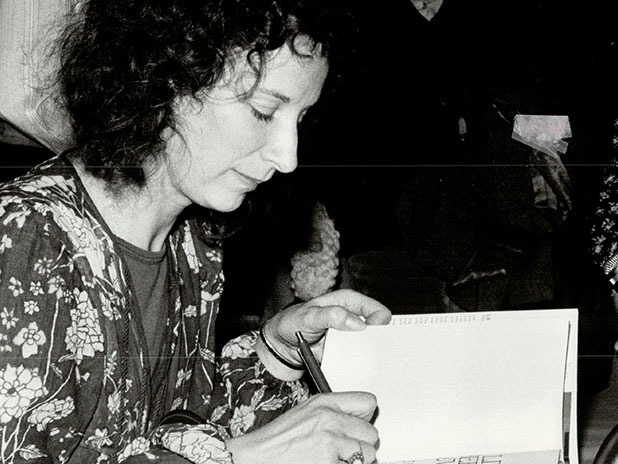

Margaret Atwood Is Ready for the End of the World

If Margaret Atwood has an unofficial motto, it’s “Can’t Stop; Won’t Stop.” Since self-publishing her first book in 1961, she’s released more than 60 award-winning novels, short story collections, children’s books (sure), collections of poetry — and still had time left over to write the odd television script and opera libretto (why not?), appear at a handful of festivals and conferences every year, throw her weight behind a few dozen worthy causes (birds and the environment, especially), and tweet out to her more than 800,000 followers. At 75, an age when a lot of her writing peers have become mired in the nostalgia for a sepia-tinted past, she continues to be obsessed with telling us about the future—specifically, which cliff we’re about to go over next.

That is the one of the arguments for paper books, that at least if all the lights go out you’ll be able to set them on fire.

For decades now — especially in her recently completed MaddAddam sci-fi trilogy, which is currently being turned into an HBO mini-series by director Darren Aronofsky — she’s been creating dystopian visions of humanity’s fate that are as wickedly satirical as they are deadly serious. Her new novel, The Heart Goes Last, depicts a not-too-distant future in which people make ends meet by getting paid to be prisoners in for-profit jails. It’s not a particularly cheerful vision, but you get the sense that Atwood is as amused as she is concerned by the mess that humanity is constantly getting itself into. If we really do go over an apocalyptic cliff one day, it’s hard not to imagine her standing right at the edge, watching us fall, making notes toward a new book or three.

When I was preparing for this, I came across a story about Atwood Oceanics, a deep-sea drilling operation.

They’re probably relatives of mine — there aren’t that many Atwoods on the planet.

I had a brief moment where I thought maybe this was one of your many side projects.

It’s not, but I did have to kick two other “Margaret Atwoods” pretending to be me off of Twitter. I think they were tribute accounts of a strange kind: they were posting things they thought I might conceivably say or do. They weren’t right about that.

Given how engaged you are on Twitter and how often you are quoted in the media, I’m amazed that you’ve mostly avoided being at the centre of a scandal for something you’ve said. It seems to happen to every celebrity at least once.

I think some people are just too quick off the mark. They jump the gun before they’ve really investigated what the fuss is about. You saw that with the Jian Ghomeshi thing.

You mean, people jumping in to defend him when it first came out.

Yes, and you could see why people would. But they quickly jumped out again.

Do you feel sympathy for writers who prefer the old-school method of shutting up between books and staying away from social media?

Absolutely. They’re not cut out for it. They weren’t on the college debating team, they have thin skins and they’re easily wounded, and should stay away from it, no question. What writers should do primarily is write their books. But that doesn’t mean that that’s the only thing they should ever do. That’s the “art for art’s sake” position, which is in itself a moral and philosophical stand. In a way it’s true, but in a way it’s not true, because that’s not what human beings are like — they will put a moral in whether you want them to or not.

The Heart Goes Last began as a serialized story online. Have you reworked that material?

I absolutely had to, because when you’re writing a serial, you have to keep reminding people of what happened the last time. A lot of stories were serialized in magazines and newspapers up until the 1970s. The Internet has taken the place of those spaces. You see these experiments happening now — even Fifty Shades of Grey started as online fanfic.

Unlike, say, Fifty Shades of Grey, the story you came up with is not exactly a beach read.

It’s fairly dark. I realized about three quarters of the way through that I was channeling Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, which is funny from the point of view of people watching it, but it’s not at all funny for those who are actually in it. So I put a quote from the play at the front. I also used a quite hilarious quote that I found online in a blog post called “I Had Sex with Furniture.” He begins by saying, “I did this so you don’t have to.”

Even as you are positing possible future dystopias, you are constantly referring back to classic literature.

Anything we’re doing now we’ve already thought of about 4,000 years ago. Look at desire: the first gorgeous female robot is in The Illiad, where Hephaestus has these golden females he’s created to be his helpers. Pygmalion and Galatea: same story. And there was a big piece in Vanity Fair recently about life-sized sex dolls you can have custom-made to be your pal. It’s nothing new.

The new novel posits a future in which people are willing to trade their freedom for financial security.

People always have been. Having been a World War II baby, I read a lot about Hitler, and that’s what happened, that’s how he got power. He was promising full employment, a chicken in every pot, and fun vacations. Who wouldn’t like that?