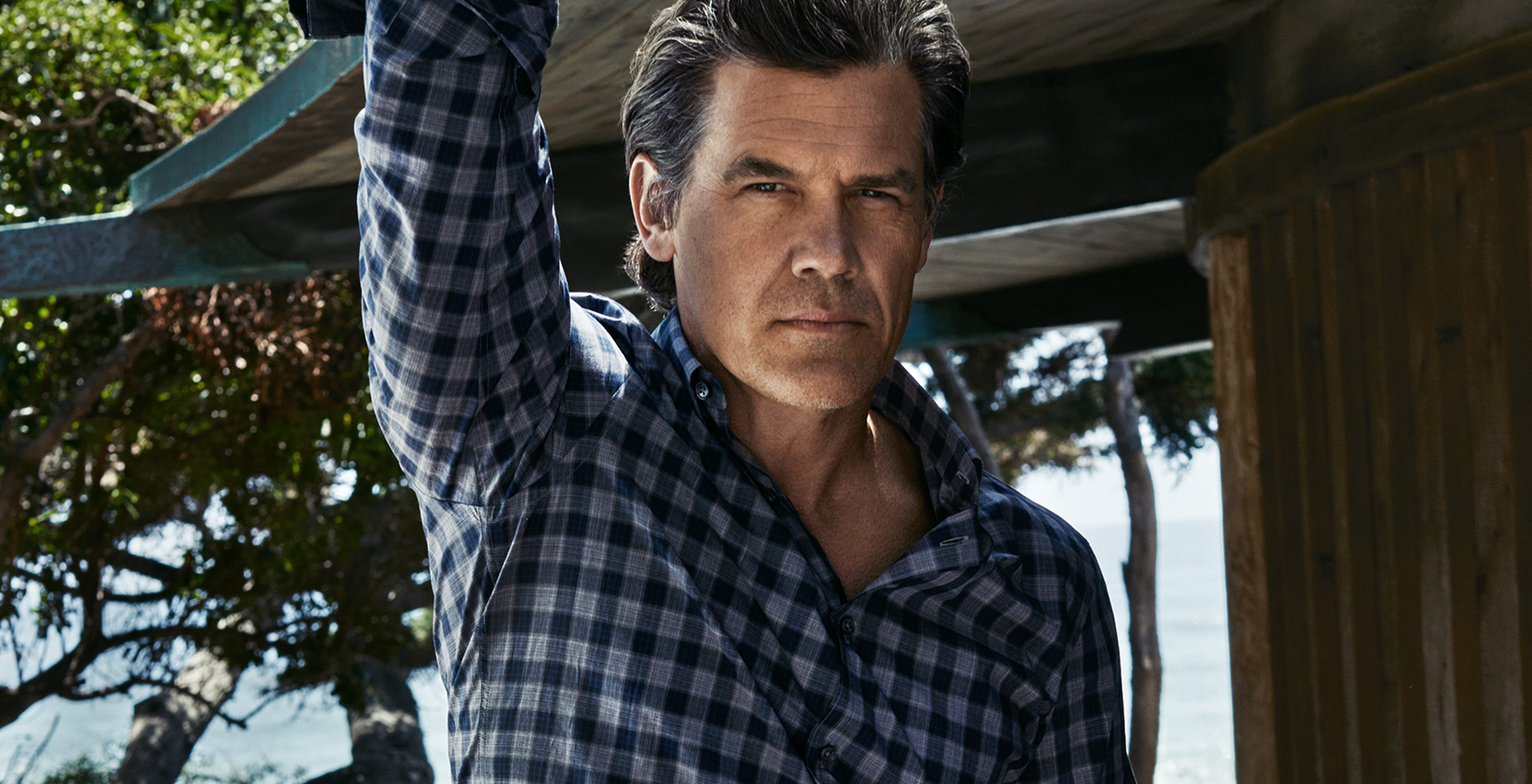

Josh Brolin’s Massive Gains: How the Actor Smashed Through His Comfort Zone to Play Thanos and Cable

Here’s how you grow muscle:

Lift something heavy, like a dumbbell or a tractor tire or a barrel filled with rocks and sand. Feel the blood flow, the swelling, the low-key, radiating pain. Stress the muscle fibres to the point that they damage, shredding like a frayed length of string cheese. Rest. Then do it again, making everything harder. The essence of strength, after all, is discomfort.

Recently shredded and massively swole, Josh Brolin thrives on discomfort. On Instagram, Brolin has been flexing as of late, showing off the substantial gains he’s made getting into shape to play cybernetic mutant bad guy Cable in Deadpool 2. Spending up to two and a half hours daily in the gym, the 50-year-old actor has busted into middle age like a clenched robotic fist punching through the fourth wall, pushing himself well outside his comfort zone. “The more uncomfortable I feel,” says Brolin, “the more confident I am that I made the right decision.”

No pain, no gain.

•••

Brolin’s buffed for a blockbuster spring. In addition to facing off against Ryan Reynolds’s wiseass hyper-violent Marvel Comics mercenary in Deadpool 2, Brolin’s also playing the galaxy-gallivanting baddie Thanos in Marvel’s superhero epic Avengers: Infinity War, already projected to be the most profitable movie of 2018.

Until now, Brolin’s exposure to the modern mega-scale superhero blockbuster had been limited and largely unrewarding. In 2010, he starred in the supernatural cowboy thriller Jonah Hex, based on a relatively obscure D.C. Comics character. The film was a massive flop, and savaged critically. “Nothing turned out,” Brolin remembers, running through the film’s laundry list of failures. “Everything bit me in the ass.” He ended up apologizing to co-stars John Malkovich, Megan Fox, and Michael Fassbender for involving them in the movie.

In 2014, it was reported that Brolin turned down the role of Batman in D.C.’s newly launched Justice League universe, a role that subsequently went to Ben Affleck. Instead, he focused on smaller, meatier character roles, drawing praise for his comic turn as a clean-cut cop in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice and as a maniacal Department of Justice operative in Denis Villeneuve’s drug cartel thriller Sicario (Brolin reprises the role in the forthcoming Sicario sequel, also due this summer). Even his turns as Thanos in Marvel’s shared “Cinematic Universe” were, until Infinity War, mostly cameos.

Then he got his hands on the script for Deadpool 2. “I’ve said no to a couple of bigger movies that were this type of thing,” Brolin explains. “My wife, very smartly and sweetly, pointed out that I was rebelling against being in one of these movies. She said I should just read the script. She was right. I read it and I cracked up.”

The original Deadpool movie was a long-gestating pet project of Canadian Ryan Reynolds, who saw potential in a D-string superhero whose artillery includes winking meta-humour among a cachet of automatic weapons and twin samurai swords. Imagine a cross between Marvel’s heavily strapped Punisher, Zack Morris from Saved By the Bell, and the cartoonishly manic “S-s-s-s-somebody stop me!” shtick of Jim Carrey in The Mask and you get an idea of Deadpool’s hyper-violent comic energy.

For Brolin, the chance to play a time-travelling cybernetic foil, the straight man to Reynolds’s wisecracking stooge, offered a unique challenge. Beyond the drastic body transformation required for the role, keeping up with the on-set riffing of his co-stars (including funnymen T.J. Miller, Terry Crews, and Rob Delaney) was daunting. “Suddenly I’m in the nucleus of this insane stand-up comic fest,” he says. “It’s a different muscle. That first day, the feeling that I had absolutely made the wrong choice meant I had made absolutely the right choice. I had no idea what I was doing, and it was perfect.”

Where Deadpool demanded that Brolin — who had just packed on 40 pounds for a starring role in Jody Hill’s Netflix comedy Legacy of a Whitetail Deer Hunter — shred himself into the best shape of his life, his turn as the Avengers banner bad guy was more of a disappearing act. Thanos is a burly, plum-skinned alien demigod whose physique is more inhumanly muscular, and playing him let Brolin lose himself in modern motion-capture technology. It’s the sort of thing that may seem delimiting to an actor of Brolin’s calibre. But he saw it as just another new muscle to be bent into shape. “I had to let everything go,” he explains, “every concept of what I thought acting was. This was like 1970s, Lower East Side Manhattan, we-don’t-have-any-money black box theatre. And that’s what it was — the most expensive black box theatre production ever made.”

“When I’m learning something, I’m uncomfortable. Obviously, I’ve been in situations where I’m uncomfortable because I know it’s going to be bad. Luckily, I haven’t suffered that kind of discomfort in a while.”

Much to his own surprise, he loved it. While his lips are contractually sealed as far as Infinity War’s plot goes, he does manage to drop some lofty, and encouraging, references in discussing Thanos: The Godfather films, Scarface, Heat, and especially Marlon Brando’s maniacal turn in Apocalypse Now. He started aping Brando’s Colonel Kurtz on set, an impersonation that he says shaded his characterization of Infinity War’s similarly control-freakish antagonist. Where Cable required intense training, dedication, and a sugar-free diet, playing Thanos provided the proverbial cheat day.

Given the complex licensing arrangement of Marvel’s superhero properties (Deadpool belongs to 20th Century Fox, while Disney tends the Avengers cash crop), Brolin’s cross-franchise supervillain double take feels brazenly conspicuous — like a two-timer taking his mistress on a date to his wife’s favourite restaurant. But Brolin views the twin roles with a typical sense of pranksterish humour. “I did Avengers, which is the biggest superhero movie,” he chuckles. “Then I’m in a movie that makes fun of all those movies, and they both come out within a few weeks of each other. I like the idea of it. It makes me feel like I’m doing something. Really, I’m doing nothing.”

•••

In his own estimation, Josh Brolin’s career is defined by this pattern of rebellion. He responds to the ever-amorphous concept of “punk rock” — not so much as a genre of music or even a coherent political ethos but as a mode of constant revolt. Revolt against himself, revolt against the expectations he’s been saddled with, revolt against whatever you’ve got.

But does it even make sense for a guy drawing enormous salaries by starring in two of the year’s biggest popcorn movies to compare himself to a punk rocker? “I consider myself a punk rocker who’s now being paid,” Brolin qualifies. “How’s that?”

In his best roles, Brolin has gravitated toward badasses, antiheroes, and even the odd historical villain. His dramatic breakout came in 2007 as the shrewd Vietnam vet Llewelyn Moss in the Coen brothers’ caper No Country For Old Men. This was quickly followed by a starring role in Oliver Stone’s George W. Bush biopic and a career-best turn as real-life killer Dan White in Gus Van Sant’s Milk, a role Brolin invested with impressive nuance. Then, just as the yoke of Serious Actor was about to close on Brolin, he pivoted, making Jonah Hex, appearing in Men in Black 3, and wading into the Marvel Cinematic Universe. “I’m not interested in a groove,” says Brolin. “I enjoy learning something. When I’m learning something, I’m uncomfortable. Obviously, I’ve been in situations where I’m uncomfortable because I know it’s going to be bad. Luckily, I haven’t suffered that kind of discomfort in a while.”

Describing his career, Brolin sounds less like his commanding characters in Sicario and the Marvel movies and more like the luckless Llewelyn Moss: a guy adrift in the sometimes-fickle eddies of fate. There’s no “groove.” No calling. No master plan. What attracts him is that sense of writhing discomfort, of learning to grow under stress.

Brolin’s drive is tinged by humour (just check his Instagram, where he both diarized and satirized his intense workout routines, deflating the bulging self-seriousness of gym-bro culture). It’s also grounded in a genuine-seeming honesty. He swears he’s never at ease, still nervous and uncomfortable on set. He tells a story about Jack Nicholson, who, despite being an Oscar-winning Hollywood veteran, arrived on the set of A Few Good Men completely high-strung. “That’s me,” says Brolin. “There’s this idea that the more successful you are, the more confidence you have, the more you’ve arrived. There’s something intrinsic in me where I think that’s a death. That’s the death of an actor, the death of skill, the death of what you’ve been building toward.”

Brolin has sculpted a brawny career, straddling leading-man and character-actor status, bouncing between lauded American masterpieces and certified stinkers. It’s a body of work that’s seen him bloating, cutting, shredding, pushing himself, rapidly shifting between different modes of moviemaking like a gym rat looping through a punishing circuit-training routine. When you’re never at ease at work, it only makes sense to pursue the things that make you uneasy. Josh Brolin has made massive gains straining himself like this. His unceasing discomfort, it seems, is his strength.