Exploring the Sonic and Spiritual Appeal of Classic Hi-Fi Gear

A few weeks ago, I arrived home guarding a plainly wrapped record under the wing of my forearm. Spiriting it through the front door, I stood in front of my Dual CS 505 turntable — a platter that has wheeled alongside me for the better part of 30 years — and unwrapped the test pressing of the new Rheostatics album, our first in 15 years, and thus a shade heavier in the life-significance department.

Placing it on the wheel with two hands held to the outer cut of the vinyl, I popped it over the spindle and gently moved the turntable’s needle to the edge of the record. I stood in front of the modestly priced pair of Energy speakers I’ve trusted my entire life, over which an entire oeuvre of Rheostatics records has been played, and let the sound come to me. I wanted to experience our latest music as a listener would, and I knew that these speakers wouldn’t lie.

The quest for this bond between listener and audio equipment — this trust in your stereo to play back sound as it’s meant to be heard — is part of what drives audiophiles to seek out ever-more elaborate and expensive setups. But really, you don’t have to own a $100,000 turntable to love your music player. People still feel a strong allegiance to that case-rattling Sony Walkman clipped to their belt in Grade 11; that 8-track in the fake-wood dashboard of their parents’ sedan; that small pair of pocket speakers they fed into an early laptop; or the jukebox in their grandpa’s workshop, which yielded two tunes for a humble quarter.

All of these — not to mention a little thing called the iPod — are proof that pure sonic fidelity is only a part of a good audio player’s appeal. Sure, there are diamond-cut vinyl needles made by Japanese sword-makers that possessed a mythic reputation in early New York hip hop deejay culture. But there’s also, well, a trusty Dual CS 505. The two sound wildly different, yet both can still inspire powerful emotions. Which is why, in 2019, we’ve reached a crossroads where elite modern sound technology now shares oxygen with boutique shops that trade in cassette manufacturing and duplication. The whole realm of audio is swirling forward, all the while circling backward — one retro-inspired new wave cresting over another.

Which raises the question: what exactly does good audio even sound like in 2019?

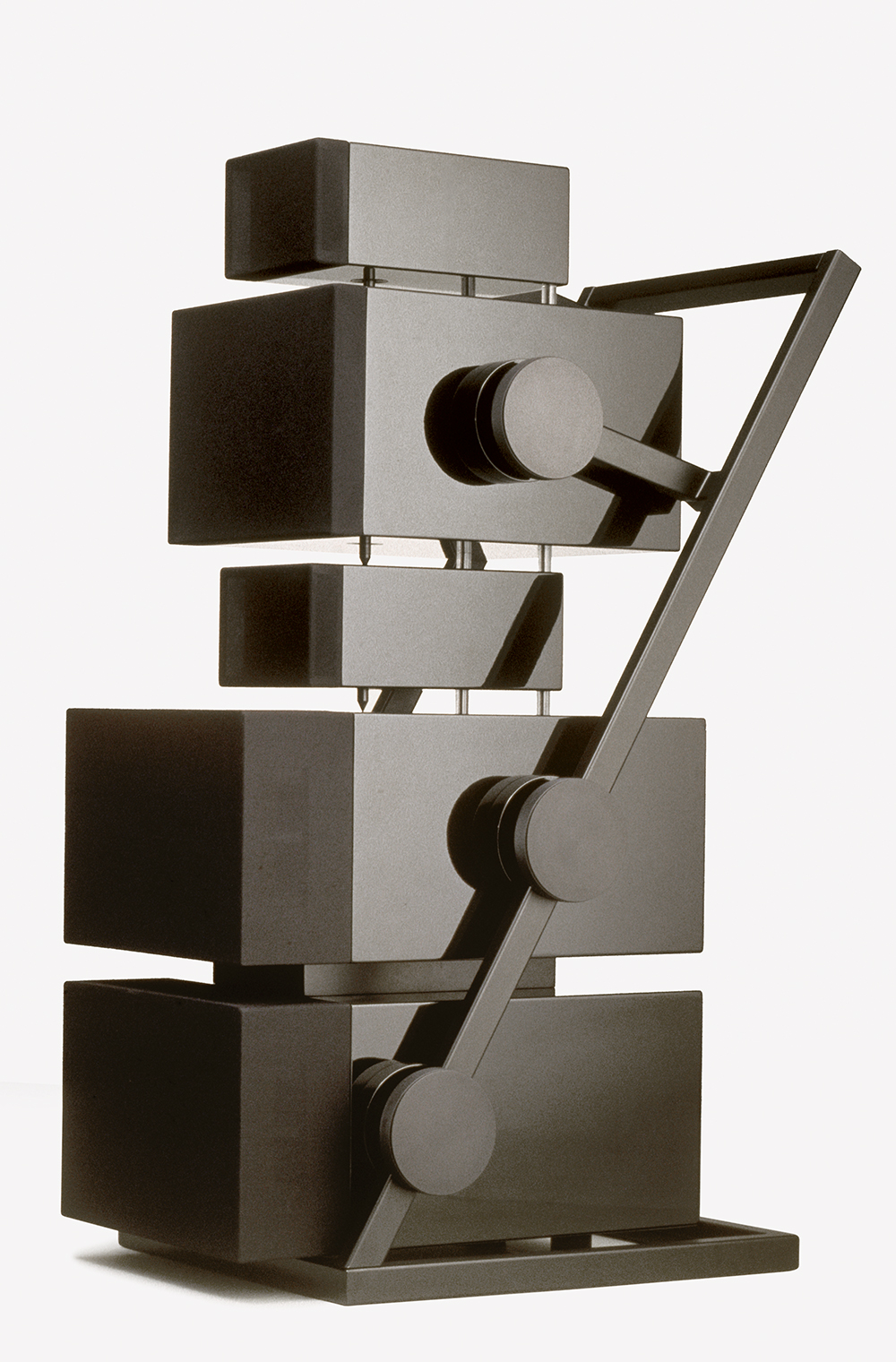

Apologue Loudspeakers by Goldmund, 1987.

Thanks to the easy availability of music today, people are absorbing more of it now than ever before. The act of “listening” has come to dominate our culture, with wireless earbuds now a standard part of any walk down the street. Yet while we have gained the undeniable luxury of being able to summon the sound of music everywhere we go, it’s possible that getting here cost us some crucial aspect of our sense of hearing. We made music more accessible, but we also lowered our standards along the way.

Todd Michael is the head of loudspeaker design and R & D at Yorkville Sound. He designs — and his company builds — the entire range of IMAX speakers for the world. Michael listens to new, elite, and monstrously large audio systems all day long. To hear him tell it, no matter how much respect we now pay to music, we’re increasingly listening to it on inferior equipment: namely, Bluetooth speakers, and earbuds that play heavily compromised sound files.

Olive Series Audio Equipment by Naim Audio Ltd., 1989.

“In our industry,” says Michael, “there are three things that people want: smaller, lighter, and louder — and while we’re at it, cheaper. In recent generations, quality has been forgotten.”

In my home, we have several options for listening — one being a 1973 AMI jukebox that I bought for my 50th birthday when it appeared online after a long stay in a Montreal hardware store. Most of the time, my teenage daughter reaches for my portable Sony wireless speaker — arguably, the most compressed-sounding piece of equipment in the house.

“Back in the day when home stereos were a thing, companies aspired to make them both look and sound good: JBL, Hartsfield, and the EV Patrician box,” Michael says. “But physics tells us that the smaller the speaker, the weaker it is. Today’s small speakers lose output, sound quality, and directivity control. Bluetooth is made for convenience, not fidelity. You buy Beats because of who’s wearing them, and Bose because of how small it is.”

Mind you, all is not lost. The loyal followings developed by new record stores are a shining example of the analog revenge being mounted against the trend toward digital listening.

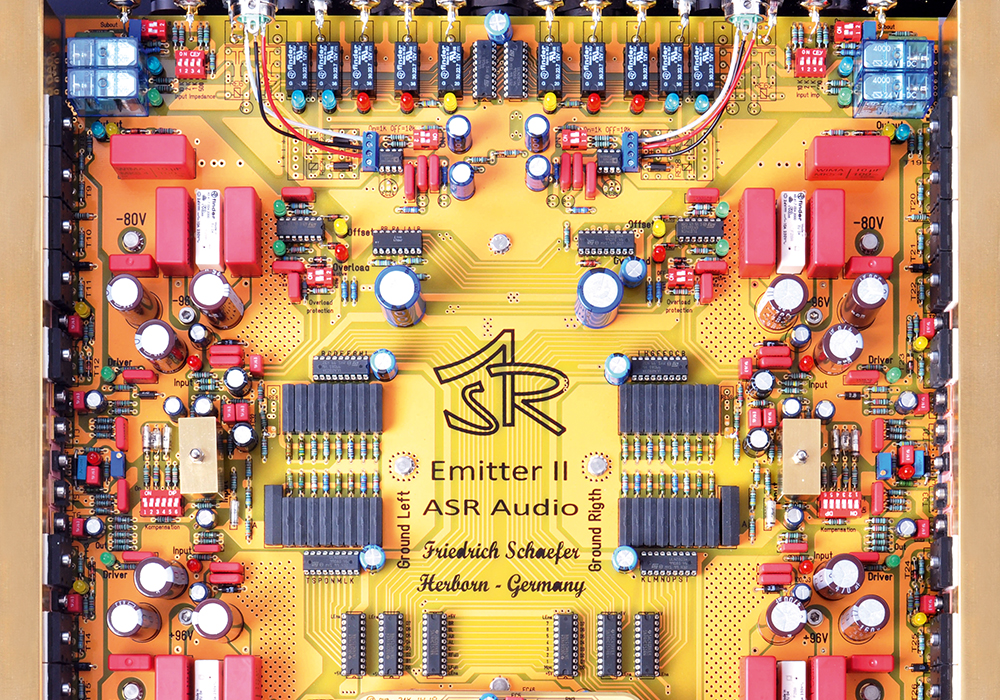

Emitter II Exclusive Amplifier Interior by ASR Audio System, 2017.

Mark Elias runs Soundstage Fine Audio in Waterloo, Ontario. His vocation is the pursuit of fidelity — and increasingly, he’s not alone. “Thirty years ago, you couldn’t find five fine audio shops in Ontario. Now there are five in just Toronto,” he says. Similarly, Elias notes, there are now over 400 turntable manufacturers worldwide. The shopkeeper takes no small degree of pleasure in showing customers what a bass drum should sound like, or how one particular set of speakers better honours the veracity of a singer’s voice. “People have always wanted music to sound good, but because of what the climate is like today, perhaps they want it a little bit more.” Good sound has somehow become an act of rebellion — a way of setting yourself apart.

Amid this surge in nostalgia for more exotic home stereo equipment arrives Phaidon’s latest tome, Hi-Fi: The History of High End Audio Design. The book begins with a rumination on Frenchman Clément Ader, who pioneered the transmission of live opera — for a hefty cost — over telephone lines, and Thomas Edison, the inventor of the phonograph. It dwells a moment longer on the years of recorded sound’s nascence before leaping to the fun stuff: stereo’s heyday of the ’60s and ’70s. This section is a stereo fetishist’s wet dream, packed with remembrances of our society’s former listening habits and apparatuses.

I still remember the first all-in-one Electrohome stereo cabinet delivered to our home and carried down the steps into the carpeted basement TV room. It had an 8-track player, a cassette deck, a turntable, and a radio all built into it, with speakers cross-beamed with wood on either side. I remember listening to the first record I bought — Believe in Music, a compilation album put together by the playlist kings at Canadian label K-Tel — with my parents. Both sides one and two possessed a rare power after coming through a chassis of incomparable length. Did it sound great? I don’t know. Do I remember it? Yes.

Hi-Fi: The History of High-End Audio Design, available from Phaidon, $100.

The Phaidon book dwells on the importance of this era, defined by Electrohome, as well as Clairtone and inventions like the 704 Sound Chair and Peter Munk’s Project G, both Canadian designs. The Project G — an unusual stereo that twinned Scandinavian wood design with two speaker orbs bookending the console — was promoted by Oscar Peterson and Tuesday Weld and owned by Frank Sinatra and Hugh Hefner, while the Sound Chair promised “the sound of tomorrow…today” by positioning its speakers at ear-level, built into the seating fabric. Stereo design in the ’60s and ’70s reflected the vibe of its day — frankly, everyone seemed to be making the kind of stereo that a character in a Stanley Kubrick film might listen to.

The book courses through the lives of inventors whose brands have long outlived them — Dr. Amar Bose (an Indian immigrant who grew up in Philadelphia), Etsuro Nakamichi, and Saul Marantz, from Kew Gardens, Queens, who got started in the game by removing his car stereo so he could use it in his home.

Meanwhile, Sammy Davis Jr. was spinning records at a party, Elton John was reclining on his couch with early designer headphones, and a woman in formal wear was feeding 45s into a record player built especially for her car’s dashboard: the Auto Mignon Car Record Player by Philips. If there’s a fantasy that draws people to stereo equipment, it’s the one on display in these images: the music lover looking as cool as an off-duty rock star, relaxing in the warmth and comfort of the home. This introduces another disconnect from today’s experience: traditional stereos invite you to sit down in your favourite chair; Bluetooth devices encourage you to be anywhere but in one place.

Inspiration XS-IIIC Loudspeakers by FM Acoustics.

Although it’s not stated in the book, man’s inventiveness — and, it must be said, fun — with audio technology is driven by the pursuit of “absolute” sound, a term that Elias uses when referencing an influential, and now defunct, magazine by that same name. “I was shown the magazine (The Absolute Sound) by a friend in university with whom I worked in a camera shop, and it really opened my eyes to the technology. Back then, in the ’70s, we’d get our student loans and spend part of the money on a stereo. Later, the people I met in the industry worked obsessively on the technology in pursuit of the idea of ‘absolute sound,’ which is elusive and, as a result, interesting.”

Both Elias and Michael work in the presence of crazy-elite sound systems — one commercial, the other industrial — and their ninja power is to lead listeners and clients to their first truly elevated listening experience. Like musical taste, the way one hears and processes sound is personal. It’s one of Elias’s challenges when it comes to curating and installing $100,000 sound systems in people’s homes.

“Everyone hears things differently, and choosing a stereo system has aesthetic considerations, too. Sometimes when you get the equipment into a customer’s home, you have to modify it or have the customer change the layout of the space for it to sound right. I have some multi-millionaires as clients who buy expensive equipment because they can, but most of my customers just enjoy music and are looking for the best, truest sound.”

Todd Michael agrees that the subjectivity of sound makes his job tricky at times. “You can use measuring instruments to determine what something sounds like, but music reaches people in a very personal way. It’s a black art trying to design something that matches that.”

Statement Loudspeakers by Zellaton GMBH.

Nonetheless, the high-end audio industry continues to reach higher. Even if the ears that appreciate this stuff are now few and far between. Especially because they are now few and far between — truly incredible sound might just be how you win them back.

“A company called Kondo makes handmade stuff that takes months and months to create,” says Elias. “They use only aged silver that has been set for ten years, and they make all their own wiring and resistors. Their stereos create an experience that is at a level I’ve never heard before. You can hear something like how hard a person is plucking a string, for instance. My goal is to get that best-sounding equipment in as many hands as possible.”

To say that Elias goes to great lengths to get the best-sounding equipment is to call Steely Dan a sloppy band. His curation of “personal sound” for customers often involves a long, arduous journey.

Case in point: for one customer, he assembled a rig that included a MartinLogan CLS, an Ayre KX-R preamp, MXR mono blocks, and a pair of MartinLogan Descent subs. The total so far: about $70,000. Then came the moment of luck. Elias found a British distributor who had a 700-pound Clearaudio Statement turntable — normally sold for $110,000 — listed for only £700 because it didn’t have an arm. He paired that up with a Tri-Planar tonearm and a Lyra Olympus cartridge for another $11,000. “We used a monument delivery truck to load it up and unload it on the customer’s porch. We set up the system and spent several hours just adjusting the turntable and cartridge set-up to give maximum fidelity,” Elias says. The final outcome: “The turntable is spooky quiet. On good recordings, there’s no perceivable record noise whatsoever. And the singers and instruments sound life-sized — you can almost walk up and around them.”

So yes, the options at the highest-end level of stereos continue to evolve. Of course, the question remains whether the general public will seek out, or return to, a time like that depicted in Hi-Fi when so many people are content with tinny laptop speakers. Perhaps it’s telling that both Elias’s and Michael’s spirits fall when discussing the future of sound — absolute or otherwise — in our society. Michael is especially fatalistic: “Kids are taught in school about what looks good, what tastes good, but never what sounds good, and that probably isn’t going to change.”

So, as someone whose band is about to release its first new record in 15 years — a record that we have laboured over for two full years — I’m now left wondering about not just whether people will listen to it, but also how they will listen to it — on a vintage Project G? On some niche turntable flown over from England? Oh, and if you don’t like the album? Blame your Bluetooth.