The G.I. Joe with Kung-Fu Grip

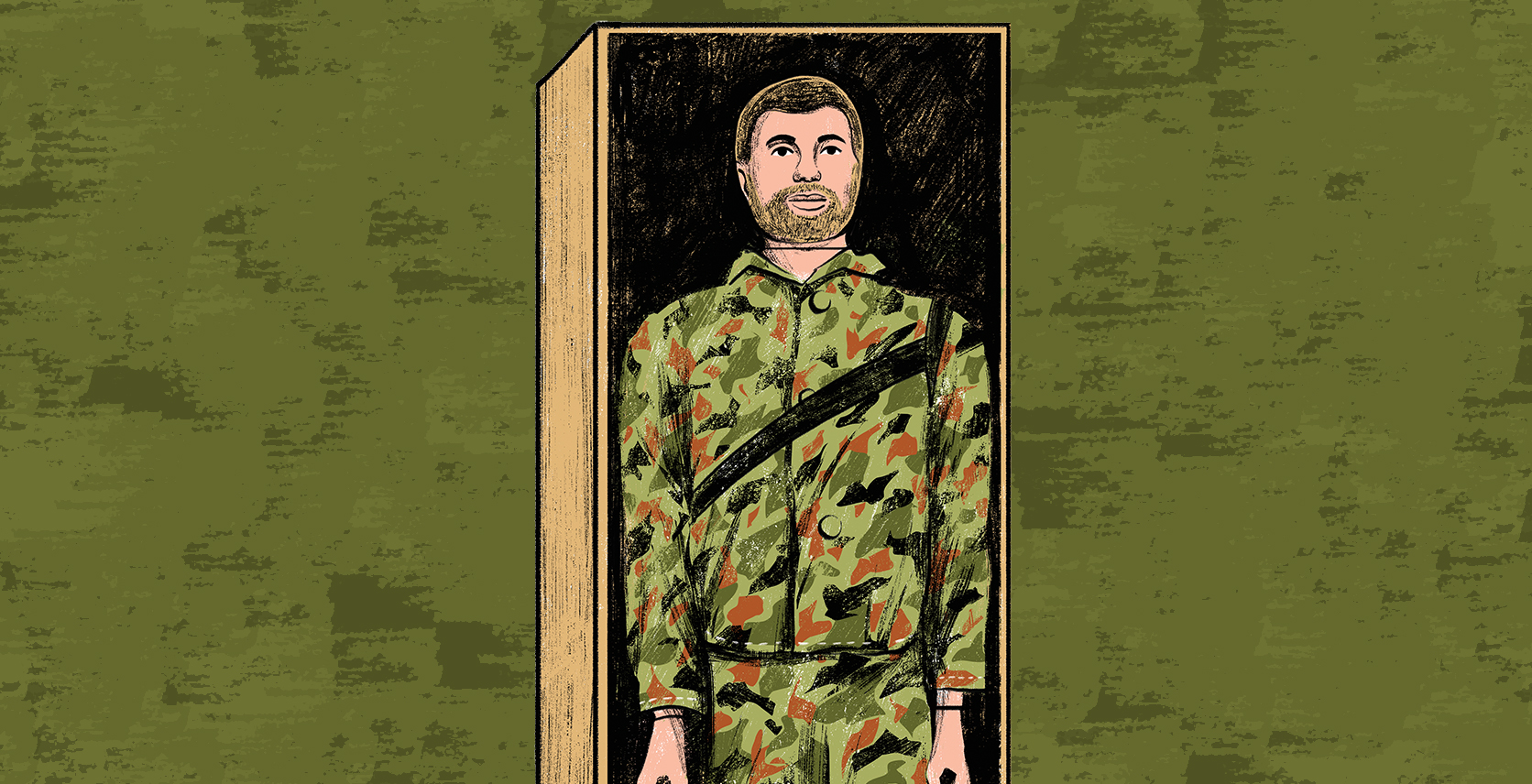

All that is left of the action figure is a camo jacket. Pinned inside a shadow box for safekeeping, it sits on a bookshelf collecting dust. It was 1973, Simpson’s toy department, when I first saw G.I. Joe with Kung-Fu Grip. Its hands, cupped and half-open, urging me to choose it over all the other toys. One other thing drew me to this toy. My father, an immigrant who had left the Azores in 1956, had served in the Portuguese army, as all young men were mandated to do, and my uncles had gone off to fight in the Portuguese Colonial War in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau. All the stories they kept secret would come to life with my G.I. Joe in hand. My father would be pleased, or so I thought.

I was six, a sensitive boy who didn’t exude the rough-and-tumble boyishness my father wanted in a son. He’d drag me away from my sister and her Easy-Bake Oven, ask me to go outside and play hockey with the other boys. He’d often press my pinky down to the side of my cup and always corrected the way I sat — a man never crosses his legs, he’d say. So I knew when I saw the 12-inch figure, its dark complexion, rugged life-like beard and hair, the glint of its dog tags tucked in its shirt, my father would be pleased. But the sting of his rebuke — boys don’t play with dolls — chased me to another aisle, left me confused and dazed. My mother stood up to him, but he blamed her for the way I was turning out.

One night, a few days later, my mother sat on my bed. She tucked me in, looked around the room trying to catch words in her throat. Reaching under her apron, she placed G.I. Joe on my pillow. “I got rid of the box,” she whispered. I knew then that the secret ceremony should remain between us.

Time passed, and so did my interest in playing with action figures. I grew up and abandoned my G.I. Joe, relegated it to some dresser drawer — graveyard of toys.

My mother died when I turned 30. Sifting though her personal belongings, I came across a shoe box. Inside, I found G.I. Joe carefully wrapped in tissue paper. Balancing the figure in my hand, feeling its familiar weight and shape, I was overwhelmed. What we shared was far more precious than a toy.

And so when my eldest son turned five, I was ready to gift him my G.I. Joe. I placed it in his hands and told him to take care of it for me, reminded him it had been a special gift from his grandmother to me. Later that day, my wife confided in me that our son didn’t like the G.I. Joe and was afraid to tell me. I woke the next morning to see the floor littered with nubs of pink plastic. The dog had found a toy in G.I. Joe, gnawed away at it until all that was left was G.I. Joe’s camouflage jacket.

It was convenient for me to think I could pass on part of my story to my son. I wanted to reclaim something that had been lost. Instead, what remains of my mother’s gift is the certainty that I can never reclaim the thing I had lost — that in trying to do so, I am simply turning memory into fiction.