toured two albums of New Orleans blues, on which he sings and plays the piano. These days he’s back and forth between England and LA, moving between comedy (he’s a regular on Veep) and drama — his latest project is an adaptation of the John le Carré novel The Night Manager, wherein he plays Richard Roper, an arms dealer often referred to as “the worst man in the world.”

As for the Laurie you’d know if you really got to know him? He’s a reader, an art lover, a big thinker. He’s someone who sees the light in the dark — and, just as important, the other way around.

What compelled you to do The Night Manager? Are you a big Le Carré fan?

Always have been. Le Carré was a sacred text growing up. When the Cold War was officially pronounced over, I feared that Le Carré would be out in the cold, to use his own phrase — that spies would be out of a job, and so would spy writers. The Night Manager was the first novel he did that was not set within the confines of the Cold War. I was nervous about it. I remember, I sat down to revisit it — it had been about 25 years — and I got three chapters in and I actually stopped and got on the phone to try to option the rights to turn it into a movie. It was the only time I’ve ever done that — I’m not a producer. But this was a story that had to be told.

The novel is actually rather different, in that the world into which Richard Roper is trying to sell these deadly weapons is the world of the Colombian drug cartels. That has been transplanted into the modern age, where it’s set in Egypt and Syria and all those countries that dominate the headlines. Even though, I suspect, the Colombian cartels are no less deadly than they were 25 years ago.

Why do an update now? What do you hope it says about our modern world?

Well, the spy genre is sort of eternal. It’s like our [British] version of the Western. I mean, Tarantino has a Western in a cinema near you right now. They’ve never gone away. (The only problem with Westerns is that you cannot find actors who can ride horses anymore. Although the same can probably be said of actors who can drive cars in a Cold War spy movie.) I think that, rather like Westerns, there are certain rules that serve both the storyteller and the audience. There are a number of givens about the world that you’re watching: what’s at stake, what we believe to be good and evil, what betrayal means, what honour means, what sacrifice means. And that allows storytellers to go further in a short amount of time, because there’s a familiar vocabulary.

That allows someone like Le Carré to get into a certain amount of depth. The Spy Who Came In From The Cold was a defining novel — without it, perhaps there wouldn’t have been 10,000 novels since about a spy trying to find honour in a shabby world. More than perhaps any modern writer, he can claim ownership over this particular dramatic world. And more than all that, I just think he’s a terrific writer. He’s funny. He’s righteous. That’s an uncommon thing in writers these days, for him to have maintained his anger and sense of outrage. I mean outrage not as a petulant, complaining thing, but as a sense of life and justice and fairness. I think it’s a really wonderful thing. And I don’t see that diminishing in him at all.

Some people might argue we’re in an age of rampant outrage — where everyone is outraged all the time…

Yes, they are. But they’re outraged in a sort of self-serving way. They’re outraged to show that they’re good people. It’s a way of declaring to the world what high moral standards you have if you can show to be indignant or hurt or agitated by some high moral injustice. But that, I think, is a sort of fake version of what Le Carré has always felt very deeply. I don’t think he cares what people think of him. I think he’s very much offended by injustice and betrayal and all those big things that we ought to be offended by. But he’s not doing it to gain favour, which I think is what so many people do nowadays. They try to gain credibility by showing how shocked and affronted they are by everything. It’s very tedious. I just don’t find it tiresome coming from him, because I think it’s the real thing.

The other great thing about The Night Manager is that it proves just how great British villains are.

Someone — who was it? — first remarked that British actors get hired to play either God or the devil but not much in between. Ralph Richardson was a really wonderful God, but also could be a fantastic devil. I wonder why that is? It’s an interesting perspective. We in this country — in England — we would think — you’re Canadian right?

Yes.

Over here, we regard Americans as… the fringes of their bell curve always extend farther than anybody else’s. They’re both smarter and dumber. They go in both directions. Their craziness is crazier than anybody’s, their sanity is saner than anybody’s. They have a very large footprint. Is that how Canadians see them?

I think so. We have the same critical distance as you, only we sound like them, which is confusing for us.

Only a tiny bit, but I’ve got the measure of you now. I’ve worked with Canadians for years doing House. David Shore, the creator, is Canadian. He had a kind of sardonic distance from the normal American dramatic landscape. He could look at the idea of the conventional hero in a slightly more ironic way because he was not from there. I think it was maybe to his advantage, and maybe to mine.

Speaking of House, has it been difficult to make career choices in the wake of such a profoundly successful show?

Maybe it’s a failing of mine. Maybe I should be fretting about that more than I am. But I’m so proud of House and what that character stood for and what the show stood for and the things that they did, that I can’t see it as any kind of confinement. I think there are actors who become known for that laxative commercial and never shake it off, or some role that they hate or didn’t feel was worthwhile. I’m not that person. I’m immensely proud of House. If anything it’s the reverse. I think it’s given me opportunities that I otherwise wouldn’t have had.

And you’ve had lots of opportunities. You’re a bit of a polymath: you act, you’ve written a novel, you have a couple of blues CDs. So what did you really want to be when you were a kid?

Well, who didn’t dream of being a musician? As teenagers we all go through a phase of wanting to be Jimi Hendrix. And then we realize that’s not going to happen. I always thrilled to jazz and blues. It was something I wanted to play. I suppose, if I could go back and make a choice, that would be the one. I’d have worked harder on my scales, certainly. I don’t think there’s a human alive who’s glad they gave up the piano. Everyone wishes they’d done more of something, and that happens to be mine. I wish I’d started earlier.

What is it about the blues that speaks to you?

I honestly don’t know the answer to that. I do know that I’m definitely not the first Englishman to have responded to this music from thousands of miles away and about a hundred years. Why did it speak so deeply to me? I just know that the first time I heard it, it was like an electric shock. And I’m still reverberating from that shock. I suppose a musicologist would say there’s an English resonance — that it’s folk music, Celtic music, church music that have bounced back and forth across the ocean, and when the dice finally stopped rolling, it came up with blues music written on the top. I really don’t know. But I do know that from the first moment I heard it, it was what I wanted to hear, what I wanted to play, what I wanted to know more about, to be a part of. I listen to it every day. I try to play it every day.

Do you think you’ll go back to comedy?

I hope so. I mean, I think I had the best of all possible worlds with House. I found House a very funny character on a very funny show. I thought his wit and his sense of place and his comedy were a very big part of who he was. And honestly, I think it’s a very big part of who people are. No drama can be good drama — truthful drama — if it isn’t on some level funny. Because life is comic. It’s the way people deal with all kinds of things. I’m always looking for it and always hoping that it’ll be present in what I do. And actually, I think it’s in music too, as in all good drama. In a way, I don’t separate them. I don’t think of comedy as a genre, I think of it as being an element of life — and one of the greatest elements of life: that we find humour in existence. It’s of the essence. It’s what it means to be human. Boy that was a resonant last phrase, wasn’t it?