Halt and Catch Fire: A Conversation with Joe Hill

There was a time when, if you wanted to praise a television show, you’d compare it to a book. The Wire, for example, was said to be like a Great American Novel: richly layered, sprawling, complex, and deeply human. And while all that is accurate, the comparison felt defensive. Sure, you binge-watched season four in a week, but it wasn’t a waste of time any more than reading Dickens would have been a waste of time.

We’ve moved past that. Great TV is its own justification without the desperate comparisons to highbrow literature. Actually, when you consider television’s quality (and ubiquity) and measure it against the declining popularity of the printed word, the metaphoric pendulum has swung the other way. It’s time to reverse the comparison.

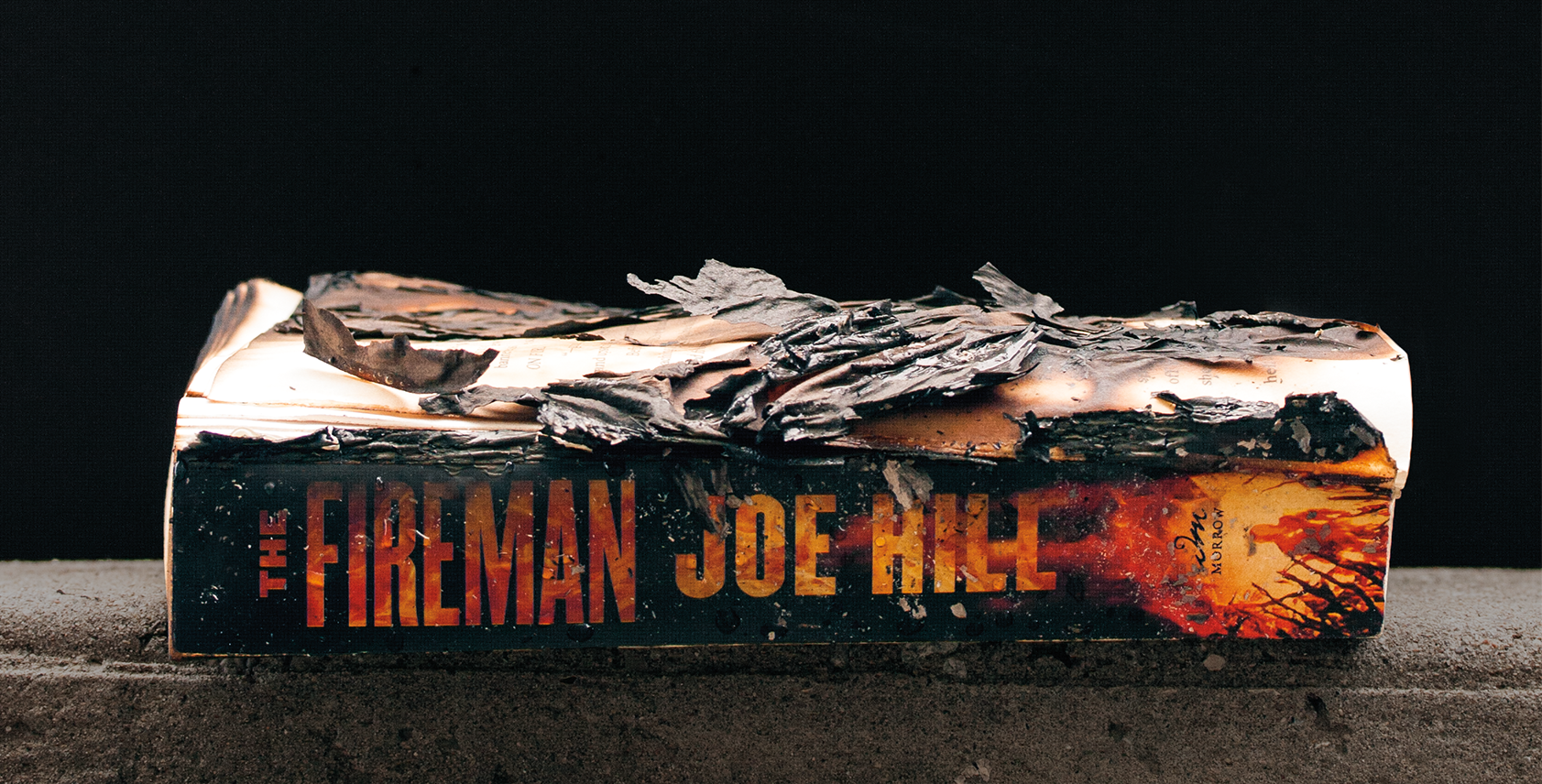

So, here goes: Joe Hill’s new novel, The Fireman, in which a spore-based epidemic causes spontaneous combustion in the infected, along with the inevitable deterioration of society, is like reading the best never-produced series from AMC (or HBO or Netflix). Like good TV, it’s propulsive and intimate. The core characters revolve around a sympathetic, fully realized protagonist — Harper, a pregnant nurse — who is taken in by a community of infected people who seem to have a way of keeping the spore from burning them up. There are small subplots, but nothing tangential or discursive, much like a controlled, disciplined television B or C plot.

All of Joe Hill’s work is like that. He’s a masterful storyteller, expert at crafting and controlling plot in a way that feels distinctly contemporary, as if he’s been trained by Twitter and TV recaps to know what leaps of imagination would be too great, what twists would be too telegraphed. Everything seems real, as if it’s been fact-checked by an easily dismissive viewer. Or, in other words, by a modern fan. People say his father, a fellow you might have heard about named Stephen King, is the quintessential storyteller — and he is, or at least the most famous — but Hill’s works are somehow tighter and more urgent, even if they aren’t any shorter.

It’s not just that Hill’s writing feels younger (in the best way possible); it’s that — and this could be paperback blasphemy — sentence for sentence, Hill may be a better writer. Keener observations, smoother metaphors, generally more “literary,” while still pumping out the juiced-up plot. As a Gen-Xer, Hill is comfortable writing in the space between pulp and highbrow, so much so that the distinction becomes meaningless.

In the hands of someone less comfortable, The Fireman could have become a pretentious parable, as narratives about disease often are. Hill ensures that the epidemic is scientifically plausible so that the supernatural stuff, when it comes, is grounded in realism. The spore feeds on the stress and fear of the infected. They burn when they are most afraid. It manages to raise questions about the dual nature of community: they can be safe havens on the one hand, but quickly turn tribal and aggressive on the other. The fact that we’re dealing with an enemy, so to speak, that leads to something as primal as fire, which can warm or burn, is spot on.

If Hill wasn’t as interested in that issue, if he just wanted to tell a gripping story about survivors surviving, it could have become like his father’s famous epidemic/apocalyptic novel The Stand, which is a ripping epic but is as morally complex as a bible story. The Fireman is safely both, or neither. It’s a page-turner that compels, seduces, and ultimately rewards a thoughtful reader.

It’s good TV.

•••

JOE HILL: I never would have predicted of all the ’80s action stars that Bruce Willis would have the best career, and be the most fascinating to watch. I think that you could easily program a weekend Bruce Willis Film Festival that would be mind blowing.

The Die Hard sequels are really like the sequels to Jaws. Just the idea is deeply misguided. I see now that they are plotting a Die Hard prequel. Someone quipped on Twitter: Isn’t Die Hard the Die Hard prequel? Isn’t that how John McLean became John McLean?

SHARP: Maybe it’ll be a chamber piece where we see his marriage falling apart and it won’t be an action movie at all.

That would be kind of great.

That’s the prequel. We find out why he and his wife are fighting and why she moved to LA in the first place.

I’ve been watching the Netflix Marvel Universe shows. One of the moments I loved in Jessica Jones is when she’s sitting with Luke Cage, and he says, “Were you born with your powers?” And she says, “No. Accident.” And she says, “Where’d you get yours?” And he says, “Experiment.” That’s it. We don’t get anymore.

I like Jessica Jones too, because so often sexual assault is just there to create the female hero. This one, because it extended beyond a woman, it was a little different, and I appreciated that. They talked about feelings of violation and feelings of being used, but it wasn’t just towards women.

This is sort of a core belief with me. One of the reasons people turn to fantasy or science fiction or horror fiction is because there is subject matter that is very emotionally fraught. There are questions that don’t have answers and there are subjects which are difficult and painful to face. But art can create a safe playground where those subjects and questions can be wrestled with, and those emotionally fraught issues can be examined safely. If the artist does his or her job well, they can talk about something like sexual violation. The subject itself is like a radioactive isotope. An artist can use his art as a pair of lead-lined gloves to pick that up and turn it over and have a look at it.

Jessica Jones succeeds because it transmutes sexual assault into something different, which is mind control. They have been able to look at Mr. Purple and the way he uses his powers as their metaphor for sexual assault, for violation, and for the trauma that follows it. I think that’s tremendous. It’s always exciting when someone finds a way to tackle a subject that is difficult and do it in a way that might be positive and helpful for people who maybe don’t want to address that subject head-on in everyday life. But in the safe playground of fiction they can examine that.

What authors do you think do that well?

In some ways that is the essence of the job, at least when you’re talking about fiction that is fantasy and supernatural and horror. Someone, at some point, said, “Every ghost story is an attempt to wrestle with this idea that our existence is limited and that everyone dies, and what happens then? What happens when you’re gone?” Ghost stories have always been, going back to before printed literature, a way to wrestle with this subject. Does our information erase when we die? Or does it linger in some form?

I think it does linger. Your personality doesn’t just exist in you. You are one person with your friends. You are another person with your parents. You are another person with your co-workers. Little bits of your personality are stored off-site, in them. In a way, when someone dies, their personality is still hanging around, because little bits and pieces of it have been copied off into other people.

The other thing ghost stories are always about are how the past leaks into the present. We’re never ever really able to escape ancient damage. Things that happened fifty years ago still have power now.

Don’t we see that to a degree in the white supremacy movement that is backing the Trump campaign? It’s clear that the country is still haunted by its long-standing fight over civil rights. All those ghosts are still walking with us, whether we like it or not.

Let’s start with The Fireman, because that’s what’s relevant now. This is one of those basic questions, but what was first thing you decided you wanted to do? Did you want to do an epidemic novel?

I’ve wanted to write about spontaneous combustion. I’ve wanted to write about spontaneous combustion for years and years. As a child, I was fascinated with it. I lived in fear of the idea that I might suddenly ignite and burn to death in front of my classmates or out on the playground. It was a troubling possibility. Like being bitten in two by a great white shark.

Or tornadoes. I was scared of tornadoes as a kid.

I’ve always been a little more excited by tornadoes. I feel like I have the personality that I’d be willing to go with the tornado chasers. I have this crazy notion that it will never turn towards me. “I’ll be fine! I’m getting some really good footage.”

But spontaneous combustion could.

But spontaneous combustion seems like a more realistic fear than tornadoes. I had an idea to write a story about spontaneous combustion. I had the opening scene for the book in my head for almost a decade: the man staggering drunkenly across the playground behind the school and then falling to his knees with smoke pouring out of the sleeves of his coat and then bursting into flames. I knew that was where the book began.

I think I thought it would just be a short little novel when I started. It wound up being longer than NOS4A2. Hopefully, if I did my job well, though, it won’t feel long.

That’s really 80% of the job. It’s like building an aircraft where you want to make it as lightweight as possible. You want to make it so that it feels authentic and true and you can identify with and care about the characters, but you really don’t want a single ounce of excess weight, so that the reader is buckled in and the thing takes off and gets up to Mach 1 as fast as possible.

I have this friend who’s an author and when he writes his literature books he uses his real name, Craig Davidson…

I know Craig Davidson! Did he write Rust and Bone?

Yes, that’s him. When Craig writes his horror novels, his publisher, or his agent, or someone makes him change his name.

What’s his horror novel name?

His horror novel name is Nick Cutter. In Canada, at least, it’s not at all a secret. When they write about Nick Cutter they say: “Nick Cutter, who’s also Craig Davidson and is nominated for a Giller…” So, I know why you go by Joe Hill and not your real name. I am curious if there is any kind of freedom that comes from adopting a moniker that isn’t your real name.

There was real tremendous freedom at the beginning, which was when I needed it most. It was in college that I decided to drop the last name. I’ve talked a few times about why I did. The biggest reason was I didn’t have a lot of self-confidence and I felt I had a lot to learn. I was afraid if I wrote as Joseph King, I might get published because I was Stephen King’s son and that people would read the book and it would be terrible and they’d say, “I know why he got published, because his dad is someone famous!”

I didn’t want that to be my fate. And then all those readers who bought the first book because my dad was famous, wouldn’t buy the second book because the first book sucked. It was terrible. It was unreadable. And so I didn’t want to be in that position. That’s why I chose the pen name. I was able to maintain it for about ten years. During which time I didn’t succeed in getting a lot published. I wrote four novels that were turned down. I wrote a trickle of short stories that I was able to sell. I did learn my craft. My big breakthrough was when I was able to sell an 11-page Spider-Man script to Marvel comics. That was my great triumph under the pen name.

The other thing is, when I decided to drop the last name, I also decided I was going to write mainstream fiction. I wasn’t going to write horror or fantasy. So I wrote the kind of stories I thought they published in the New Yorker. I wrote about divorce. I wrote about mid-life crises. I wrote about raising difficult children. Most of those stories were really dull. They didn’t have any interior spark.

Looking back now, it’s no surprise. I hadn’t been divorced, so I didn’t really know anything about that. I was writing these stories in my 20s and early 30s and I hadn’t had a mid-life crisis, because I hadn’t reached mid-life. I was just starting out as a father, so I didn’t have a lot to say about children. It was artificial and fake. At some point, after two or three years of writing those kinds of stories, I had this idea of writing a fantasy story. I suddenly realized it would be okay to write it because I wasn’t Joseph King. I was Joe Hill. No one knew anything. No one had any idea who my dad was, or cared. The pen name became a permission slip to write the kind of fiction I actually wanted to write.

As a kid, growing up, I had friends who had subscriptions to Sports Illustrated. I had friends who subscribed to Rolling Stone magazine. The magazine I subscribed to was Fangoria, which was this ghastly horror magazine. That’s what I really liked. I didn’t read John Cheever or John Updike or Alice Munroe. My favorite writers wrote comic books. I read Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore and Frank Miller. That was the literature I was steeped in. It may be stretching the term “literature” to call some of the Marvel and DC output in those years literature, but I felt it mattered. I loved those stories. I still think Alan Moore’s fiction and Neil Gaiman’s fiction, in all the different forms they’ve written in, will outlast a lot of the New Yorker writers who were being published at the same time.

The pen name did give me this terrific freedom to find the subjects I actually cared about, which weren’t always independent of the kind of things my dad wrote. No big surprise. I’m a big Stephen King fan. All my favorite horror films, I watched with him. We love all the same films.

You want to find subjects that excite you. You want to write something where the story kind of has a life of its own.

I don’t want to get too carried away with the idea that stories have lives of their own because there is a “grind it out” quality to every writer’s life. It’s not magic every day. It’s not magic most days. You can fumble through the fog and find your way to the next piece and then work on that piece until it shines, and then move on to the next piece. Sometimes the fog breaks up a little bit and you’re having fun.

I was curious about Dragonscale, the disease you invent in the novel. How much did you want it to have some metaphorical value? The kids in the novel compare it to social media. There is also fear generally, and that’s the real enemy.

Fear burns you up.

How much was that on your mind that you wanted to have an analogy or parable component to it?

This brings us back to where we started the conversation. I do think that with the fantasy novel or horror novel or science fiction novel, there’s the specific matter of the plot and the characters, the entertainment value of seeing heroes you care about in desperate situations. But I also hope that the horror novel will be about something more than itself, that it will ask some interesting questions. It doesn’t necessarily have to have answers. Maybe sometimes it’s better if it doesn’t. If the questions in the book can be answered, you almost wonder why you’re writing fiction at all. Shouldn’t it be non-fiction? Fiction is really a place to explore subjects that can be experienced, but there’s no “two plus two equals this.”

I did want to write about how communities can destroy themselves. How communities can provide shelter and love and affection, but can also be tribal and self-destructive and destructive to people who disagree with them. That can be troubling. That’s true whether you’re talking about a real-life community or a digital community. People are coded to be awfully tribal. It’s not our most flattering trait as a species.

I also wanted to talk about how when you’re up against it, what can you turn to use as a tool to survive? What can be counted on? I looked at marriage. My heroine, Harper, has this marriage that isn’t terribly healthy and completely disintegrates in the face of this crisis. So marriage doesn’t pan out.

Then Harper finds her way to Camp Wyndham where there is a community of faith. It’s not a Christian faith. It’s not a religion we’re familiar with. But it is a religious community in its own odd way. That also provides shelter and comfort for a while, but that also turns out to be a poisonous and dangerous place.

I guess what I think is, in moments of crisis, the one thing you can count on is character. Character tells. People who are good, decent and empathic stubbornly continue being that way, even when things are bad. Character traits tend to be a magnifying glass in crisis. The person who is a little selfish and judgmental and a little panicky becomes more so under the amplifying source of crisis. If you’re a little paranoid, in a crisis you’ll probably be a lot paranoid.

This is the second novel you’ve written with a female protagonist. In it, she talks a little about how annoying male writers can be because they want to control a puppet woman.

Exactly.

It seems important to you that your heroines have agency, are fully fleshed out and, especially with NOS4A2, have some flaws.

Talking about the Marvel movies, there has been a lot of frustration with that Black Widow character. Mark Ruffalo said a wonderful thing. He said the problem is there isn’t enough women. The Black Widow character has to represent every woman, and it almost destroys any chance of her having a coherent personality. The only solution is to cast more women to have more female heroes, too. I think genre fiction, especially, often really suffers from just having one girl in the lifeboat.

Then again, there is a strain of horror fiction that has always been very feminist and very inclusive. Part of that is because, to be an outsider in society, to be disenfranchised, to not be a white guy, to be in that kind of slightly more disadvantaged position, puts the hero in a precarious position just to begin with. Horror and fantasy often tends to side with whoever looks like the biggest underdog.

When you’ve got your imagination switched on and you’re writing a novel, it’s not terribly helpful to be too anchored in your gender or too anchored in your sexuality. You have to be fluid in your imagination or you won’t be able to think your way past your own genitalia and your own preferences. At least while you’re playing the part, at least while you’re in the story mode, you have to do your best to imagine your way into that other body and that other skin. Maybe no one is ever completely successful at it, but you get no bonus points for not trying.

Except for Heart-Shaped Box, in all your novels, there is a moment where you make me cry, you son of a bitch. I was curious if pathos — the ability to make us feel something like that — is it as intentional to you as trying to scare us? Do you work as hard at both things?

Actually, I think I care a lot more that you will be moved than that you will be scared. When I do write a scene that is effectively scary, I’m always surprised to find out afterwards that it was. It’s rarely a conscious thing.

I didn’t know Heart-Shaped Box would be effectively scary until people started to tell me me that it was. I thought it would be exciting because he would have this ghost on his tail and you weren’t sure if he would survive. I didn’t know what would scare people and what wouldn’t until after the fact.

When something is moving, though, do you have a better idea of whether it will be moving or not?

I think there has to be human stakes, always, in a story, in order for us to care. I think that that’s important. I think that also it can be a release to read a story or see a movie that makes you tear up a little bit, because a lot of times we don’t allow ourselves to be sad about good things that happen. We go to that safe playground of art where we’re allowed to feel things you’re not allowed to feel in the average run of your day.