Billion Dollar Baby: The Scion of the Lululemon Empire Is Setting out on His Own

Tea lights line the cement stairs that lead down to the basement. Behind a veil of black curtains is a room packed with stationary bikes. Pipes protrude from the ceiling, candles cast an eerie glow on the cement walls. If vampires exercised, this is where they’d do it. Moments before, the locker room of Ride Cycle Club’s Underground location on Ossington Avenue in Toronto was filled with bouncy ponytails and cut biceps on body types large and small. When the (mostly Lululemon-outfitted) participants are ushered behind the curtain, the instructor cues up a Skrillex track. Instantly the class is transformed — these people are teeming with energy I would normally only ascribe to a pack of feral cheetahs.

“You’re fucking killing it,” the instructor shouts over a Calvin Harris remix, music thudding so loud there’s a box of neon orange earplugs on offer at the door in case you don’t want your brain rattled. Cyclists spring up and down on their bikes, pumping out mini-pushups in scary synchronicity. The instructor, Jessie, shouts out a militant “one, two, one, two” through the entire 50 minutes, with enthusiasm that only seems to build throughout the class until she’s before the first row of bikes, shaking her butt to Dr. Dre and encouraging riders to “lean that ass back” and stay up out of the saddle.

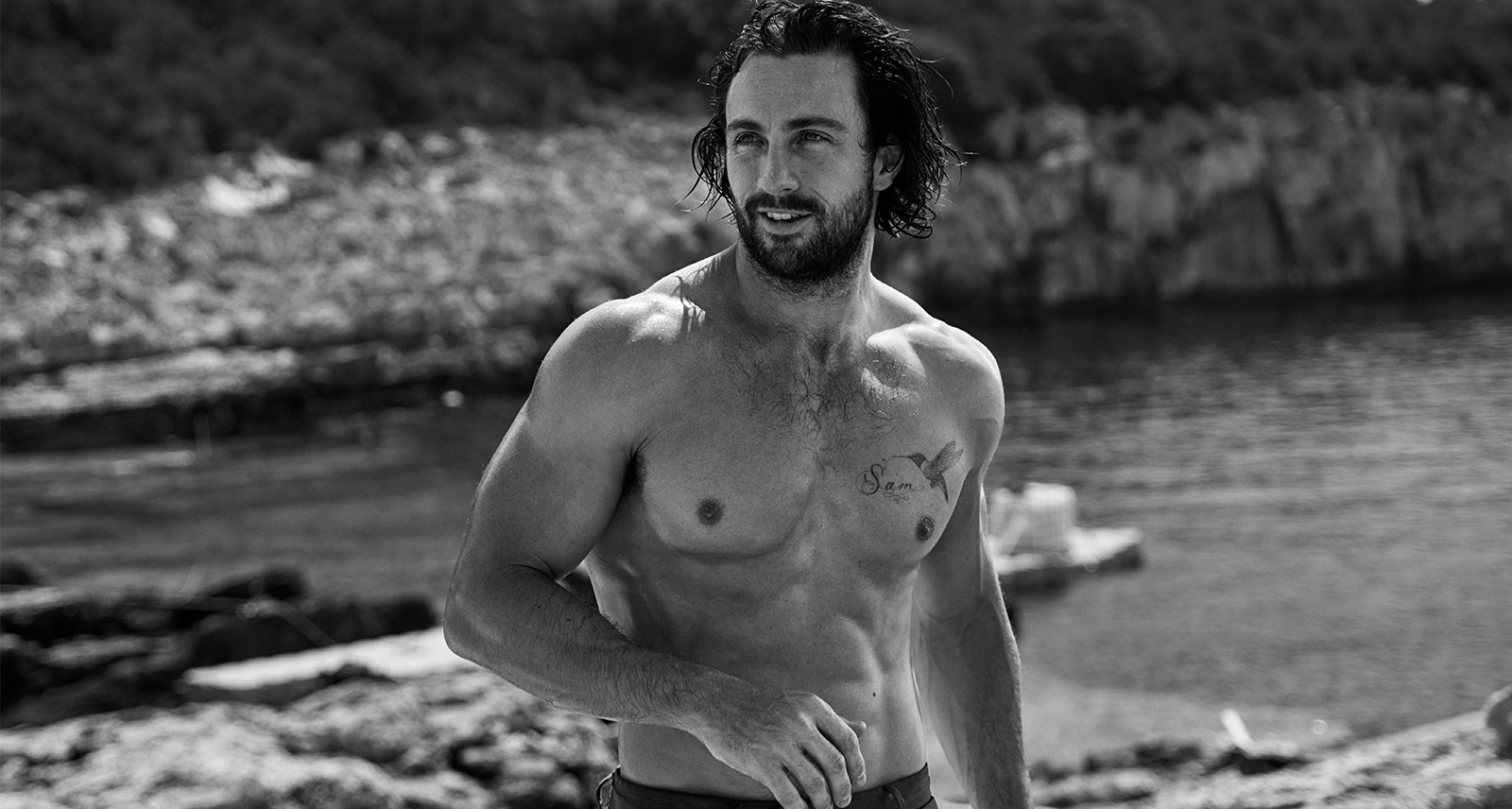

Ride Cycle Club, an indoor cycling studio that started in Vancouver’s Gastown neighbourhood, is the newest incarnation of the boutique fitness trend in North America. The mood is a little bit like SoulCycle, the upscale New York studio that just opened a Toronto location, minus the cheesy mantras those instructors toss out during classes. Instead, it incorporates some of the industrial aesthetic and aggressive don’t-quit attitude of CrossFit to make a type of class that appeals less to the investment bankers and club kids of King Street West and more to the health-goth (yes, it’s a thing) hipsters of Ossington and Gastown. The business is the brainchild of JJ Wilson, co-founder of clothing chain Kit and Ace and son of Lululemon founder Chip Wilson. Like his father, JJ — short for John James — is a compelling advocate for a life intensely focused on exercise. He’s charming, handsome, and totally addicted to the grind. And, as the 28-year-old prepares to expand Ride Cycle Club from one studio in Vancouver to six across the country, he’s moving away from the family business to see if he has the makings of a retail tycoon himself.

•••

When JJ Wilson was 10, he rounded up the kids in his Vancouver neighbourhood of Kitsilano and gathered them in his dad’s garage to brainstorm moneymaking ventures. Under his direction, they’d knock on people’s doors hawking their car-wash services or lemonade stands for loonies and toonies. JJ would take 10 or 15 per cent off everyone’s cut, depending on the day.

It was the first sign that the Wilson business acumen might be genetic. JJ had been raised in the Lululemon empire, the eldest son in an athleisure dynasty. An infant with divorced parents, Wilson split his time between his mom, an educational psychologist, during the week, and his dad on weekends. That meant hanging out at Westbeach, Chip Wilson’s surf shop that he later rebranded as a snow- and skateboard shop and sold for $15-million in 1997. The next year, Chip launched Lululemon.

“I’d finish elementary school and high school and Chip would be unable to pick me up because he’d be at the store,” JJ says. He has joked that Lululemon was his third parent. “I’d walk from school to the store and we’d be there until it closed at six or seven.”

The boys would head home for dinner, and during dinner Chip would talk about the business — products that were selling, that weren’t selling, prospective locations, prospective areas for growth. He’d ask his sons for their opinions, even if he wouldn’t take their advice. In Grade 9, Chip pulled JJ out of school for three weeks to take him on Lululemon’s IPO tour. The business and the family were twined together. If the family was vacationing in California, they’d do a real estate tour of LA. In New York, they’d do a retail tour of the top five streets and would go to factories to do sample shopping. “I wouldn’t know any other way of growing up,” he says.

•••

It would be easy for JJ Wilson to be kind of a jerk. His father is worth $3.1-billion. When I ask what he and his friends do for fun, the answer, basically, is travel to exotic locales. His Instagram feed is illustrative: in it, he and his modelesque girlfriend Margot, who works in PR in Vancouver, and their friends and family bask in a slew of tropical destinations (Australia, Palm Springs, the Amalfi Coast). He mugs for the camera in basic-but-expensive athleisure looks. He and his kid brothers vacation in Bali. His siblings walk in a line behind their step- mom Shannon to a jet, a shot hashtagged “growing up wilson.”

When we meet, one sunny day in a divey bar in Toronto, he’s dressed casually in an army green jacket and striped black-and-white T-shirt with close- cropped brown hair, and the first thing you notice about him is his bright blue eyes. The second thing is his broad, earnest smile and the third is his curiosity. Before telling me why Ride is designed the way it is, he asks me what I think. He offers me a solid, enthusiastic high-five across the table when I say I enjoyed it. This is a guy who seems to genuinely care about other people having fun, and keeping healthy. Ride is the natural meeting of those interests.

“When people are first thrown into a group exercise class of that intensity it can be a little overwhelming,” he says in a leisurely West Coast drag. “But I think what we really created is a community of fitness sweat health-goth enthusiasts that use Ride as a social aspect of their lives, which is so important.” Sure, he’s not saving the world. But he’s encouraging people to keep moving and, in his words, “I could have done nothing.”

•••

Wilsons aren’t built to do nothing. It’s not in their blood. JJ was raised by a man whose explicit life plans include both bringing education to all of Ethiopia by 2030 and having 25 grandchildren by 2040. The family has always been about the business — or is it the other way around? Of his kids, Chip has said, “each is a corporation of its own.”

Once a year, Chip gathers Shannon and his five boys ranging in ages from 28 to 10 around the table to set their annual goals. First, they break them down all together — the family’s vision, mission, and goals for the year. Those get posted onto the wall at home and at the family’s offices. Then, each member comes up with his or her own individual objectives, divided into three categories: career, health, and personal goals. For the family, it means monthly dinners together and sales targets for Kit and Ace. For JJ, that means four Ride studios by the end of the year, one Costa Rica meditation retreat, and two rooms in his Kitsilano home furnished, among others. So while he might not be in business with his parents anymore, he’s been groomed by his father and speaks dreamily of one day sharing a business with his wife. “Does Margot know that’s the plan?” I ask. “We’ve talked about it,” he says.

A few times a year, JJ says, his father will bring the goal sheets back to the table and hold his children accountable. “‘Now, where are we at with our goals?’ he’ll ask,” JJ says. No one is chastised, per se, for not making them. But consider the family vision: “We’re a multi-generational family with clear communication and everyone lives fully self-expressed lives.” This is a dynasty in the making, and its heir apparent has bought in. “It’s the best thing to go back and look at my goal sheets. Five years ago, I had a goal that I would be a spin instructor,” JJ says. “You go back and you read them, and you think, What? I didn’t even have a goal that I would own a spin studio.”

•••

Chip is a complicated guy, at best. A former Ironman competitor, even at 61 he has a hulking, muscular physique, a face slightly reminiscent of a sleepy bulldog, and those classic Wilson baby blues. He’s been the source of both sparks of genius (the black yoga pants worn ’round the world) and migraine-inducing scandals for Lululemon, a company he is no longer involved with due to a spate of clumsy PR moves that sent the company’s market share plummeting. Of himself, he has said: “I have my own ideas, my own drive, and I never really agree with other people.” He has a reputation as a hothead, and refuses to hire anyone who won’t undergo the Landmark leadership course, a program that’s been criticized for being cultish. (Landmark has sued people who call it that, but one journalist puts it neatly, saying it’s “simple common sense delivered in an environment of startling intensity.”) He’s made all his kids do it. It’s the reason, JJ says, he can still work with his father — in part, it teaches you how to have difficult conversations.

When Chip took Lululemon public in 2007, the disagreements between him, his various CEOs, and the board escalated to the point where he was asked to resign from his position as chief innovation and branding officer in 2012. But a year later, the Lululemon board asked him to come back to help the company weather a scan- dal that saw masses of customers com- plain that the Lulu pants they’d bought were see-through. Never the diplomat, Chip agreed, stating that the company without him “had lost its way.” Instead of helping, Chip, in an interview, suggested that the problem wasn’t the pants but the size of the women’s thighs. He was demonized in the press for the comments, for which he later apologized, and the company lost $6-billion in market share. The board asked him and Shannon to leave, and he resigned as chairman. He’d later resign from the board entirely.

For his part, JJ took his own sabbatical from the family business early on. After graduating from Ryerson University’s business program, and working part-time as a trend forecaster for Holt Renfrew, Wilson moved to New York to work for the Clinton Foundation and later as an analyst at private equity firm Advent International. When he was offered a job at men’s brand Wings and Horns, running sales and marketing, he jumped at the chance to move back to Vancouver. And, two years later, Lululemon called, asking if he’d come back to the family business and take on a position called men’s vision. After the see-through pants scandal, JJ was swept up in the call for all Wilsons to be eradicated from the company, and left along with his father and stepmother.

Two weeks later, JJ and Shannon decided to start Kit and Ace, an apparel line that sells athletic gear you could wear all day, made mostly from a type of washable cashmere that Shannon developed while she and Chip were on Lululemon hiatus in Australia. At the time, the family said Kit and Ace’s fabric would change the way people dressed and lived the world over. But it hasn’t turned out that way. The Wilsons spent three years expanding Kit and Ace at a breakneck pace, opening around 60 stores worldwide, which some analysts say was a mistake. They’ve since had to close some locations. The clothing is expensive and, according to some marketing experts, not remarkable enough to secure a devoted customer base.

Though Chip has no official role — JJ describes him as a “mentor and adviser” — he is financially invested, and the family has been vague about his relationship with Kit and Ace. One has to wonder whether the notoriously vocal retail dynamo is repeating what happened at Lululemon when he was asked to take a more distanced role — i.e., he couldn’t do it.

Last year, family infighting at Kit and Ace about everything from branding to vision to product lead to Chip deciding that all three family members should step back, especially JJ. He was ousted as chief brand officer, with Chip and Shannon saying in a press release that they were reorganizing their head office staff and effectively removing their son from his position. (JJ remains a member of the company’s board.) In September 2016, the company also laid off 20 per cent of its head-office staff, on top of an earlier layoff of 10 per cent of the team. “The growing pains we’re going through are the equivalent of what a small business might go through at one or two stores. We’re just doing it with 50 and in inter- national markets,” JJ says. Still, he insists there’s no rift and that the Wilson trife ta decided together that the shift was the best thing for the company. “We own and operate it as a family,” he says.

•••

The same day Wilson signed the contract to start Kit and Ace, he also bought a house in Kits Point — a 10-minute bike ride away from Chip and Shannon’s Point Grey mansion, the most expensive in Vancouver at $75.8-million — and signed a formal business agreement to partner with friend Ashley Ander and start Ride.

It started as a passion project, a side-hustle that began when he met his future business partner Ander at a spin class in New York City. Wilson and Ander both moved back to Vancouver, bought six bikes, and began teaching instructors in Ander’s fifth-floor walk-up apartment. Later, Wilson and co. moved into a temporary space, in the basement of a family-owned building.

“One day, I showed up at 5 a.m. and there were 35 people waiting outside. I went, holy shit, other people want this. This is going to be great,” Wilson says. Ride Cycle Club is set to open in North Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, and a second Toronto location by the end of 2017. “Spin is like a drug, right?” Sort of. But the people who like it like it a lot: Ride sells black hoodies with the simple slogan “church.” The studio shares some of its territory with SoulCycle, but Wilson’s not concerned. “I think that how we light the classes allow people to relax and get a little out of their heads. It’s an emotional journey, in a way,” he says. “It’s just the way I want to spin.” His vernacular resembles that of his father describing Lululemon as embracing a lifestyle, and he’s so far been successful at attracting millennial fitness freaks to his studios. There’s something weirdly religious about these businesses, but if they’re helping keep people healthy, that doesn’t seem like such a bad thing. “It’s my meditation, it’s my church, it’s my sweat time. I get lost for an hour, and then I finish my workout and I feel so great,” he says. “The more people I can provide that to, the better.”

Wilson himself works out twice a day most days, hitting a class at Ride at 6 a.m. and doing CrossFit or strength training in the evening before calling his workday quits around 10 p.m. “I hit this stage in my man-life where I just want to push heavy shit,” he says, with a smile and a shrug. In between, he spends mornings at the Ride office and afternoons working at the family headquarters of Hold It All, Inc., the Wilsons’ company for their retail, real estate, equity, and philanthropy portfolios, where he’s developing two other retail projects, though he declines to offer more specifics. Sometimes, Wilson admits, he can get a little fanatical about his work ethic. One weekend in February, he flew his Toronto Ride instructors out to Vancouver. “I made them do three classes a day,” he says cheerfully. “I felt a little bad. By the end, a couple of them started crying.”

But this intensity makes sense, if you consider where he comes from and what he’s trying to do. It doesn’t sound like it, but growing up the son of a strong-minded billionaire has its draw- backs. “How do I feel like I get treated sometimes?” JJ wonders aloud, before a long pause. He tightens his lips into a grimace, the only time during our conversation that he’s not smiling. “Like I didn’t grind it out hard enough. Like I didn’t put in the hard work.”