How Do We Come to Terms with Leonard Cohen’s Legacy in the #Metoo Era?

About a year ago, a friend who, like me, is a huge Leonard Cohen fan, confessed that she’d had a terrible thought: “Thank God Leonard Cohen is dead.” I told her I’d often had the same sentiment. To understand why a Cohen devotee would harbour such feelings, you have to appreciate just how important Cohen is to the people who revere him and how defensive we can get about his legacy.

His life — which began in 1934 and ended on the eve of the 2016 U.S. election — was a tribute to the human capacity for self-invention. In his twenties, Cohen was a poet and experimental novelist. A decade later, he was one of the world’s most distinctive singer-songwriters, having recorded a suite of minimalist folk records with gnomic lyrics. By middle age, he had pioneered a new genre of synth-heavy spiritual pop — liturgical music for secular people who still wanted to infuse their lives with a sense of the divine.

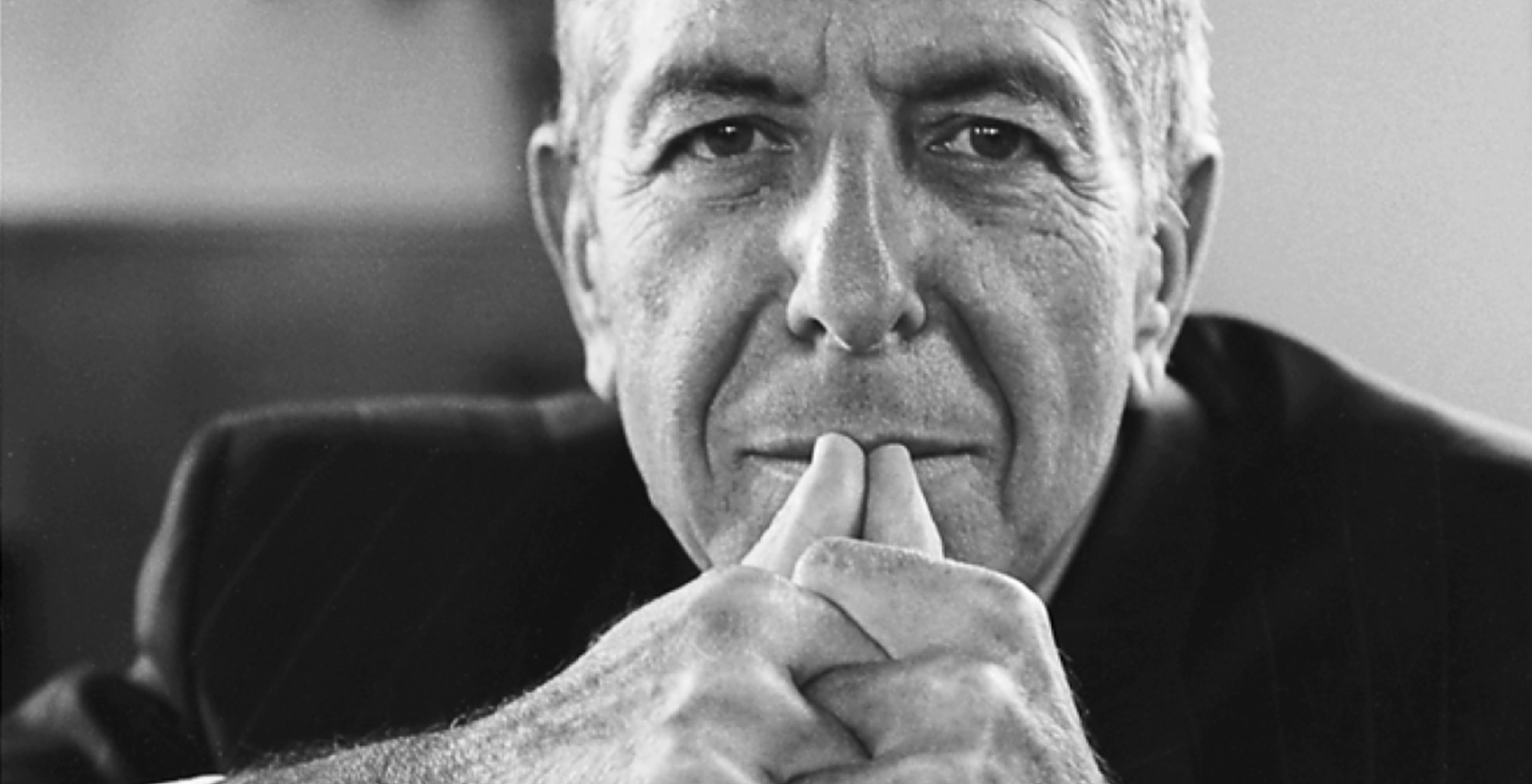

Posthumously, Cohen has been reinvented again. Today, as the second anniversary of his death nears, he has become to his native Montreal what Elvis Presley is to Memphis and Eva Perón is to Buenos Aires: a demigod or patron saint. “Based on how Montrealers are now venerating Leonard Cohen,” Robert Sarner argues in the Times of Israel, “it may be only a matter of time before Saint Leonard appears on local city maps.” His handsome, recognizably Semitic face already graces postcards, billboards, and murals. It is as iconic as the crucifix atop the mountain in the centre of town.

The campaign to canonize Cohen hasn’t stopped there. A memorial concert on the first anniversary of his death featured heartfelt performances from Elvis Costello, Sting, and Lana del Rey. Penguin Random House recently published a collection of his poems, some of them outtakes from his notebook. The dance company Ballet Jazz Montreal has been touring a production set to Cohen’s music. And, following an extended run at the Contemporary Art Museum of Montreal, the show “Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything” will be hitting the road, perhaps until 2022. Cohen is dead, but the Cohen moment is just beginning. He may be more beloved today than he’s ever been.

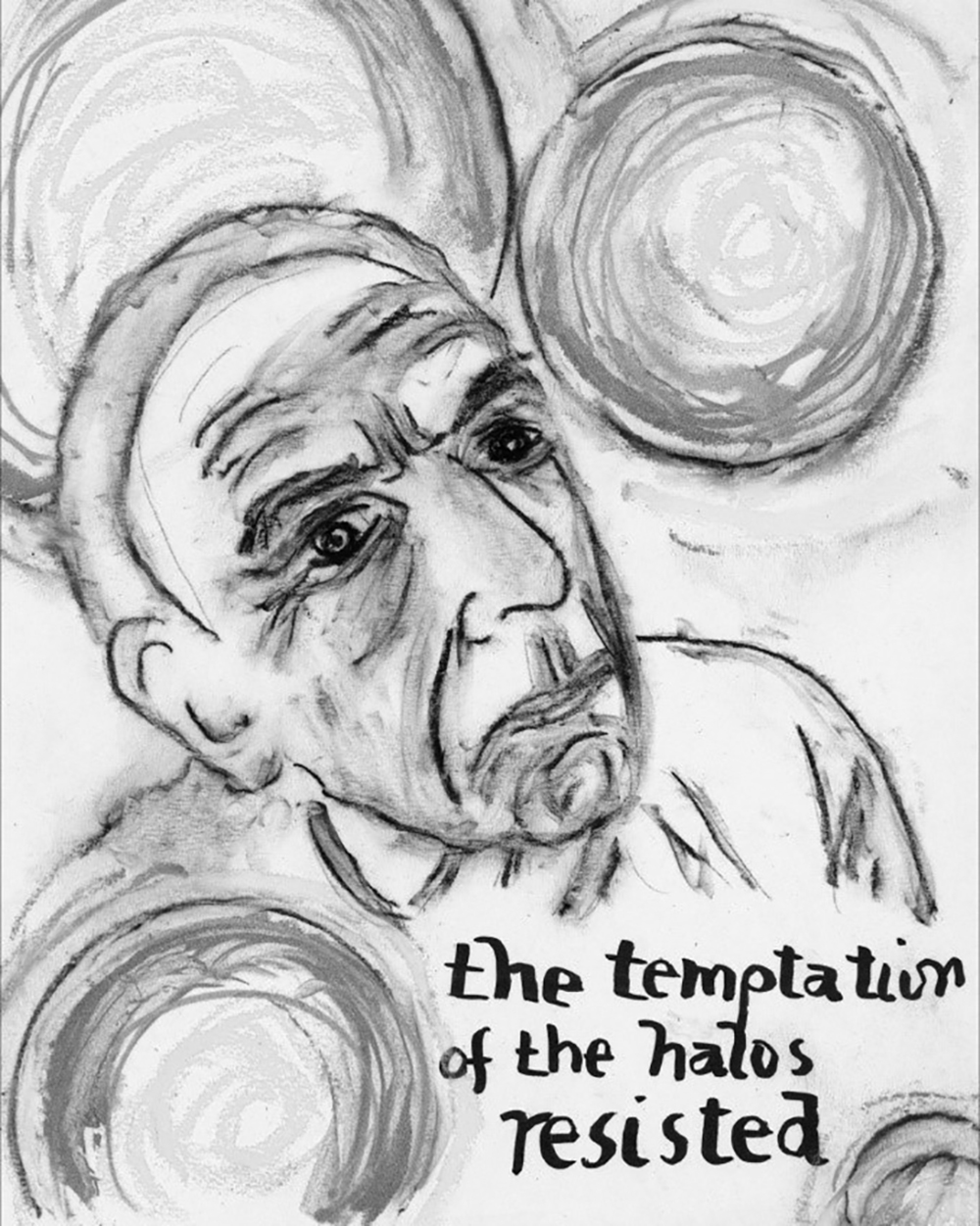

I caught the gallery show in 2017 and was impressed by the variety of work, particularly Candice Breitz’s video installation in which an 18-person choir joyously belts out a full Cohen album, and Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s sculpture “The Poetry Machine,” a vintage organ on which each key plays a spoken line of Cohen’s poetry. The exhibition captures its namesake’s many identities: Cohen the Jew, Buddhist, depressive, guru, balladeer, pop star, classicist, painter, and poet. If there’s one persona that perhaps got insufficient attention, it’s the one you might charitably call Cohen the Libertine — or, if you’re feeling less charitable, Cohen the Misogynist.

Is this a harsh charge? Perhaps, although there was a time when it was frequently levelled at Cohen. The main criticism is that, in his writing, he treated women as set pieces: young ingenues or tragic seductresses. His many love affairs were the stuff of legend. So too were his failed relationships. For fans, his romantic and sexual exploits were a source of fascination, but for those who didn’t buy the act, he could seem like any other caddish, entitled man.

If people are hesitant to use such strong language today, it is probably because they feel guilty speaking ill of the dead. Novelist Anakana Schofield recently made this point in one of the few harsh essays on Cohen that’s been published in the last two years: “Be very careful challenging opinion on Leonard Cohen. It’s like bringing up someone’s ex-partner with a mistaken warm smile on your face.”

This perhaps wouldn’t be the case had Cohen lived past his 82 years, long enough to witness the election of Donald Trump, the fall of Harvey Weinstein, and the public reckoning about types of misbehaviour we’re no longer willing to put up with. The #MeToo moment isn’t only about sexual misconduct; it’s also about how a certain kind of male persona — the one we’ve variously called the player, the libertine, or the lothario — created cultural expectations about how men might be permitted to act and what women should be expected to tolerate. Would Cohen, who, at times, embodied the lothario identity, have survived such a reckoning? Or would he have faced uncomfortable questions about his art and legacy?

Most of us have a need — morally indefensible yet all too human — to not see our heroes get taken down. And Cohen is, for me, the ultimate hero, a man who defined what it means to be both a Jew and a humanist in the world today. There isn’t a single Hebrew or Aramaic prayer that binds me to my Jewish identity as strongly as Cohen’s lyrics do. And so, like my friend, I feel a guilty sense of relief when I consider that, by dying when he did, Cohen saved us all an awkward conversation.

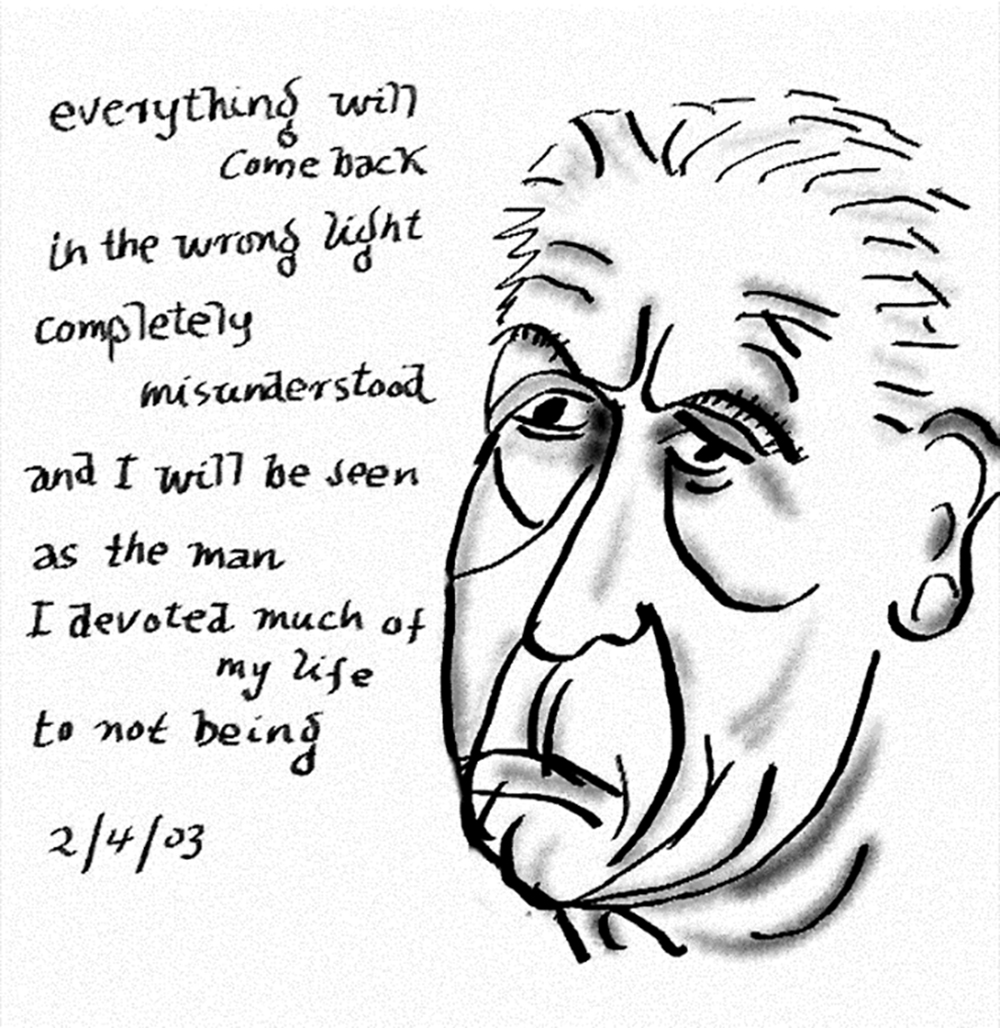

But the reckoning may be coming anyway. Although the dead get a temporary pass, they aren’t immune from criticism forever. Plus, to whitewash Cohen’s legacy is to self-censor, and Cohen opposed censorship in all its many forms. An honest look at him would acknowledge those aspects of his persona that, when seen from the vantage point of 2018, don’t hold up so well. It would also acknowledge that these same elements made him compelling and groundbreaking. They are as essential to his controversy as they are to his charisma and his art. We must find a way to hold all of these thoughts in our heads.

•••

According to a Maclean’s article from 1978, Cohen decided to become a songwriter while watching strangers fuck. He and a partner were at Toronto’s King Edward Hotel in 1965, and the door to the adjoining room was open. He started singing the lines of his poems, adjusting his rhythm to the movements of the lovers next door. In that instant, he had a revelation: perhaps he could sing for a living. (His partner wasn’t so sure.)

In the decades before Madonna and Prince, explicit sexual references didn’t have much of a place in pop music. Artists used innuendo but only Cohen would blatantly describe getting a blowjob on a messy bed. For him, sex was sweaty, dirty, and unmistakably human. This erotic candour invited the charge that he objectified women — that he depicted female subjects as bodies to be lusted after, worshipped, and in their absence, missed. Of course, one might object that a pop song isn’t the ideal medium with which to depict human complexity, but Cohen’s literary writings didn’t always do better.

He wrote two novels, which surely drew the most criticism: The Favourite Game, a racy coming-of-age story, and the surreal Beautiful Losers, with its long passages about male desire and its depictions of sexual violence. The female characters can be manipulative, naïve, debauched, and secretive, but they aren’t always fully realized. “Cohen’s women run to an ideal of romantic bliss or torture, ecstasy or pain,” critic Ezra Glinter wrote in the Paris Review. “They are mirrors for Cohen’s own feelings.” In a 1972 essay collection compiled by Montreal professor Margaret Anderson, one contributor, Dagmar de Venster, put it more harshly: “Do you have an orifice and a pair of breasts? These are the essential if not sole requirements for a female character in a Leonard Cohen novel.”

“If we are to honour the Cohen legacy, we should at least try to consider it in full, taking the bad and the icky along with the good.”

Add to this criticism the fact that Cohen’s behaviour wasn’t always exemplary. While dating Marianne Ihlen — the Norwegian woman on whom the song “Marianne” is based — he put her and her son up in a New York flat, so he might carry on his work, and his affairs, in peace at the Chelsea Hotel. He was equally aloof in his relationship with Suzanne Elrod, with whom he had his two children. “Leonard Cohen related to women as sex objects,” writes the philosopher Babette Babich, “and that also means that he related to his wife when he married as do most men…that is to say, not at all directly but obliquely via his children, and eventually, so it goes with wives and first loves, forgetting them altogether as he moved on.” (Cohen and Elrod were never technically married, but he thought of their separation as a “divorce.”)

There’s an argument to be made that none of this personal information is relevant to Cohen’s legacy. An artist’s life is his life, and if Cohen’s narcissism and romantic selfishness make him a bad man, where does that leave the rest of us? The problem, though, is that Cohen’s private affairs weren’t really private at all. They were folded into his celebrity mythology. The cover of his fifth album, Death of a Ladies’ Man, depicts him flanked, as on a vintage James Bond poster, by two women, one of whom is Elrod. On records and in interviews, he nurtured his Casanova reputation, situating himself as a poetic foil to the era’s more prosaic womanizers: Warren Beatty, say, or Hugh Hefner.

Perhaps the Leonard Cohen persona is one of those cultural artifacts of the ’60s, like space-age clothing or wood-panelled cars, that simply hasn’t aged well. And yet Cohen’s most explicit songs — the ones that got him accused of objectification — also have a kind of spiritual charge. In his music, sex and religious mysticism are entwined like bodies under the sheets. As a young man, Cohen studied the Bible and wrote with rabbinic seriousness. He once told an interviewer that he created poetry, and, by extension, music, with two purposes: to seduce women and connect with God.

The second part of that statement was surely as true as the first. There are many Jewish celebrities, but few were Jewish the way Cohen was. Sure, Lenny Bruce was vulgar and Joan Rivers neurotic, but Cohen’s religious identity was more than an affectation; it was deep, tortured, and scriptural. Even during his short engagement with Scientology and his decades-long affiliation with Zen Buddhism, he continued to identify as a Jew. (Those other pursuits were important, too. Cohen’s life was a never-ending search for spiritual fulfillment.)

His best song, “Who by Fire,” is a rendition of the Unetanneh Tokef, the darkest prayer in a religion with more than a few dark prayers. And “Story of Isaac,” from the haunting sophomore album Songs from a Room, recreates the terror of Genesis 22, in which Abraham, at the behest of a sadistic God, nearly butchers his own son. Cohen’s Judaism was the Old World kind. It evoked an ancient peasant culture in which to be alive was to be in a constant state of fear.

Cohen also drew on another side of Jewish tradition — the charismatic, sensual side, exemplified by the eighth-century prophet Isaiah. “The prophet understood that humankind’s spiritual and sexual yearnings were intertwined,” writes Cohen biographer Liel Leibovitz. “It was an insight that found a ready listener in the adolescent Cohen, himself discovering both yearnings at the same time.”

Is it any wonder that erotic and religious ecstasy seem to flow together in Cohen’s lyrics? In “Light as the Breeze,” Cohen uses devotional imagery to describe an encounter with a woman: “You can drink it or you can nurse it / It don’t matter how you worship / As long as you’re / Down on your knees.” (The “you” is, presumably, a man. Cohen is writing in the second person.) In “Hallelujah,” Cohen’s most famous song, he narrates a scene from the Book of Samuel in which King David sees a soldier’s wife, Bathsheba, washing herself on a rooftop and is overcome with lust. In Cohen’s version, the king’s desire manifests as spiritual elation, restoring his faith in God.

To dismiss Cohen as just another misogynist — as some critics in the ’70s and ’80s did — is to miss the fact that, when writing about sex, Cohen depicted many other things: ecstasy, religious devotion, and those rare moments in life in which we feel we’re communing with forces larger than ourselves.

•••

How do we come to terms with Cohen’s legacy in 2018? The most common answer, it seems, is to focus on the more palatable chapters in his biography. Cohen was at his most controversial during his early– and mid-career phases — the timespan, beginning in the ’50s and ending in the Reagan Era, during which he made the transition from experimental poet to celebrity balladeer — but his story has a surprising third act.

If this period has an official beginning, it is probably February 2, 1988, when, at age 53, he released I’m Your Man, a full-on ’80s pop record, with drum machines and tacky synths. The album has its share of weighty subject matter — meditations on political corruption and the lure of fascism — but it reveals a goofier side to Cohen, which had only been hinted at previously. And there he is on the cover, the melancholy troubadour, eating a banana, because who doesn’t like bananas?

Cohen’s lyrics now had a warmer tone. The title song, for instance, begins with one of his most famous quatrains: “If you want a lover / I’ll do anything you ask me to / And if you want another kind of love / I’ll wear a mask for you.” This lyric is sometimes interpreted as a reference to fetish play, but such a reading seems too literal. More likely, it’s about sexual generosity. How can I please you? Cohen is asking. What kind of partner do you want me to be?

Clearly, by middle age, Cohen had outgrown the tortured-artist schtick. He gave earnest interviews, discarding the cryptic, sometimes confrontational style of his previous media appearances. He publicly disavowed his lothario persona, claiming it was a younger man’s pretension. And he enthusiastically supported the careers of his female colleagues, including his partner, jazz vocalist Anjani Thomas, and his frequent collaborator Sharon Robinson, who appears on the cover of Ten New Songs (2001), which is as much a Robinson album as a Cohen one.

When, in 2004, Cohen discovered that his manager, Kelley Lynch, had nearly emptied his bank account, defrauding him of millions of dollars, he responded in the most magnanimous way possible. Yes, of course, he retained a lawyer, but when legal remedies failed to return the lost funds, he turned instead to the studio and the touring circuit. In 2008, after a decade and a half mostly hiding from the public — sometimes at a Rinzai Zen monastery in Southern California — Cohen hit the road for six years, giving better concerts than at any point in his career.

I caught him in what would be his last Toronto show in 2012. He bounded onstage, swinging his arms above his head like a rodeo king. Over four-and-a-half hours, he played 29 songs, sometimes while kneeling on the stage. He also bantered, danced, and recited poetry to a silent, enraptured audience. At age 78, Leonard Cohen was finally in his prime.

It’s little wonder, then, that when we memorialize him, we focus on this later-life incarnation. The two most iconic Cohen murals in Montreal — a 20-storey-high vertical portrait on Crescent Street and a 9-storey-high rendering in the Lower Plateau neighbourhood — depict him in old age, looking dapper, wrinkled, and munificent. This is the Cohen we remember best, surely because he was with us so recently, and also, perhaps, because this version of him can be easily reconciled with the politics of 2018.

But, if we are to honour the Cohen legacy, we should at least try to consider it in full, taking the bad and the icky along with the good. The earlier half of his life was every bit as influential as the latter part, and it’s hard to imagine one existing without the other. Pop music is a younger person’s game. We wouldn’t have paid attention to middle-aged Cohen had we not already fallen for him when he was in his thirties. And he couldn’t possibly have repudiated his ladies’-man persona had there never been such a persona to repudiate. Cohen’s romantic exploits were a secular counterpart to his lifelong spiritual pursuits. He was always searching, seeking new connections, both erotic and divine. You needn’t admire this side of Cohen, but you may find yourself relating to it all the same.

I don’t need my heroes to be elevated, posthumously, to godlike status. Human beings are sufficiently compelling. But if we’re going to turn Cohen into a deity, I’d rather he was the Jewish kind: not the heavenly father of the evangelical imagination but rather the first testament God, who is at times wise and loving and at other times mercurial and selfish. This deity is, ultimately, inaccessible, which is what humans become after they die.

The most memorable piece at the Montreal exhibition was a work by photographers Carlos and Jason Sanchez, who used holographic technology to create a 3-D representation of Cohen. The viewer stands in a tidy room and looks onto a veranda where Cohen sits staring into the dusk. It’s impossible to say how old he is. You feel his presence but never see his face.