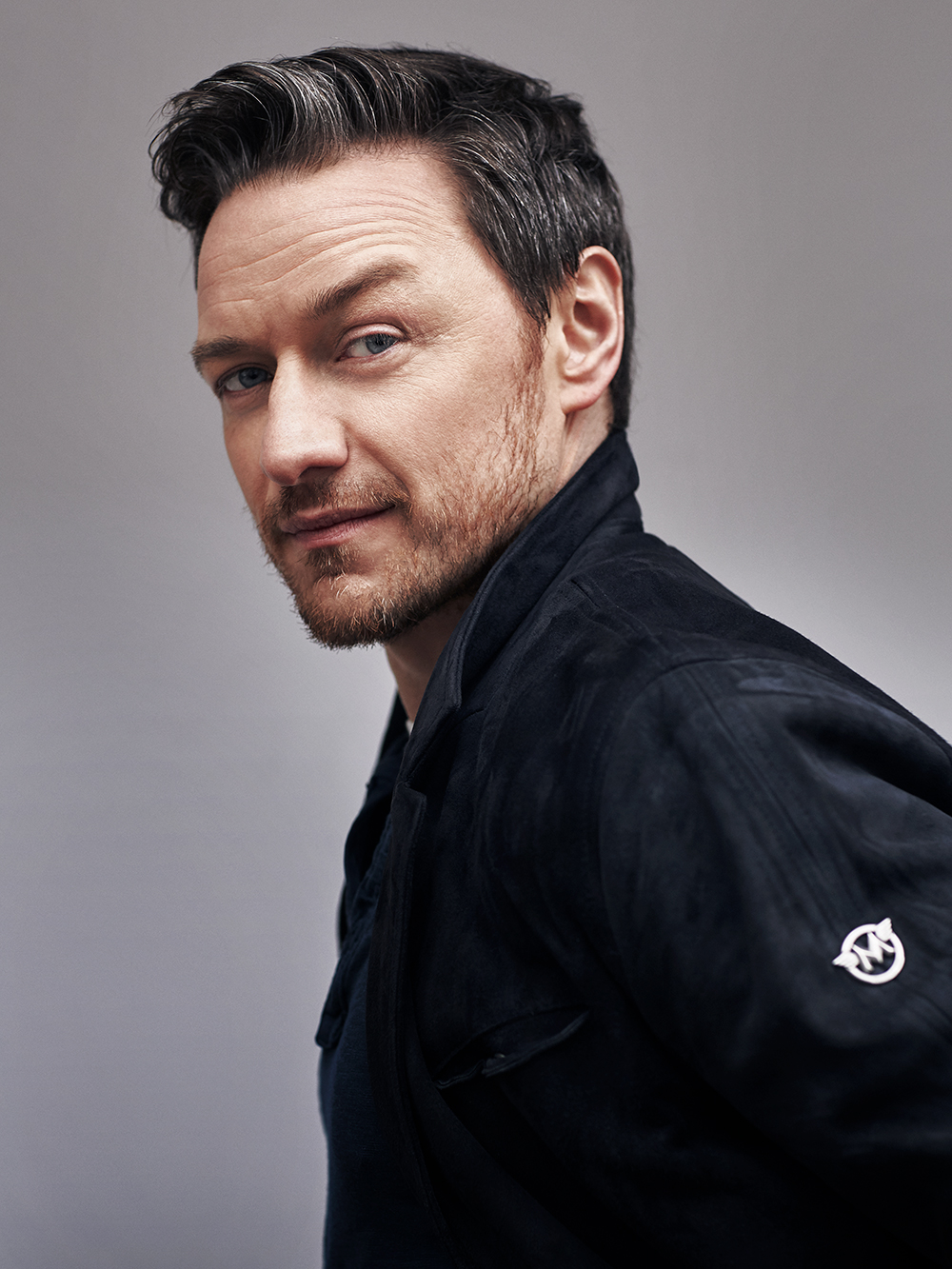

James McAvoy Wants to Make You Feel Something

James McAvoy wants to move you. The Scottish actor, recently 40, has enjoyed wealths of box office success — the big superhero epics he’s starred in have earned hundreds of millions of dollars worldwide. His talent as an actor has been effusively praised — his more serious efforts, in sophisticated costume dramas and weighty prestige pictures, have yielded awards nominations and an abundance of critical acclaim. But what he craves, what he lies in bed at night and privately yearns for, is simply to stand before an audience and watch them writhe and squirm. “I want to make them laugh, I want to make them cry, I want to make them gasp,” he tells me recently. “I want to hear somebody in the crowd go ‘aw, fuck,’ or ‘no fucking way!’ It feels powerful. That’s my favourite thing.”

McAvoy has seemed to glide through Hollywood frictionlessly, gravitating to interesting projects and surprising, even counterintuitive roles. How many other actors could you picture playing an alcoholic cop (as he does in the Irvine Welsh adaptation Filth), a villain with dissociative identity disorder (as he does in M Night Shyamalan’s Split and its sequel Glass), and psychic Professor Charles Xavier (as he has in a series of films beginning with 2011’s X-Men First Class, including this summer’s upcoming Dark Phoenix)? How many other actors could you picture taking to all three so naturally that each seems the role he was born to play? This fall he will be a domineering aristocrat in a British fantasy series and a man terrorized by a demonic clown in an R-rated slasher. How’s that for versatile?

But as McAvoy points out, even if an actor is capable of variety, “you don’t get to choose your career.” Actors get pigeonholed; you can only accept the parts you’re offered. “You’re very much at the mercy of what comes your way,” he explains. When he tried out for Filth — some producer was intrigued by “that guy who usually plays nice chaps,” he says — Irvine Welsh thought McAvoy was “too nice” for the role of a misanthropic anti-hero. He barely got the part. “If the producers hadn’t managed to talk him into letting me read for him, this whole avenue of work that I’ve been exploring for the last six years might never have happened,” he says. “It’s all twists and turns and Sliding Doors stuff, you know what I mean?”

“Being ready doesn’t mean, like, I’ve spent three months sitting on a fucking mountainside contemplating the character, you know?”

His next transformation arrives this September, when we will see him as the adult iteration of Bill Denbrough, the plucky kid who banished evil clown Pennywise to oblivion in 2017’s It. A sequel to the hugely popular Stephen King adaptation, It Chapter Two is McAvoy’s first proper horror movie, and something of an unusual choice for an actor best-known for prestigious dramatic fare. For him, there was never any question of whether he would like to be involved in the film. All it took was hearing from co-star Jessica Chastain, with whom he appears in Dark Phoenix, that It director Andy Muschietti was considering him for the part. “I was just like, ‘I’ll do that in a heartbeat. In a heartbeat,’” he laughs. “I just love that story. I loved the movie as a kid. It was an easy yes, just on the strength of Stephen King.”

Most yeses aren’t so easy. When McAvoy is offered a part, he’s discriminating — he reads a lot of scripts, and he’s particular about what he’ll commit to, especially in recent years. Though he’s worked with several maverick auteurs — your Danny Boyles and M Night Shyamalans — he swears he isn’t swayed by who’s behind the camera. “I’m not that bothered about directors to be honest,” he says. Some actors, he’s noticed, will “work with a director just because he or she’s a good director,” even if they “don’t have a great part.” McAvoy couldn’t imagine doing the same. “That’s one approach. That’s a strategy. That’s your wish. But it’s not mine. I want to feel like I’m doing something, and the writing’s the most important thing.”

Directors, McAvoy says, can be “fucking control freaks.” Best case scenario, if the director’s great, they’ll make the movie better. Worst-case scenario they don’t matter at all. “Is the script gonna help me? No? Then I’m not gonna do the film.”

For McAvoy, writing is everything: “the story’s the thing,” he likes to say. He’s not an actor who gets overly theoretical about his work; he prefers to stick to what’s on the page, and for that reason, what’s on the page had better be pretty damned good. “If it’s not clear from the story what I should be doing, then the scene’s not good enough.” Research and theory, all that method acting stuff, doesn’t work for him. “It’s like when you’re telling a story in a bar to a bunch of people,” he says. “You don’t stop and go, ‘hey, could you all go away and do some research so I can tell my story,’ or, ‘I did lots of research on this story so I really understand it.’ The story itself works or it doesn’t.”

In fact he finds he only does research, he says, when “the script isn’t very good.” “When I’m really going deep into the hidden depths of a character’s past or I’m going exploring real-world parallels and spending months doing it, it’s because I should never have done this movie, and it’s shit, you know what I mean?”

Of course, there’s more to great acting than simply showing up on the day of the shoot and reading what’s on the page. Acting takes real work, and McAvoy knows better than anyone how demanding that work can be. He remembers when Shyamalan rang him up and asked him to be in Split — after Joaquin Phoenix dropped out, with just weeks to go before the start of production. “It was crazy last minute,” he recalls. “I don’t know if I’m going to get all this work done, and we’re shooting real soon, and I just hope I’m fucking ready.” He wants to be clear on this point: you have to be ready, and being ready “means very specific things, like big, fundamental shit.” Being “ready” or “prepared,” he says, “are nebulous words that actors get quoted as using, but they mean something.”

“Being ready doesn’t mean like, my soul is affixed because I’ve spent three months sitting on a fucking mountainside contemplating the character, you know? Being ready means do I know how he walks, do I know how he talks, do I know what he wears, do I know what his worldview is. That’s it. That’s preparing.” These things can’t be improvised, or can’t be improvised well. And for Split, he “just did not know.” “I thought I was going to be winging it.”

In retrospect, he describes the Split situation as an “attractive risk.” It’s the kind of thing that thrills him — the challenge is whether he can pull it off, and in that case, he admits he had doubts about whether he could.

McAvoy is well aware that not every part can be an envelope-pushing achievement, that not every movie he signs on for is going to test his skill. He’s got bills to pay, after all, and every movie star is entitled to do what he will. “I’ve done stuff in the past where it wasn’t good enough,” he says. “I made an agreement with myself awhile ago that I’m not gonna do that again.” He pauses to reflect. “I say that, but then again, ten years from now I might have no money, and I’ll fuckin’ do anything.”

McAvoy is proud of the work he’s done in the X-Men films, and he stands by some of the “really interesting things” they did with his role as Charles Xavier in Days of Future Past. Sometimes being a superhero, he says, “can be a real acting workout.” Yet he’s honest with himself about the limitations of a series of big tentpole films. “In terms of acting, you’re maybe being a little more generic,” he says. “You’re maybe playing a little more middle of the road. Your instincts are curtailed by a middle of the road tendency in bigger movies. And that actually makes it harder to act. It makes it harder to do your job, which is to be interesting, to be compelling.”

He can be thoughtful, even ruminative, on this point. “Why are we on screen?” he asks rhetorically, thinking about his work in Dark Phoenix and the X-Men saga. “I know it’s just a summer blockbuster, but we’re here to reflect humanity. That’s what movies are for — to show a reflection of ourselves in some way, and to tell stories about ourselves, so we can cast a light on what it’s like to be alive and what it’s like to be human.” Yes, even summer blockbusters have that power. “That’s what fucking films are for! That’s what stories are for.”