At the Vancouver Art Gallery, ‘Cabin Fever’ Captures What True, Instagram-less Peace Feels Like

Somewhere north of Yellowknife, deep in the Northwest Territories, a brown plywood cabin with a green door high on a hill keeps watch over a small lake. Even if you had the cabin’s location marked on a map, the pilgrimage required to reach it isn’t exactly intuitive. In winter, it takes a three-hour trip across a frozen Great Slave Lake on the back of a sled, and in summer, an aluminum boat ride followed by a machete bushwhack through the taiga to another, smaller boat stored in the brush along the shore of a second lake. Drag out the boat, pile in, and don’t forget your compass.

When I finally made it there six years ago, two wrong turns on an unmarked trail and a couple of bear scares later, I stepped out of the boat and onto a slice of land that no more than a handful of humans had touched. Maybe it was the deep satisfaction that came from reaching the end of a trying physical journey, or maybe it was watching the service bars on my phone screen disappear one by one until I realized I was entirely out of reach, but trundling across the porch and into that one-room house was to know — if just for a moment — what true peace feels like.

Photo by Greg Richardson, courtesy of MacKay Lyons Sweetapple Architects Limited.

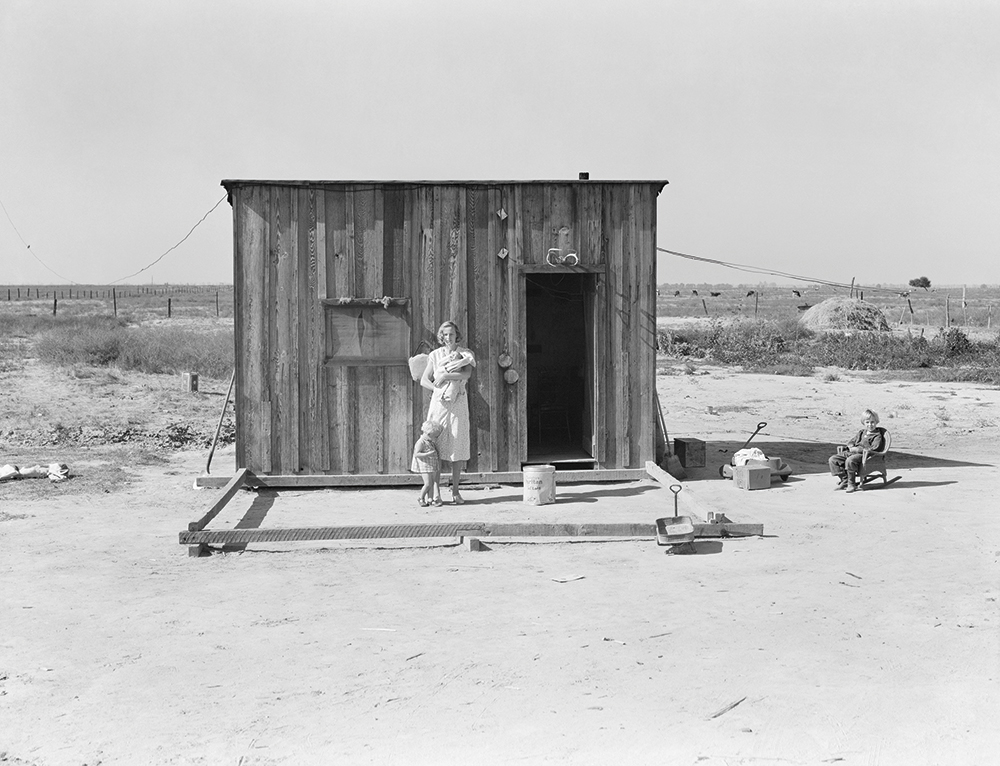

Those who can’t make the trip can come close to grasping a bit of that same tranquility by wandering through the Vancouver Art Gallery’s exhibition. The show, running through September 30, winds us through the structure’s history, and is neatly packaged into three sections: cabin as structure, utopia, and porn. It displays a cross-section of eras and designs, with an undeniable through-line obvious in the examples presented, which range from a 1938 wooden shanty in the California desert to a single-smokestack ice-fishing hut on Alberta’s frozen Ghost Lake.

Evidently, there is something otherworldly and fulfilling, on a primal level, about solitude and isolation — irrespective of income bracket. Gazing at the luxe modernist design of MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects’ Cliff House, a steel box perched precariously over a stunning stretch of Nova Scotia coastline, it’s easy to imagine that those far reaches must surely hold the world’s saltiest air and most refreshing breeze, for those adventurous enough to build there.

Dorothea Lange photo from the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The most iconic cabin in the show is a replica of Henry David Thoreau’s famed retreat on Walden Pond. The writer’s ensuing book, Walden, has become a manifesto of sorts for cabin-seekers hoping to follow in Thoreau’s footsteps and “front only the essential facts of life.” Like the philosopher, who sought to learn whether life in its deepest form skewed closer to cruelty or to the sublime, the show also does some exploring of its own.

After all, cabins have not always been idylls for escape artists. And Cabin Fever doesn’t shy away from the darker and more shameful facets of the cabin’s history — a tool used to colonize and displace Indigenous cultures, and more recently, a visual employed to boost the Instagram followings of neo-Luddites who head into the wild to post pine-tree emojis below perfectly balanced iPhone shots.

Cabin by University of Colorado Denver, photo by Jesse Kuroiwa.

As our expanses get less and less expansive, seeking out the wild and finding a place of true solitude gets more and more expensive. Want to stay in a glass cabin on the far reaches of a fjord in northern Iceland, watching the aurora borealis from your fluffy kingsized bed? That’ll cost $630 a night in the off-season, not to mention the cost required just to get to it. We live in a time when paying to have life’s luxuries stripped away is itself a form of indulgence.

Ken Isaacs Microhouse photo courtesy of Sara Isaacs.

But the thrill of the escape remains undeniable, and my formative Northwest Territories cabin experience sparked in me an insatiable yearning to return to cabin life as often as I can. This summer, I lived in a cottage on Salt Spring Island, B.C., lying in bed every night stargazing through a thoughtfully placed skylight overhead. I spent two weeks alone, eating goat cheese and raspberries, watching deer teeter by the cabin doors on legs like stilts. For days, I waited for the chill of loneliness to set in. It never did.

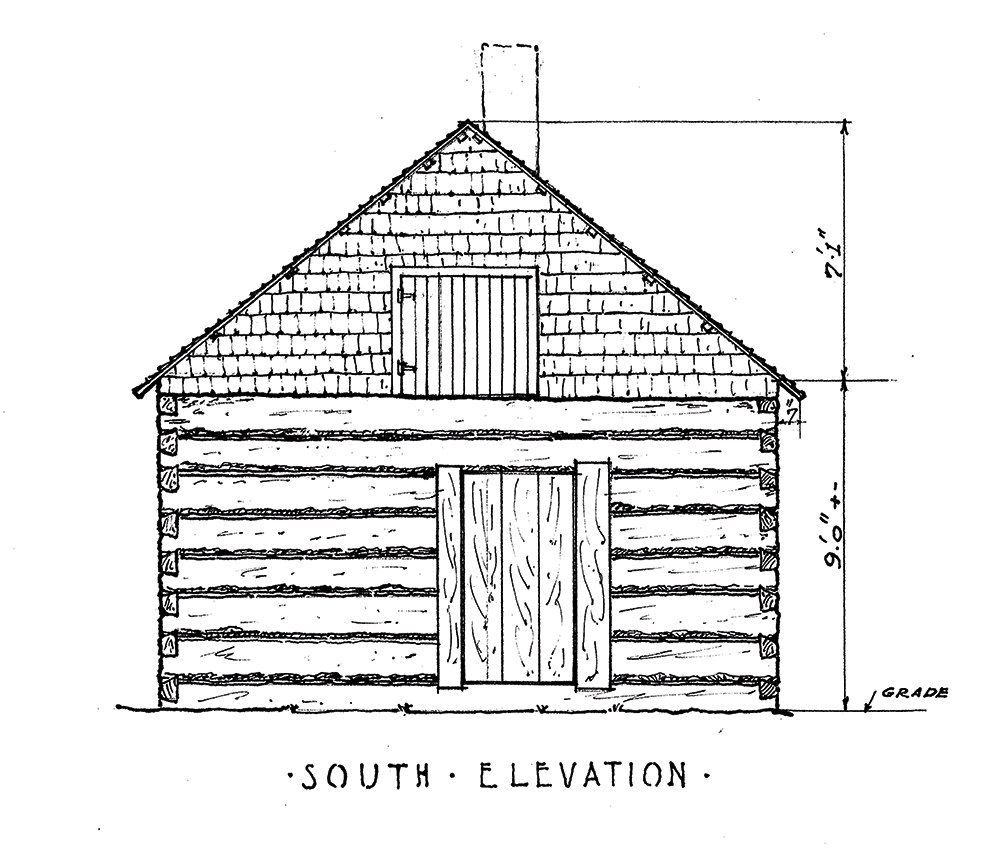

Elevation drawing from the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The more I thought about why I long for cabin life, the more I realized that I’m a student of paying attention — to my friends and lovers, to characters in stories, to strangers who pass on city streets. The muscles required to watch carefully, to take note, and to keenly observe need as much rest as any. After time away, I’m better prepared to take up the field study of humans again. There’s something deliciously recalibrating about it. Even silence sounds like something if you sit with it for long enough.

Of course, the best part of running away is knowing that you have someplace wild, safe, and beautiful to go to. And, as with any retreat, the most fulfilling part is coming home again, to look at life anew.