Know Your Designers: A Q&A with Frank Stephenson, Legendary Designer for McLaren, Ferrari and Mini

Frank Stephenson is the prolific designer who brought back the legendary Mini Cooper in 2001, and established the look of McLaren Automotive with the MP4-12C, P1 hypercar and others. He also found time to lead Ferrari’s design department, creating the F430 and FXX, and pen the Maserati MC12, and even draw BMW’s first ever SUV, the X5.

Oh, and recently, Stephenson has been doing some of our favourite, must-watch YouTube videos in which he honestly appraises and breaks apart the design of vehicles like the Tesla Cybertruck, BMW 4 Series and Ford Bronco. Prolific is an understatement.

We caught up with Stephenson at his stunning home studio in the Buckinghamshire countryside. We were only meant to talk for 30 minutes or so, but it ended up being well over an hour. Anyway, we think you’ll enjoy what he has to say on jeans, watches, cars, good design, the Mini, how supercars are like haute couture and one terrifying moment at McLaren.

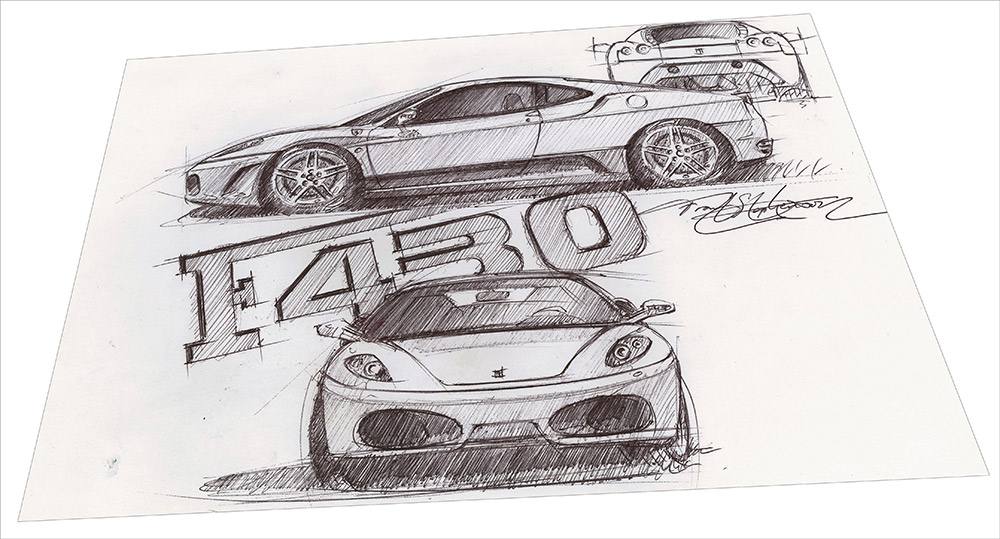

A sketch of the Ferrari F430.

A sketch of the Ferrari F430.

First thing’s first. What are those model cars on the shelf in your studio, and why those particular cars?

On that shelf I’ve got most of the cars I’ve worked on: a 2001 Mini, Ferrari F430, FXX, Maserati MC12… On the other shelf I’ve got some of my favourite racecars: a Maserati 250 F, a sharknose Ferrari, the Tyrrel P34 six-wheeler, the McLaren MP4-4 as driven by Senna. There are my Ducati models too, my Batman figure, and a Jaguar XK 120 and 150. I’ve got the Leaning Tower of Pisa too, but I couldn’t stand that it was leaning so I put it straight. And I’ve got some whisky to keep me going, and coffee too.

Wait, is that also a longboard and a hand grenade in the background?

Those are my vitamins! I keep my vitamins in the grenade. And, yes, that’s my longboard too.

You’ve designed not just cars but also smaller consumer products and even a yacht. Any parallels between furniture or industrial design and automotive?

Funny thing about being a car designer is you’re pretty much trained to design anything. A car designer is a glorified product designer because we end up designing door handles, we’re designing the wheels, the pedals, every button you have to touch, the instrumentation. If you can do that you can do furniture, fabrics, watches, anything.

Speaking of watches, we can’t help but notice that enormous orange one on your wrist. What’s the story there?

That is a watch I’m very proud of. It’s a Rebellion; they have their own Le Mans endurance racing team. Rebellion is one guy whose passion was to start a watch company. This particular watch is a special edition. Basically, they asked me if they made a watch the way I wanted, would I wear it? And, well, yes. So, this is the FS edition, one of one. It’s got some really interesting colour breakup: black on that side, orange there. You could take this off and if you hit somebody over the head and it’d probably give them a concussion. But, I like watches where you know you got a watch on your wrist.

Stephenson’s reborn Mini

Stephenson’s reborn Mini

Probably the 2001 Mini is your most ubiquitous design. It relaunched this famous brand. But, for those of us too young to have driven the original, why was OG Mini become so brilliant?

When the car first came out in ‘59, it didn’t really take off. It was basically an answer to the crisis in Suez, Egypt. The revolutionary idea that [original Mini designer] Alec Issigonis had was, let’s make this really tiny car and turn the engine sideways. Doing that allowed this very, very tiny car to carry four adults. It looked really strange. And, people weren’t really willing to go for something that was so technically revolutionary. Only when a guy named John Cooper – a racecar team owner, engineer and basically one of the geniuses of the era – came along in ’63 and saw the potential of the Mini as a racecar did it really take off. They went to the Monte Carlo rally and won in ’63, ’64, ’65, walking all over the big names. So, this little got got this giant killer reputation. Race on Sunday, sell on Monday – that’s what happened I think. It became a vehicle for families to go up and down the countryside for not much money. Pop stars and models bought it. It became the car to have all over England and even Europe. It became classless.

What a nightmare trying to reinvent that, to create a new Mini for the 21st century. No pressure, then.

My intent was to keep [the 2001 Mini] as small as possible. The car had to grow – people are bigger and require more space, and crash safety regulations have obviously evolved. It was a risk making a small car for the US market. But, it was a blast to drive. You’re a zombie if you don’t enjoy driving this car. It’s a modern interpretation of an iconic design. It was marketed at the cool crowd. I remember BMW saying, lets try to sell 20,000 Minis in the first year in the US. They did, easily. Afterwards, the Miami dealer called me up and said you guys are complete nincompoops; you’ve could’ve sold 20,000 easily here in Miami alone.

What’s the hardest thing about designing a new car these days? I mean, Alec Issigonis was almost completely free from regulations and rules when he penned the original Mini.

I think the best designs just naturally come from one philosophy, or one person. They say that design is a team effort, and obviously it is, but if you get one person that can just make all the decisions it’s going to tend to be a cohesive design. That’s how the 2001 Mini happened. But, that doesn’t happen all the time. I’ve been in many projects where everybody wants to have a say, because everybody’s a designer. You get the finance guy coming in and saying ‘Well I don’t know about that’ and I’m thinking, what the hell does he know about design? I don’t go into his meetings and tell him that I don’t like the look of his numbers.

A riverboat Stephenson designed for himself.

A riverboat Stephenson designed for himself.

Who is the GOAT? Are there any designers or architects who inspire you?

Well, I don’t want to sound crazy, but I get most of my inspiration from a guy that’s actually been dead for a while. He did a lot of different designs for a lot of different disciplines and everything he did had a common thread, which was what we would today call “biomimicry” – the influence of nature in design. Maybe you already know who I’m talking about: Leonardo da Vinci. He was just as good of an architect as he was an inventor as he was a designer as he was an artist. For my overall design inspiration I don’t go to anybody too much in architecture or furniture or fashion. I typically find those design professions trendy: the designs come out, they make a huge impact, and then something new comes along. Whereas the science of biomimicry, or bringing design influence from nature into your design, tends to give you that same thing that happens in nature, which is long lasting design appeal. Nature doesn’t really do trendy.

What’s in your garage now?

I’ve got a Jaguar E-type, a series one. The funny thing about that car is that it wasn’t actually designed by a car designer, it was done by an aerodynamicist named Malcolm Sayer. (The guy couldn’t draw if his life depended on it. But, he knew about aerodynamics.) And, then I’ve got an old, old Land Rover Defender. It feels like your favorite pair of worn out jeans that you put on even though they’ve got holes in them, you know? Like jeans, it’s classless, you can drive it anywhere like you can wear jeans anywhere. Actually, at McLaren, they wouldn’t let you wear jeans inside, at least when [ex-CEO] Ron Dennis was there.

Stephenson introducing the McLaren MP4-12C in New York.

Stephenson introducing the McLaren MP4-12C in New York.

How did you end up working at McLaren Automotive?

I was working with Ferrari, Maserati design, as head of design and for FIAT group, which also includes Alfa Romeo. In early 2008 I got a call from Ron Dennis at McLaren telling me that they’re not sure how Formula One’s going to go. It might go downhill and then they wouldn’t have a company left. So, he wanted to build a road car company to support and add to McLaren Racing, like Ferrari has always had. I came up to McLaren from Italy and had a great conversation with the team and decided: Yes.

What was it like in the early days, kicking off a brand new supercar company?

It was small, seven or eight of us that really ran McLaren for that exec level. I was responsible for design. The guys who were responsible for purchasing or manufacturing, they were all very good at what they did. That passionate small group of guys were the ones that sort of kicked off McLaren road cars with a bang. Cars started flying out of McLaren like crazy.

The first of the new McLaren’s, the MP4-12C, has aged beautifully, but when it came out some people said it should’ve looked more wild and crazy.

The first impression, you only get that chance once. We didn’t want to make a Versace, an over the top type design that looked extravagant, and we didn’t want to make a deadly simple, very traditional, English-looking, very correct product. And that fine balance, that was basically what the 12C was. It had a lot of influences from biomimicry again.

Then came the McLaren P1, this wild hybrid hypercar the likes of which the world had never seen. Admittedly, when we first saw that car, it was like: what is that?

It had to have that wow factor, it was haute couture. In fashion, when you do haute couture you’re out to shock; you’re not out to sell a lot of them. You’re trying to show what the company can do at an extreme level. Ron Dennis never wanted to come into the design studio to see the development progress. We had a year to do it, but he said just ‘show it to me when you’re ready and I’ll let you know if I like it or not.’ That day came and we pulled the cover off and he stood there, his jaw dropped. I remember his first question; I’ll never forget it. “Where’s the front and where’s the back?” I was like, yeahhh – of course I was trembling a bit. That car was all about shrink wrapping. There’s no fast animal in the world that has a lot of fat on them; they’re shrink wrapped. It’s about reducing visual weight. The P1 looks fast just sitting there – that car definitely goes to the gym, two times a day, seven days a week.

McLaren P1

McLaren P1

McLaren P1

McLaren P1

When did you fall in love with cars? Was there a single moment or what?

It was March 19, 1969. Seriously. I was walking down Boulevard Muhammad the Fifth, a big boulevard in Casablanca. I was walking with my father, a very sunny morning, a tree-lined avenue. I was nine years old, and I saw this Jag E-Type, series one, and I just froze. I mean, I was passionate about cars but I just froze. I remember not wanting to leave. I was just sitting there looking at this E-Type, this metallic light silver-blue colour. I couldn’t believe that something that beautiful could be just sitting there, not in a museum. It’s like seeing the Mona Lisa or something in the street. My father, after about 10 minutes, he had to drag me away. I was hoping if I stayed long enough somebody would come and start it up.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.