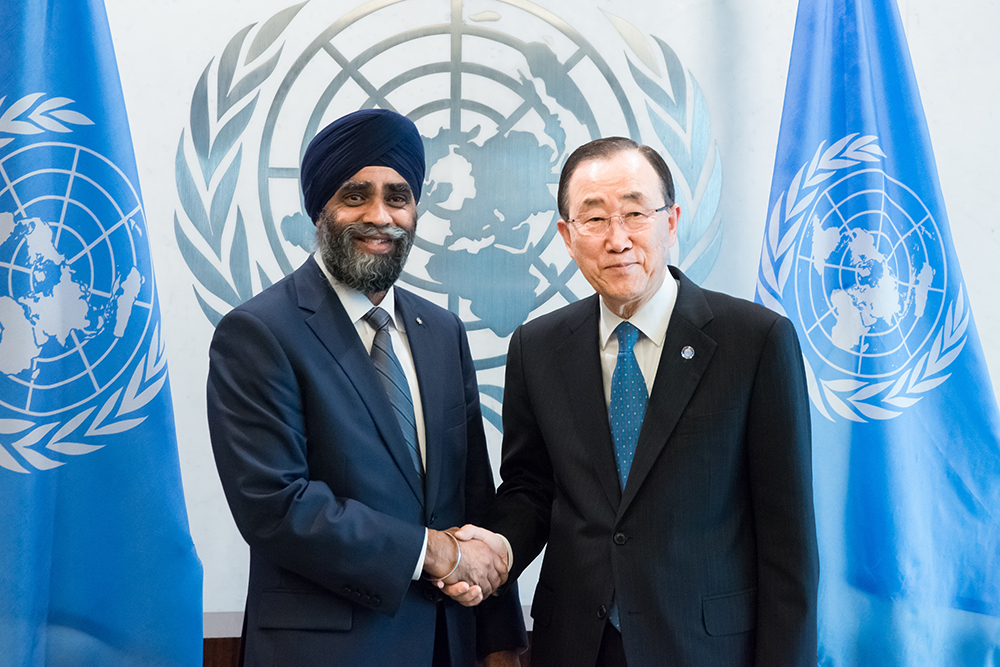

War and Peacekeeping: Canadian Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan Opens Up About His Biggest Challenge Yet

Forget what you’ve heard: Harjit Sajjan is not a badass.

For many Canadians, that’s the first word that comes to mind when talking about the current Minister of National Defence. Sajjan’s reputation tends to precede him: he is one of the country’s most decorated military veterans and a former Vancouver police detective celebrated for breaking up organized crime rings. He holds a patent for a gas mask. He’s a black belt in jiu-jitsu, and he was once featured in a Dick Tracy comic. There’s even a sign behind the desk in his office: “Warning — badass parking only.”

But spend some time with him and you won’t find him striving to live up to any sort of tough-guy identity.

Instead, shuttling between meetings and interviews, he projects a calculated steadiness, derived from his time spent witnessing the exact opposite: chaos, uncertainty, and fear.

In late March, Sajjan announced Canada’s next peacekeeping mission. As many as 250 troops will be sent as part of a helicopter task force to the north African nation of Mali. The country has been a staging area for Islamist militant groups looking to launch attacks in neighbouring countries, and is in the midst of a brutal civil war that has so far drained billions in foreign aid and taken the lives of more than 160 UN peacekeepers.

This was Sajjan’s biggest announcement since taking up the National Defence post in 2015. Canada has struggled to assemble a meaningful peacekeeping force for almost a generation; the March announcement marked the largest contribution since the slow erosion of the country’s peacekeeping presence in the 1990s. Three decades ago, Canada made up 10 per cent of the global peacekeeping force. Today, that figure has plummeted to a mere fraction of a single percentage point. Ethiopia deploys more than 8,000 soldiers to United Nations peacekeeping missions. Canada provides only 68.

Sajjan sees Mali as a chance for Canada to test a new theory of peacekeeping. Canadian soldiers are great at many things and excel particularly at a few, like helicopter combat and search and rescue. So, the new logic goes, why not let nations build their missions around those core skills, sending select troops to the places where they can deliver the biggest impact? That’s exactly the sort of reasoning Sajjan would like to be known for — more tactical than badass.

•••

To understand Sajjan’s view of peacekeeping — and, by extension, defence — it’s helpful to trace the story of his life. Born in a small village in the Punjab region of India, he moved with his family to Vancouver when he was five years old. His father, previously a police constable in India, took work in a sawmill. His mother worked on a berry farm and as a chef.

The early years were difficult, as his family faced poverty and racial discrimination. “I saw some of the negativity of society, and I almost got sucked into that as well,” he says.

At 16, he began to wear a turban, even though his family wasn’t religious. For him, it was a way to connect to a larger story and forge an identity of his own when he wasn’t quite sure where he belonged.

“This identity was created not from a religious sense but so that a Sikh could be singled out,” he says. “You can rely upon them and ask them for help. But also, if they did anything bad, they could be singled out [for that] as well.”

After graduating high school, he joined the British Columbia Regiment, the same unit that in 1914 helped bar hundreds of Sikh immigrants aboard the Komagata Maru from entering Canada.

“If you can demonstrate that you’re serious about who you are, you’re going to have instant rapport and you’re going to get down to business.”

“If somebody tried to prevent me from a goal, I had a rule,” he says. “Pick a goal even higher.” In 2011, when Sajjan was named commander of that regiment, he became the first Sikh in Canadian history to lead a Canadian Army reserve unit. (He’s also the country’s first Sikh Minister of Defence.) Sajjan’s service would eventually extend to four deployments abroad as a reservist — one to Bosnia, and three to Afghanistan.

He showed the same resolve in the world of policing, where he would go on to work more than a decade as a detective focused on organized crime. “When I decided to choose my identity and put a turban on,” he says, “for me it was almost a natural fit, to put the uniform on as well and serve.”

In 1996, he married his wife, Kuljit. Twelve years later, they started a family and now have two small children, Jeevut and Arjun.

Both at war and on the streets of Vancouver, Sajjan excelled at weaving himself into residents’ lives. “It can take multiple meetings to build a rapport,” he says, “but if you can demonstrate that you’re serious about who you are, you’re going to have instant rapport and you’re going to get down to business.”

It was the soft skills that he displayed, noted quickly by his superiors, that elevated him into positions of influence. On deployment in Kandahar, his fluent Punjabi, together with his distinct appearance, helped him develop trust with local leaders. “He’s passionate about what he does,” says retired brigadier-general David Fraser, Sajjan’s former commanding officer in Afghanistan. “He’s got a heart of gold.”

•••

In many ways, Sajjan’s resume reads like it was tailor-made to secure him his current post. Among his 13 honours is the Order of Military Merit, the second-highest order issued by the Governor General. And yet, Sajjan’s critics in Parliament were quick to turn his past credentials against him.

Last year, he faced heavy condemnation after overstating his role in Operation Medusa, a Canadian-led offensive to regain government control in the Kandahar province. At the time, Medusa was the largest NATO-led land battle ever. “On my first deployment to Kandahar in 2006, I was kind of thrown into an unforeseen situation and I became the architect of an operation called Operation Medusa,” he told an audience while in New Delhi.

His “architect” comment was met by heavy criticism by other service members. “What he did was wrong, and now he has lost the confidence of our men and women in uniform,” said interim Conservative leader Rona Ambrose, calling Sajjan’s words “stolen valour.” Then-NDP leader Tom Mulcair called Sajjan’s statement “a whopper,” demanding his resignation.

Sajjan apologized — on social media, to reporters, and in Parliament.

But for the retired lieutenant colonel, the slip-up was deeper than a poor choice of words. It ran counter to the value he places on clear communication, which he has worked to make the very foundation of his career. “If I say something that makes great sense to me but you may interpret it differently, I’ve just made a mistake,” he says. “I want to say something you’re going to interpret in a manner that the interpretation is what I want you to have.”

This cerebral approach didn’t play well on the floor of the House of Commons, but it fits into a much larger and layered world view that has come to inform his time at the helm of the defence ministry.

And it matters, because war itself has changed. Traditional peacekeeping — which Canada first helped lead in 1956 — happens when two countries agree to a ceasefire and request that the international community deploy troops as an impartial third body. Now, clearly defined sides are rare in most conflicts. Instead, battles today are fought along smudged ethnic and sectarian lines. Re- bel and militant groups often fight governments and target civilians, creating messy, protracted swamps that suck in resources, leaving only tragedy, frustration, and confusion.

The model most Canadians know as peacekeeping began to crumble in the early 1990s, reaching its crescendo in Rwanda in 1994. The UN mission there was tasked with maintaining a tenuous peace, yet was staffed with scarcely enough troops. Experts now agree that the mandate provided by the UN Security Council was insufficient to fully address the scope of the problems in the east African nation.

The result was a genocide that the UN mission was powerless to stop, despite every attempt by Canadian General Roméo Dallaire. The failure stained the conscience of the international community — including Canada — and portended the unspooling of global peacekeeping.

In hindsight, the trouble with Rwanda exposed a systemic problem with the peacekeeping ideal: deploying missions in conflict zones without providing the necessary tools and troops needed to intervene and bring the conflict to a halt.

“It’s what happens when you don’t have an effective mandate,” says Sajjan, who was a reservist at the time. “You don’t have effective resources put in place. You don’t have effective rules of engagement. You don’t have other partners helping you.”

Three years after Rwanda, in 1997, Sajjan deployed to Bosnia, the tiny, ruptured corner of Europe undergoing a brutal civil war. This was the mission that hastened Canada’s retreat from traditional peacekeeping once and for all. The UN was, once again, failing. NATO took charge — with the full force of fighter jets — to end the conflict. For a young Sajjan, Bosnia had a lasting impact. “It demonstrated to me that when you have a strong mandate to deliver — especially when you’re in uniform — you can get things done.”

His time in the war-torn country also exposed the importance of being on the ground and meeting people. His turban — once a source of racial aspersions at home — served him well in a country racked by deep sectarian tensions and a wariness of uniformed troops. “Serbians would look at you like, ‘Who are you?’ They don’t know if you’re genuine,” he says. “I remember saying to them ‘Listen, I’m not a Muslim and I’m not a Christian. I’m probably the most neutral person here.’”

It’s those firsthand experiences that Sajjan draws on in Parliament. Canada is no longer in the business of simply offering up troops to fill quotas. But, at the same time, the Trudeau government has announced a recommitment of Canadian soldiers to the peacekeeping cause — deploying as many as 600 over the coming months.

For that, credit Sajjan, who believes that the country can still play a critical role in humanitarian missions without putting large numbers of soldiers on the ground or becoming involved in direct conflict. Instead, Sajjan plans to amplify the country’s presence in conflict zones like Mali by taking a straightforward approach: fewer soldiers, bigger impact. To leverage the extensive training that Canadian troops have had with search-and-rescue helicopters across the country, and with combat helicopters in Afghanistan, most of their time in Mali will be spent in the air.

“You need to analyze the situation you’re going into. You need to analyze it well,” he says. “And once you have a good understanding of what’s happening on the ground, you don’t have to develop a strategy — your strategy is situational awareness.”

Or put another way: know what you’re getting into. And when possible, prevent conflict from spilling over in the first place. Good defence doesn’t come from the gun, he says. “The military buys you time to actually work on the other root causes.”

•••

In the days after his peacekeeping announcement, the minister’s hours are packed with meetings and television appearances. He extends an invitation to the taping of a political news show to make the case — yet again that week — for the mission. At the television station, the program’s host, Evan Solomon, asks him about Sikh nationalism — a line of questioning familiar to Sajjan and other newly prominent Sikh Canadians, including federal NDP leader Jagmeet Singh.

Even as defence minister, Sajjan still gets questioned about his loyalties. These, says Sajjan, are the kinds of discussions that prompted him to get into politics in the first place. “What if somebody says, ‘What if I become a police officer, maybe then someone will consider me as a Canadian?’ ‘What if I join the military? Maybe I can be trustworthy and considered as a Canadian,’” says Sajjan, voice still steady. “Well, hell. I’ve done both. If they see me — that I’ve done both and I’m a minister now — and I still can’t be believed, what does it take for them?”

The organized chaos of Parliament is miles away from his life three years ago. His children visit him in Ottawa, but the distance wears on him. Pictures drawn by them are placed next to gifts from high-ranking military brass around the world. “My daughter told me she hopes I don’t get re-elected,” he says, two years into his first term. A photo of Kuljit and Jeevut seeing him off for his Afghanistan deployment rests beside stacks of documents. But there’s a lot of work still left to do. “If you want to make a difference,” he says, “you have to go where the decisions are made.”

As Mali looms, Sajjan faces his biggest, most complex challenge to date.

He admits his story, from plucky kid trying to find himself to decorated minister of defence, isn’t conventional. But neither is he. And at times, his life has been a hard-won lesson reinforcing that fitting in — and conforming — is the easy route. Not everyone will pat you on the back for going in the other direction. “That’s the reality of it,” he says. “But that’s okay, because it’s just going to drive us even harder.”