Clash of Kings: Inside the Sexy World of Championship Chess

For 19 days in November, 10,000 spectators gathered in New York City to watch two men fight in a soundproof room. They were brilliant men, with unusually powerful minds. They were silently torturing each other, both coming dangerously close to mental collapse. The reward was world supremacy, as well as the lion’s share of 1.1 million Euros. Welcome to the World Championship of Chess.

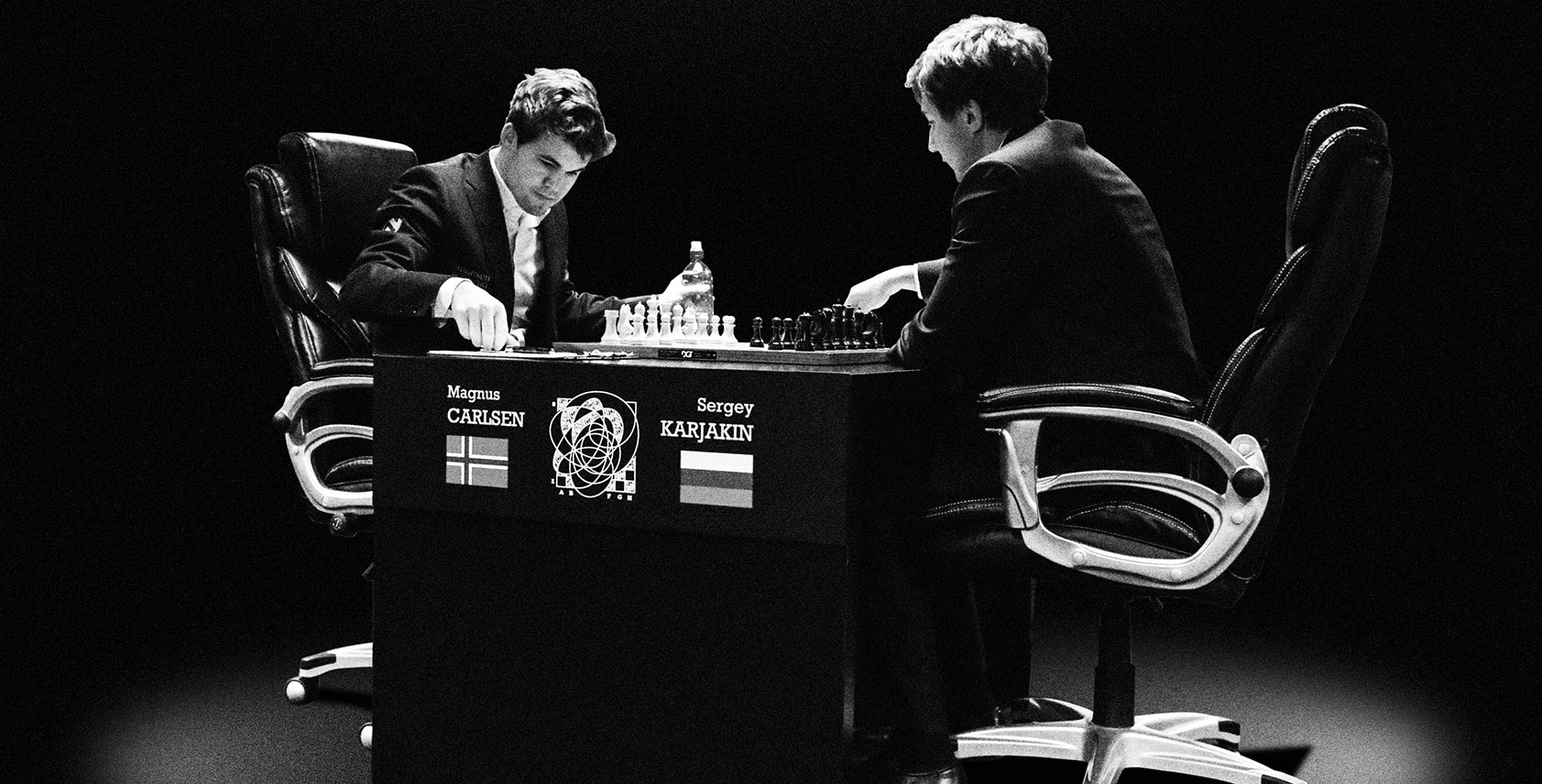

The contestants were Magnus Carlsen, the champion, and Sergey Karjakin, the challenger. One of the room’s walls was glass, and, on the other side, in a dark corridor, stood a crowd that skewed white, male, paunchy, and bespectacled. If there were blazers, they were ill-fitting. They were possessed of the stiff posture you might expect from witnesses at an execution. But the staid silence was pregnant with a potent mix of two emotions. The first was awe at merely being in the presence of such luminous minds. The second was jealousy — knowing that you couldn’t do what they were doing.

Unlike, say, mixed martial arts or NASCAR, every chess fan is a chess player. And chess is a brutal sport. Being a serious player requires hundreds of hours of seclusion — while other people are dating, you’re unlocking the meaning of phrases like “the Nimzo-Indian Defence” or “the Philidor position.” While other people are drinking and dancing, you’re playing in small weekend tournaments in church basements.

The learning curve is much steeper than with other sports. Achieving very basic competence is hard. Becoming a middling player takes at least five years of constant training. If you get all the way up there, life is good — year-round, you fly to tournaments in Bilbao or Azerbaijan, staying in luxury hotel rooms while competing for prizes in the low six figures. But there are few rewards for the vast majority of the more than 65,000 tournament players registered with FIDE, the World Chess Federation. Most of the spectators present at the Championship spent solitary years chasing unattainable dreams, and outside of the top 10 players in the world the money is scant or nonexistent. Aside from the satisfaction of occasionally making a brilliant move, they get nothing.

By “they,” I also mean me. I suppose I was first drawn to chess because it gave me a chance to, finally, be the bully. After being bludgeoned by my physical betters in high school, I could sit down at a board and make another smart kid feel stupid. All of the unpleasantness of my awkward adolescence — the jeers, the mismatched socks, the brown-bagged bologna sandwiches — disappeared as I traveled to a dimension of pure thought where I could kick your ass.

And I did, in fact, kick a small amount of ass. For example, I could probably make mincemeat of the chess hustlers that hang around in sketchy parks. I could definitely, easily beat you. On my high school chess team, the Pawnishers, I was a secret weapon — inconsistent, but occasionally capable of upsetting much stronger players. I became just good enough to realize I was never going to be great. My style was playing very boring, safe maneuvers until my opponent got tired and made a mistake. When I played against people who didn’t make terrible mistakes, I was out of luck.

Eventually, I couldn’t stomach my mediocrity. Also, my pain-in-the-ass genius brother was better than me, which was humiliating. So I went and pursued other things that teenagers do, like sex and drugs. But I always liked chess better. It had a purity, an exactitude. Unlike most human affairs, chess doesn’t rely on chance, or charm, or the right set of social connections. You make a good move or you don’t.

That’s a beautiful clarity. Although I make my living as a writer, I’d trade any writing abilities I have for first-class chess genius without a second thought. Chasing the exactitude of chess seems more satisfying than playing among the vagaries of language. So I came to the Championship to experience, first-hand, the intelligence I couldn’t attain. And although the biographical details would vary, I think everyone else was there for the same reason.

Beyond the dark corridor, we collected in a larger viewing gallery, consisting of a large cluster of tables, each equipped with a chess set. You need a board when you watch chess because people observe the game the way children watch Spider-Man cartoons, leaping off couches and kicking imaginary foes, taking in the action on the screen by mimicking it. Unlike in real-time rock ‘em sock ‘em sports like hockey, chess allows you to play the very same game you’re watching at the same pace it’s being played — you can reconstruct the position the players are dealing with, and attempt to think the thoughts they might be thinking. Four or five people sat around each board, debating about which move the potential champions should make.

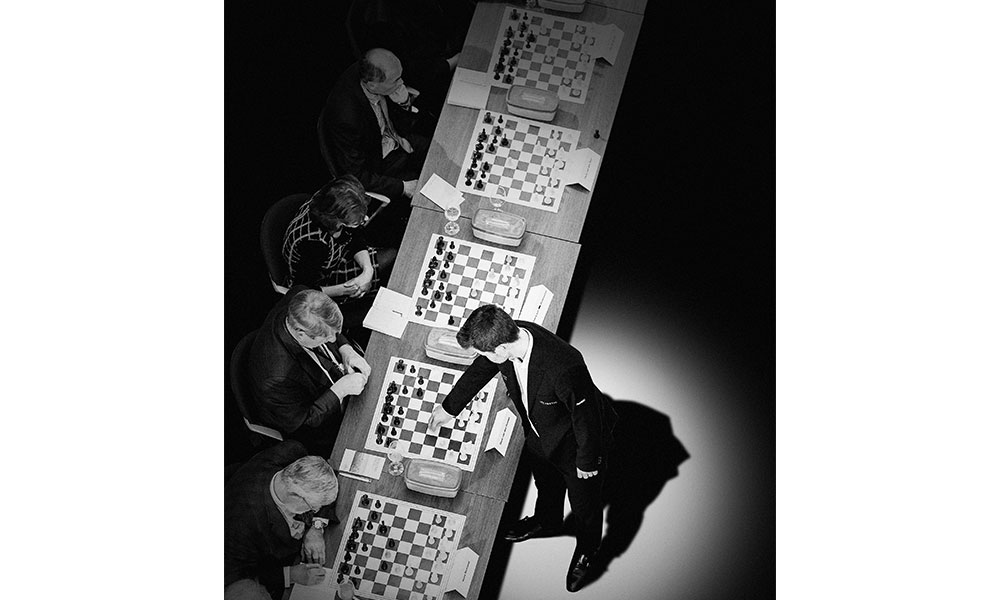

We were usually wrong. After all, they were about 70 times better than we were. That figure may sound like a cartoonish, hyperbolic number picked out of the air to prove a point, but it isn’t. In February, in Hamburg, Magnus Carlsen played a match with 70 other players at once. For six hours, in a sprawling playing hall, he strolled from board to board, delivering killing blows at each one after considering the position for mere seconds. His competitors were all about as good as I am, or better, and they all had hours in which to contemplate their moves. Magnus won 68 games. One was a draw, and one was a loss — there are two amateur players out there who can say they held off one seventieth of Magnus’s mind.

***

When I arrived, halfway through the best-of-12 tournament, things were going strangely. Everyone had been expecting a walkover, a long, savage beatdown by Magnus, widely considered the greatest of all time. The sports betting website Pinnacle gave Magnus a 78 per cent chance of victory.

Partly, Magnus’s dominance stems from simple mental firepower. Magnus has one of those brains that came from a different factory than ours did. When he was five years old, just for fun, he memorized the vital statistics of every country in the world — population, area, flag, capital city. At around that time, his father taught him the rules of chess, and, though disinterested at first, he started studying the game so he could beat his sisters. Nine years later, he mystified the chess world when he drew a game against Garry Kasparov, the highest-rated player in the world at that point. Chess, like math, or dance, is a mode that some minds fuse with effortlessly. Magnus has whatever that is. He first became World Champion at 22 — the youngest in history.

And, like many geniuses, he gets away with being lazy. When he’s not playing in a tournament, he generally reads comic books, plays soccer, and hangs out with his friends. This is absolutely infuriating to people like me, who have to digest mountains of chess books to be even a little good. “When I am feeling good, I train a lot,” he says. “When I feel bad, I don’t bother.”

His style is cold, clean, and unyielding. While some players are swashbucklers, engaging in wild attacks that might end with spectacular victory or defeat, Magnus slowly advances down the board, placing his pieces perfectly, controlling more and more squares, until you can’t move your pieces anywhere. He displays little weakness while exploiting your every tiny mistake. He’s in no hurry. He’s the chess equivalent to a Terminator. Also, he’s, well, sexy. He looks like Matt Damon, or at least like Matt Damon’s more thuggish half-brother. He’s modelled with Liv Tyler for G-Star Raw. He dresses with the subtle taste we’d expect from any accomplished Scandinavian. Like Muhammad Ali, his arrogance is infectious. As you’d imagine, many young players have Magnus fever. As teacher and grandmaster Alejandro Ramirez told me, “He’s really bringing back cool to the game of chess.”

“I suppose I was first drawn to chess because it gave me a chance to, finally, be the bully. After being bludgeoned by my physical betters in high school, I could sit down at a board and make another smart kid feel stupid.”

This is notable, because, while chess is bigger than it’s ever been — there are 600 million chess players, from six-year-olds to aging masters, according to FIDE — it’s still not exactly mainstream. It’s sort of a parallel world. FIDE has made meek steps to change this, like holding the Championship in NYC, bestowing it with a VIP cocktail lounge, and bringing in nerd celebrity Neil deGrasse Tyson to commentate. But there’s no getting around the central problem, which is that other sports are much more impressive. Think of a perfect parabola traced by the legs of a gymnast, or the crack of a baseball bat sending a ball on a tour of the upper atmosphere. Even novice viewers can appreciate the spectacle, the physicality. There’s no physicality in chess, no obvious sexuality. The players just sit there.

But Magnus’s good looks and bizarre level of talent make him a star — he’s the jock hero of the losers, the cerebral introvert whose dreamy face made it into the New Yorker. He’s the kind of person I dreamt of being when I first learned the word checkmate. He won’t just beat you beautifully; he’ll look beautiful while doing it.

But, seven games in, Magnus didn’t look beautiful. Every game had been a draw. He seemed like a cat wondering whether he felt like a meal of mouse meat — he wasn’t seizing on the small opportunities he usually used so well. At the press conferences that followed each game, he answered questions with nervy monosyllables. His lack of success was puzzling to the world chess elite. His opponent, Sergey Karjakin, had been underestimated.

***

Unlike Magnus, Sergey isn’t superficially impressive. He doesn’t have the top-shelf looks or the athletic swagger. He’s one of those little men with gentle features who will forever look a bit like a nine-year-old. He has a stutter that he conceals effectively, but never quite completely. Rather than an intellectual fratboy, he seems like a sweet mama’s boy, albeit one that happens to be a genius.

Like Magnus, Sergey was scary good at a very young age. As a kid, he quickly became one of the finest players in the Ukraine. But unlike Magnus, Sergey was a dedicated, by-the-books scholar. He astounded his chess teachers with the speed of his learning: “It’s like a dragon that eats everything it comes over,” said his first coach, Alexander Alexikov, “and you have to keep feeding it.” He worked for nine hours a day.

Sergey shot up through the ranks. He achieved the title of grandmaster — the highest office available in chess — at the youngest age ever: 12 years and seven months. When he was 19, he won the Tata Steel Masters, perhaps the most prestigious tournament in chess.

He had seemingly infinite potential. But in the Ukraine, he had limited resources — soon the country’s coaches couldn’t tell him anything that he didn’t already know. Luckily, shortly before he turned 20, the Russian government adopted him, grafting him onto their giant chess machine. Russia still has a huge state-sponsored chess program, which is why for much of the 20th century chess and the USSR were nearly synonymous. Legendary Russian players like Mikhail Botvinnik and Garry Kasparov sat on the throne for decades. Chess, like Sputnik, was a symbol of Soviet supremacy. Sergey received a government salary and intensive coaching.

He also became a stolid patriot of his new country. Take this Tweet from March 2016, where Sergey responds to Russia’s annexation of his homeland: “Crimeans, I heartily congratulate your return to the native harbour.” On Instagram, you’ll find him wearing a Putin t-shirt, giving a pretty convincing thumbs-up.

But it’s clear that Sergey’s only final allegiance is to the game, and his real home is in the upper echelons of chess. Unlike Magnus, he couldn’t get there without truly intensive study. Pursuing that scholarship meant leaving his home and alienating his old Ukrainian friends, but he did it anyway for a shot at the World Championship. Sergey’s play is accurate and assured, almost scientific. What makes him special as a player is that the bastard just never gives up. While that sounds like an attribute any chess player should possess, being on the losing end of a tournament game is a dreadful matter, because classical tournament games last as long as six hours. The idea is that you’re given enough time so that you can play almost perfectly, but not enough time that you don’t feel intense pressure. Unless you lose quickly, losing in chess is a slow crush of the ego. It’s hard to hang on.

Sergey’s ego is steel-plated. No matter how comfortably you’re winning, Sergey will make it uncomfortable. This made him a perfect foil for Magnus. The Norwegian cages his opponent, but the Russian is an escapist. This seemingly made Magnus angry — an anger that lead to his abrupt, unexpected downfall in the eighth game.

***

The disaster started after a few hours of play, when Magnus and Sergey had reached what chess fans call a “drawish” position — the cerebral equivalent to a boxing match between exhausted heavyweights, all clutches and barely visible jabs. In such positions, the normal strategy is a war of attrition (you take their knight, they take your bishop, et cetera). Then, when there’s nothing left on the board, you go back to your hotel room, stare out the window, and try to somehow slow the neurochemicals that fly through your brain when you think of the next game.

However, Magnus wasn’t satisfied with that. He decided it was time to strike. In chess, again as in boxing, you can’t land punches without exposing yourself to some counters. Magnus advanced the pawns in front of his king — which served as the shield preventing his king from being attacked — to stab at Sergey’s position. When that came to nothing, he rushed his pieces down the centre of the board. His play became, in chess lingo, “sacrificial” — he allowed Sergey to take some of his

He had to decapitate Sergey quickly. In chess, you can either beat your opponent in the near-term, by assassinating their king, or you can win in the long-term, by turning one of your pawns into a queen. If your opponent has pawns at the end of the game, you quite simply lose.

Magnus quite simply lost. His king was running scared, and, on the other end of the board, Sergey had a runaway pawn, about to turn into a queen. Unable to defend against both threats, Magnus resigned. After shaking Sergey’s hand, he skipped the post-game interviews, then stormed out of the press conference.

This is unusual. A big part of chess etiquette is the post-game wrap-up, where the players discuss key moments in the game, often pointing out winning moves their opponents didn’t see. It’s all very friendly — there’s this in-it-together feeling, like, after the heat of the moment, we’re just a bunch of geeks again, enjoying the intricacies of the game itself. By storming out, Magnus violated basic social norms. He also, according to chess federation rules, was fined 10 per cent of the prize money — no small price for a temper tantrum.

This had never happened before. Magnus had never been behind in a world championship match. Chess fans, generally a sedate bunch, don’t usually freak out. People were freaking out. Magnus was supposedly untouchable, but he suddenly looked very touchable. Although the match was only halfway over, a myth was in the making: a champion, lulled into complacency by his dominance, taken out by an unassuming Russian.

Like every non-Russian chess fan, I was a Magnus supporter going into the match. But, after Sergey’s unexpected win, my allegiance shifted. Not just because he was the underdog in the match, but because he seemed like the embodiment of the underdog itself. Simply put, Magnus’s very existence is unfair. Every player in the top 10 — hell, the top 50 — is a person of unusual intelligence and unswerving devotion to the game. But no amount of devotion could win you Magnus’s supercomputer brain. As a result, the general feeling in the chess world was that Magnus would enjoy a comfortable, uninterrupted era on the throne until middle age slowed his impossibly quick calculations.

But if Sergey won, that narrative would go straight in the garbage. A Sergey victory would mean that nobody was invulnerable — nobody’s place in the world was permanently decided by their genomic strengths. Any elite player, if they put in a singular effort, could fight their way to the very top. If Sergey could beat Magnus, I could beat much superior players, or at least my genius brother, if I only put in the hours. This was compelling.

***

Like the best at anything, the World Champion of chess is motivated by failure. He tends to strike back. On the day after his defeat, he arrived at the board with an expression both tranquil and furious. And that’s how he played.

The game initially seemed boring. But Magnus wasn’t content with that. He launched an unusual attack that transformed the game from a tentative skirmish into an all-out war. Although Sergey defended perfectly, and it ended in a draw, Magnus was calling the shots.

Game 10 was pure pain. Magnus got the kind of position he likes — a state of play where Sergey’s pieces were tied down defensively. Compare it to being an MMA fighter pinned to the mat by an expert grappler. It’s possible to escape, but a small miscalculation and you’re choked out. The Russian cracked, making a tiny mistake that didn’t even look like a mistake, and his defences crumbled immediately.

Point to the Norwegian. That made the score one-one going into the last two games. An even score had interesting consequences. Given that draws happen with perfect play, you rule out draws by reducing the potential for perfection: you dramatically accelerate play. So, if drawn, the match — and therefore the championship — would be decided by a best- of-four speed round: four games where the players had half an hour’s time each, rather than over two.

And that’s what happened. Magnus drew the last two games in a clinical fashion, aiming squarely for the chaos of the tiebreak. Fast chess is a brawl. You can’t be too methodical.

Sergey is nothing if not methodical. Right away, during the first game, he got down on the clock, coming within minutes of losing on time. While Magnus threw out move after precise move, Sergey hemmed and hawed, his face in his hands. Although the game ended in a draw, Sergey walked away pale. A crowd of thousands stood outside in sub-zero temperatures in Moscow, flooding the Red Square, watching the tiebreaks on huge monitors. They can’t have enjoyed game two. From the very beginning, Sergey was on the defensive — his pieces were tripping all over each other. Chess computers, analyzing the game in real time, indicated that it was all but over. Spectators in NYC, watching the game from outside the soundproof shark tank, waited for the killing blow. And waited. And waited. And somehow it never came. Sergey annoyed Magnus as much as possible — ducking and dodging and refusing to be beaten easily — and eventually made the game a draw. The fans were standing around with their jaws hanging open, including Irina Krush, seven-time American women’s cham- pion. “It’s kind of hard to believe what happened,” she told me. “I definitely thought Magnus would take it in the four-game rapid. It’s difficult to make a prediction now, since that was such a painful, painful missed opportunity.” A contingent of Norwegians were experiencing a great deal of psychological disarray. Commentators wondered whether Magnus could make a comeback.

The question was answered decisively in round three, where Magnus handcuffed Sergey, then tickled him until he squirmed. Eventually, very low on time, under immense pressure, he made a bizarre move that lost instantly.

Now, Sergey was in a must-win situation. He opened the game with the Sicilian Defence, which is what you play when you can’t settle for a draw — when you need a dangerous game. In the Sicilian, both players are continually attacking down both flanks. Sergey played aggressively from the very beginning. But he was rewarded by being beaten picturesquely, with a beautiful finishing blow from Magnus — he parted Sergey’s pawns by sacrificing his queen, then reached through the opening and killed his king. Match Magnus.

At the press conference, while the Norwegian was queried about why he wore NBA socks during the final game, Sergey smiled meekly, restraining tears. A little bald man with a moustache gave both players medals. The prophecy was fulfilled: Sergey’s scholastic powers were trumped by Magnus’s sixth sense. The king, to paraphrase The Wire, stayed the king. And so it would continue, indefinitely.

Or maybe not. Sergey had come really close. For a precious moment, after that eighth game, he had Magnus on the ropes. Maybe he just didn’t think he could beat Magnus — how dare he do such a thing — and psychologically collapsed. Perhaps he succumbed to the fatalism that creeps into my worldview as well. This idea that we’re down here, we mere primates, and can maybe be exceptional in our small, foolish ways, but that guys like Magnus are on some other unreachable plateau, and we can only watch them with a kind of sad wonder. Anyway, I had an interview set up for the following day. I wanted to hear Sergey say that he’d come back next time, that he could rise above and kill it. Although, as a reporter, I should’ve been properly agnostic about his potential responses, I was also a dude wondering about his place in the universe. I wanted to see passion in Sergey’s eyes — a continued will to transcend.

But when I woke up, I received the following email:

“Hi sasha

Apparently he has already flown home…”