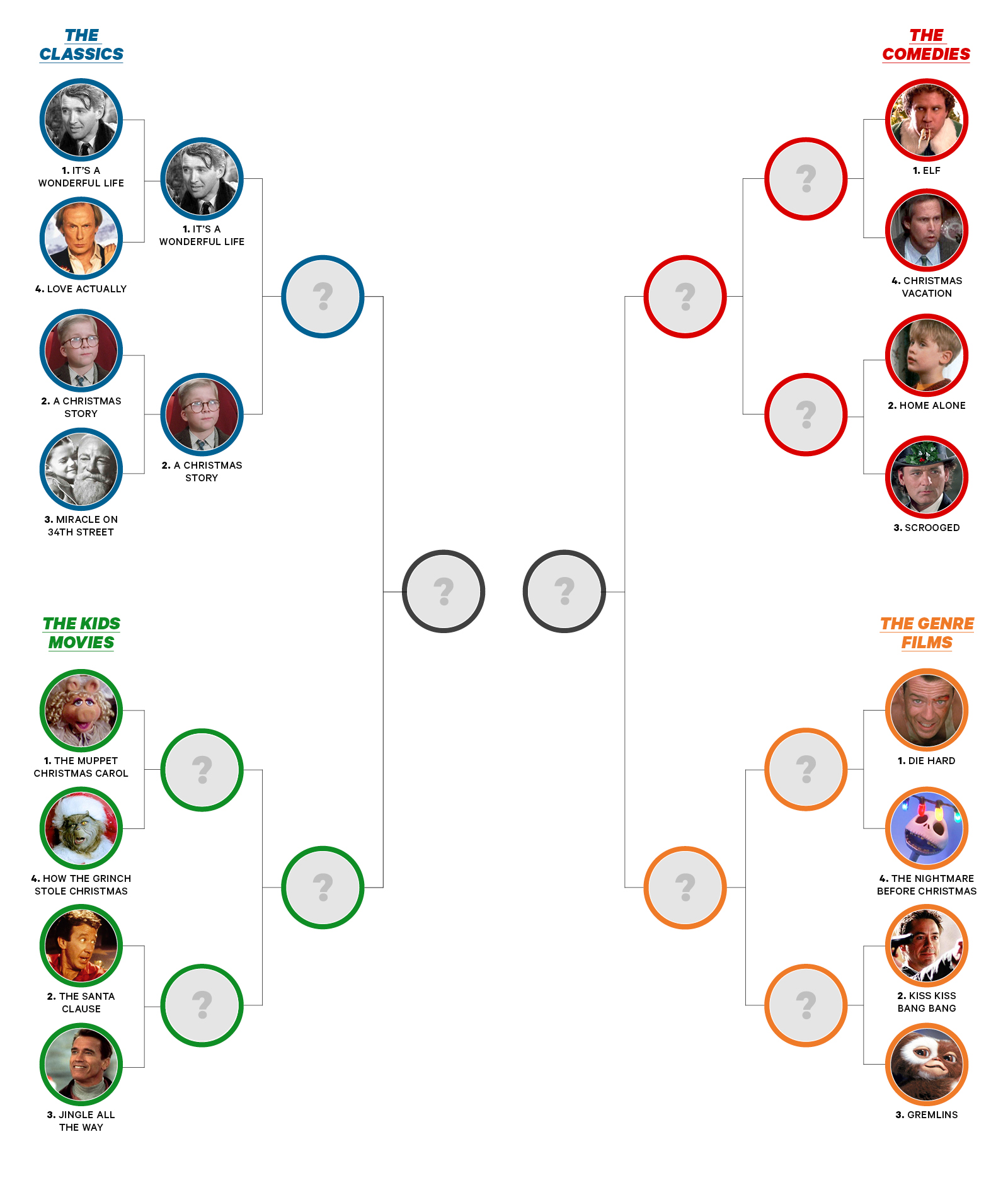

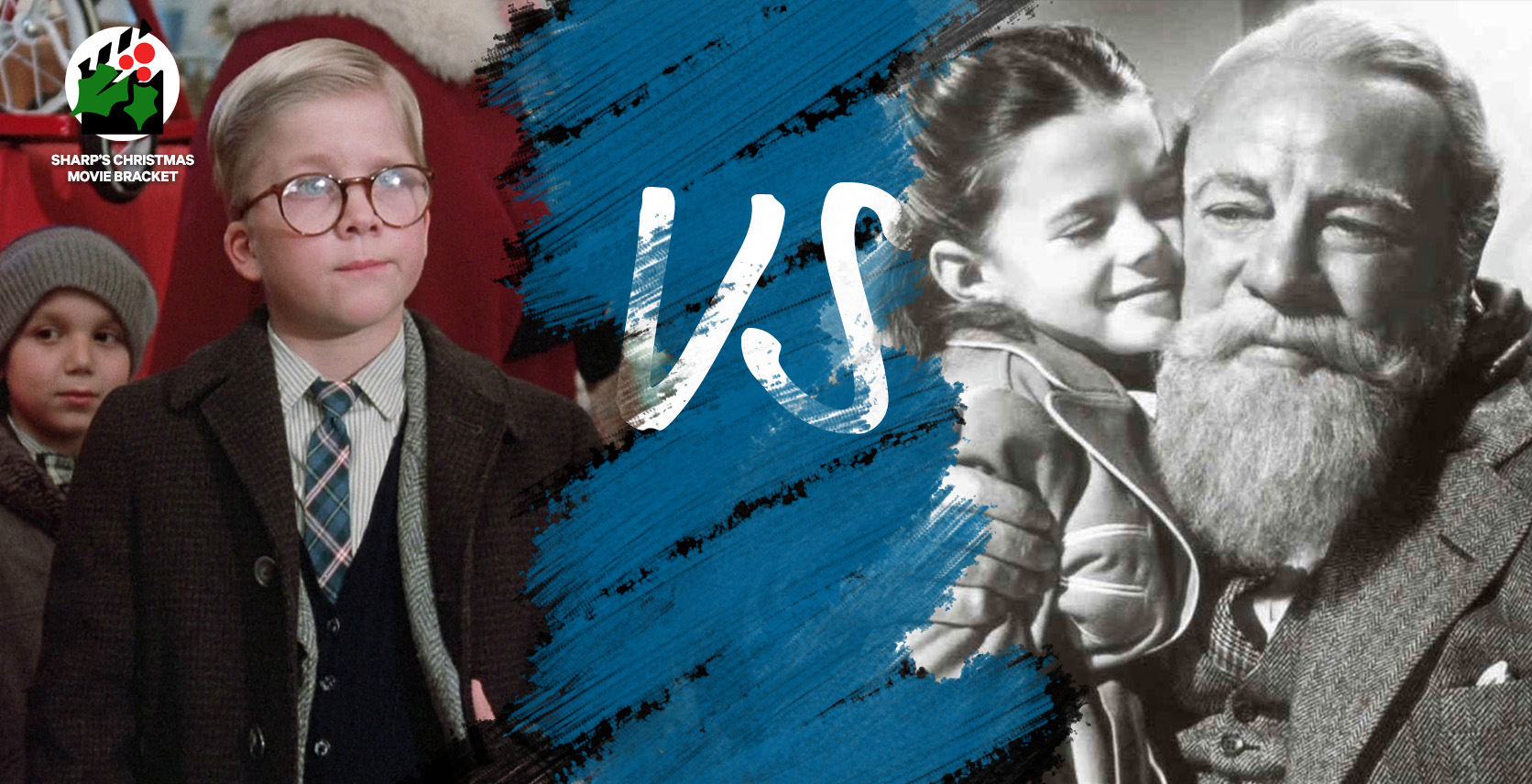

Christmas Movie Smackdown: ‘A Christmas Story’ vs. ‘Miracle on 34th Street’

To read more of Sharp’s Christmas Movie Smackdown, click here.

Yes, we’re aware of Miracle on 34th Street’s vaunted legacy — that it won several Academy Awards back in 1947, that it’s been adapted four times since, and that it continues to inspire heartwarming acts of holiday kindness. It’s more than a Christmas movie; it’s a goddamn Yuletide institution. We’re also well aware that A Christmas Story’s legacy, by contrast, is simply that it’s been played on TV a heck of a lot times. And that people like to watch it.

But that last part is important. People really — really — like watching A Christmas Story. So much that this marks the 19th year TBS will air a day-long marathon of it. Turns out viewers aren’t yet tired of this story about a hapless, bespectacled kid and his desire for a BB gun that he’ll likely shoot his eye out with. When was the last time you saw a Miracle on 34th Street marathon? Exactly. It would never fly; the movie’s so sappy — it can literally be tapped for syrup — that too much of it would cause a continent-wide diabetes crisis (well, even more of one). A Christmas Story, however, is schmaltz-less enough to be endlessly re-watchable; its gags — the awkward bunny suit, the leg lamp, “I can’t put my arms down!” — slay every time. Not bad for a flick that fared poorly during its opening weekend back in 1984.

Ironically, the very thing that kept it from being a box office behemoth is actually what makes it so easy to digest over and over again: A Christmas Story doesn’t have much of a plot. Its only constant is Ralphie Parker’s relentless pining for the aforementioned BB gun. (More specifically, a “Red Ryder BB gun with a compass in the stock and this thing which tells time.”) But the movie itself is really just an eclectic collection of vignettes, which themselves are often plotless, serving mostly as slice-of-life observations about Christmastime and childhood, as told by an adult raconteur. It’s an ideal format for infinite, mid-food coma TV repetition — not just because its nostalgic voiceover technique has had a big influence on single-camera shows (see: The Wonder Years; How I Met Your Mother), but also because you can tune in at its beginning, middle or end and not feel lost at all. Every scene tells its own story, while always looping back to poor Ralphie peering longingly into that store window. And who hasn’t been that kid?

Here, ultimately, is the reason more channel surfers would rather stop on A Christmas Story than Miracle on 34th Street: it’s relatable to pretty well everybody. Sure, Miracle might address kids as real, intelligent people; Susan is one of the smartest characters in the movie, and Santa’s harshest critic. But A Christmas Story speaks better to the universal nine-year-old’s condition. It doesn’t oversentimalize childhood, opting instead for a convincingly specific look at North American family life and the perceived injustices of preadolescence, especially around the holidays. Not many people know what it’s like to meet the real St. Nick (and subsequently support him in court), but we all know what it’s like to have wish list-related anxiety while dealing with snot-nosed bullies, triple dog dares and disapproving adults. Even as grownups, we know the feeling of incessant striving — to reach for something again and again, no matter how many times we get kicked down life’s giant slide with the proverbial boot to the forehead. And we all recognize that the end goal is totally worth it, even if it leaves us lying in bed with our eye shot out.

THE WINNER: A Christmas Story