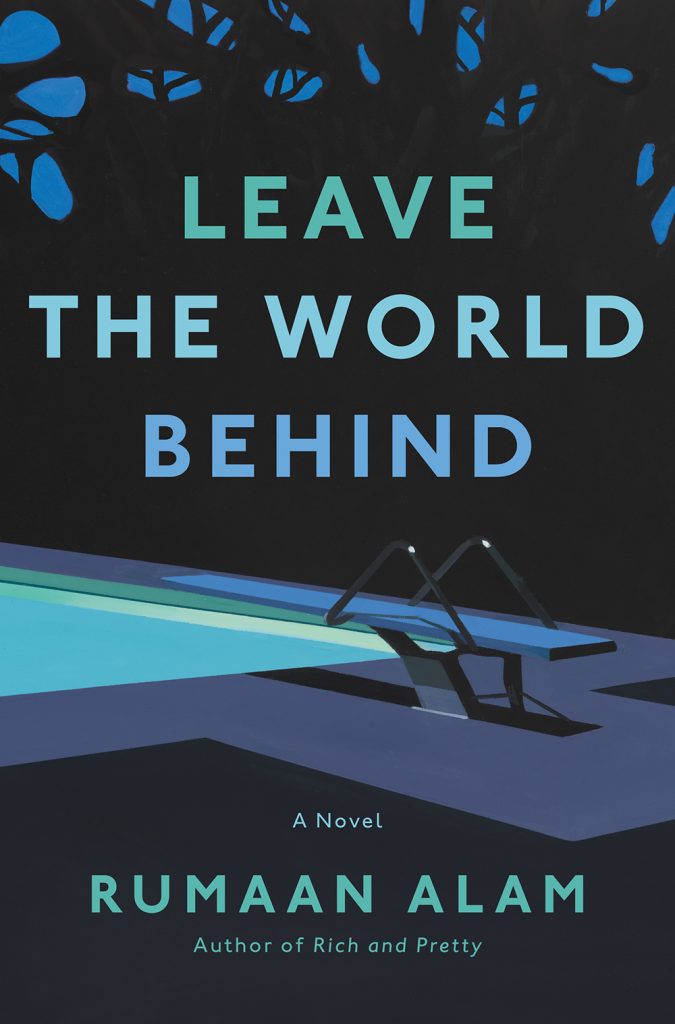

Author Rumaan Alam on Heroism, Masculinity, and How We Behave in a Crisis

Rumaan Alam’s third novel, Leave the World Behind, is a timely example of how we cling to the rituals of domesticity in times of chaos. A Brooklyn family has gone for a summer vacation to a remote house on Long Island. For the first hot, languid day the family settles in, Alam’s prose is noticeably rich — a tool he says is meant to unsettle the reader. Late one night, a knock at the door brings two strangers with news of an unknown catastrophe that has caused the Internet, phones, and cable to go down. As days go by, the family must integrate with these strangers — a thoroughly contemporary examination of class, race, and how we navigate survival without technology. The once-charming and rustic house becomes the perfect environment for a kind of claustrophobic paranoia to set in. From his home in Brooklyn, Alam and I discussed the current state of literature, heroism, and technology.

MG: The most remarkable part of reading Leave the World Behind was the way you developed all the characters, and the use of the omniscient narrator, so the reader knows what everyone’s thinking. How were you able to create a distinct voice for each character?

RA: For the first several drafts of the book, the reader was watching them from a remove, and my editor said it was annoying because the characters don’t know what’s happening and neither does the reader. The solution was to change the perspective so that the reader knows everything that’s happening, and everyone’s interior thoughts. I wanted to work in that way where the story knew all the information and just wasn’t sharing [all of] it with the reader or with the characters. It’s something I came to in revision. I think five or six drafts into the book.

I loved the way the characters gave into thoughts that they felt guilty about. “Maybe this is racist. Maybe this is something I shouldn’t be thinking.” We lose out on that a lot of the time because we want characters to have a certain type of politics or to be…good people. I think that’s so untrue to life.

People think ugly things. They think bad things. It’s part of being alive and part of being in a society. Yes, people are flawed. I see people negotiate with that all the time. It’s just part of the bargain of being a human, and I think it’s okay to acknowledge that. I don’t think it makes you a bad person or an unlikeable character to have a fleeting self-aware thought that’s racist or sexist or whatever. People do it all the time.

The idea of likeable characters feels so dry. There’s this urge to need likeable characters in novels in order for readers to latch onto them.

I’m not sure that novels ought to aspire to a feeling of reality, because they’re not real. I think there’s a certain kind of artificial quality to fiction that we sometimes try to pretend doesn’t exist. I think that we do ourselves a disservice. In terms of whether you care about the character or not, I find that the most pernicious way of talking about fiction. It’s really crept into the cultural conversation.

Don’t you think that this line of critique is so particular to literature? No one cares if the same is true for TV shows or films.

Absolutely. In fact, we’ve valorized television that is about bad people. All of prestige television is just television about people who are terrible.

I wonder if it’s because you’re more in someone’s head in a way you can’t replicate in other media. If it doesn’t match up to how someone sees the world, there must be something wrong with the novel.

Yes. Absolutely. It’s like [this viewpoint] prioritizes the reader’s experience of the world and says, “Is this correct or incorrect?” Rather than taking the book as it is and saying, “Well, obviously this is not real. Obviously, it’s pretend.” You’re making something, you’re building a construction to make a point. If readers want to reject that because it’s too outlandish or this would never happen or whatever, then they misunderstand what it is to read a book.

I try to talk about writing as you would talk about fine art. A person who’s an artist started out by learning how to draw silhouettes and shadows, in the same way the writer learns to construct sentences, but afterwards you’re supposed to diverge and go off into your own style.

Absolutely. There’s no power to Rothko or Pollock without an ability to understand that Pollock and Rothko also knew how to draw and capture perspective. They rejected that in service of a style that mirrored how it was they wanted to see the work that they were doing. What you heard from critics contemporaneous to the development of modern art or abstract art was, “Oh, well, this is just child’s scribble.” That’s not what it is. It’s an active rejection of something in search of something else. It’s style. I think that’s a really simple word for it. I think that your book [Happy Hour] is very stylish; it’s a very stylized book. It’s describing a contemporary urban youth that doesn’t have access to richness and money and polish but insists on it nevertheless. There’s something funny about that. To write about a contemporary young woman stumbling through contemporary life, but to treat her the way that Edith Wharton would have treated her, it’s a stylish endeavour. It’s fine if you don’t like it. That’s fine, but to not understand that feels like a mistake to me.

A lot of the films I love were once plays. What helps those films is the fact that they’re stuck in one setting, which your novel also is. There’s the feeling that you’re trapped. Whenever the reader is let in on some information that the characters aren’t, it releases some of that suffocation. I feel like knowing that information made me feel much less generous towards the outbursts of the characters. Like with the mother, Amanda, especially. I kept thinking, “I can’t handle her. She doesn’t know what’s going on.”

She doesn’t know. You either pity her for her not knowing or you’re frustrated because you’re like, “Well, don’t you

see what’s happening?” Then there’s no way in which they could really see what’s happening. That, to me, is what this moment has been like, politically in [America]. If you think about the ways in which we dithered over the last president’s violations of political norms, we spent so much time fighting about this dumb stuff while we were taking infants from their parents. It was like we were totally distracted. With the remove of history, people will be like, “Didn’t they know? Why weren’t they marching on the streets? Why weren’t they doing anything?” I don’t know how we answer that. It’s like, well, we did know and we still didn’t really do anything.

That’s what’s interesting about reading your novel right now too. Humans have an instinct to continue living in whatever form. Even when we are currently in lockdown, in a pandemic, somehow we have to continue working and doing all the normal tasks. We still have to do these things while we’re under extreme stress from a worldwide disaster.

People don’t necessarily care. It’s a very strange condition of living right now where it’s like, we’re really connected to the entire universe. Like, if the Prime Minister of India was assassinated right now while we are on this phone call, we would both get an alert on our cellphones telling us that. Would it mean anything to us? Would it feel earth-shattering or would it feel removed and abstract? All this information is always coming at us and we can’t really process any of it. We just continue doing the same things we’ve always done, which is make dinner and, I don’t know, try and work out on your bedroom floor, or whatever it is you do to get through. That seems to me what we’re all doing, is muddling along.

There was this one line where someone thinks, “People drop dead, but you still need to eat dinner.” It felt so true. Towards the end of the novel, I kept thinking that that line is the all-encompassing idea of what life is like and how we are currently living right now. In what ways do you think it’s dangerous to be tethered to technology?

That’s what the book is fundamentally about. It’s not a book that’s describing our reality, but it’s a book that hopefully is getting at what it feels like right now, emotionally [and] intellectually. I’ve had a cellphone for 19 years, but it was only in the last seven or so that the cellphone supplanted the camera that I have. I remember a time when we had a GPS for the car that was not my phone, but now that’s just the phone, so everybody uses that. We don’t know what it’s doing to our brains. We don’t know what it’s doing to our evolutionary progress.

There are struggles with masculinity too. Especially with the character Clay. There’s this deep urge from the men of the book to want to be seen as strong, as leaders of a household.

When we talk about World War 2, we love to tell the stories about the everyday heroes. The people who hid their neighbours in their basement. It’s very hard to talk about the people who were like, “Oh, well. They’re taking my neighbours away. Life goes on.” I didn’t go to the airport and demand that they let people from Yemen into the country. I didn’t go to the border. I didn’t do anything. Most people I know didn’t do anything. That’s how people react. We think we’re all heroes, but I’m not sure that we really are.

It takes such a specific type of person. I remember once, I was sitting in a park in London, and a fight broke out. It was this hot summer afternoon, and there were so many people in the park that day — think McCarren Park in the summer. The man I was with got up and ran towards the fight to intervene. I remember being so shocked by this.

Yes. It’s a very specific response, and also a very masculine response. I’m going to take care of this situation. I’ll roll my sleeves up and take care of this situation.

The novel is really asking us, when it comes down to it, who are you in times of catastrophe? How can you really guarantee what your response would be?

We just live through it, because we’re living through a catastrophe right now. Most of us, what we did is we went grocery shopping and bought new gym clothes on Amazon, and free weights, and decided to work out at home instead of going to the gym. That’s what we did. To talk about that character as being unlikeable or likeable misses the point entirely. It’s like we’re not living to be likable or unlikeable. We’re just trapped being ourselves.

Lead Image: David A. Land