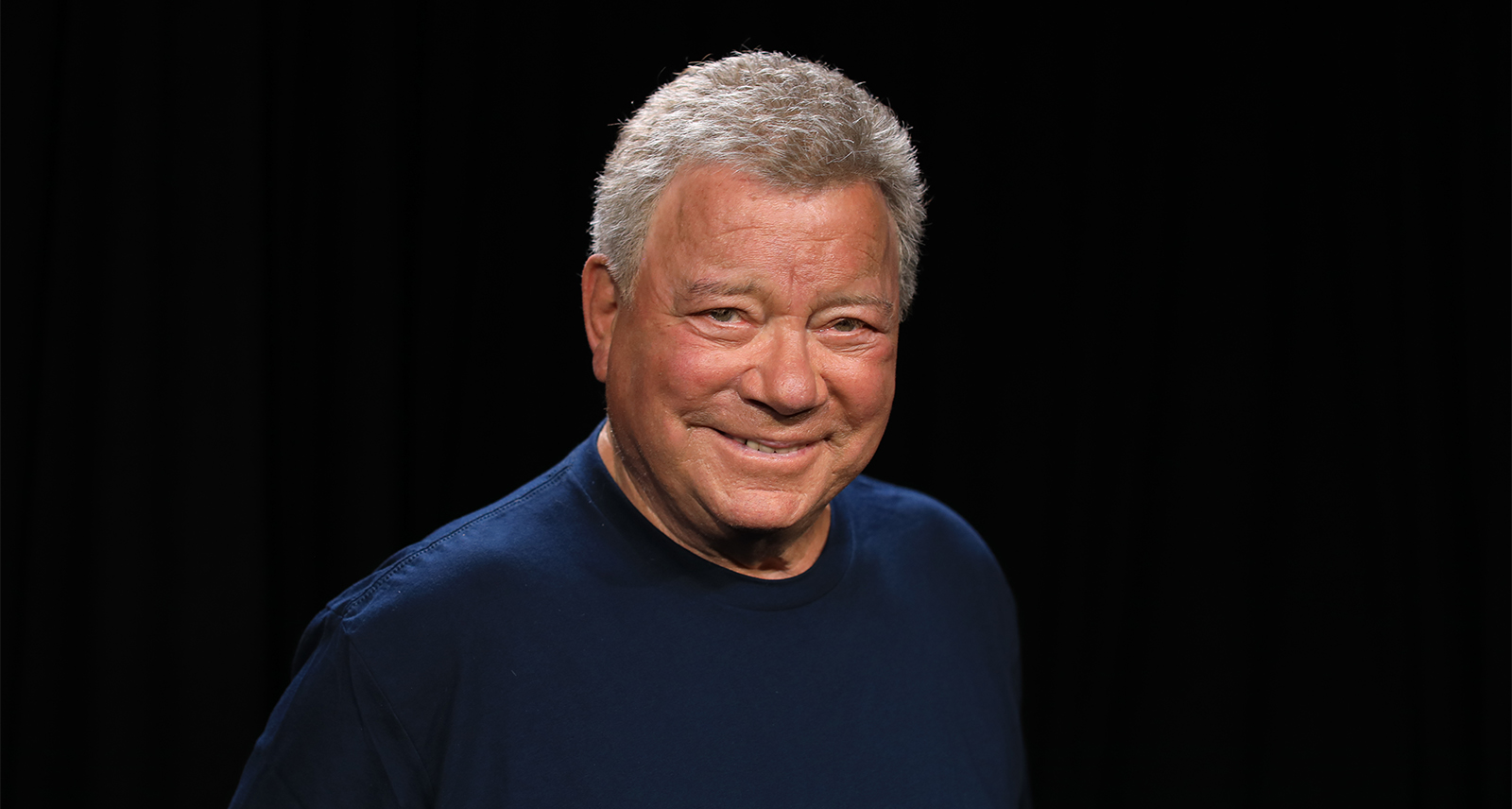

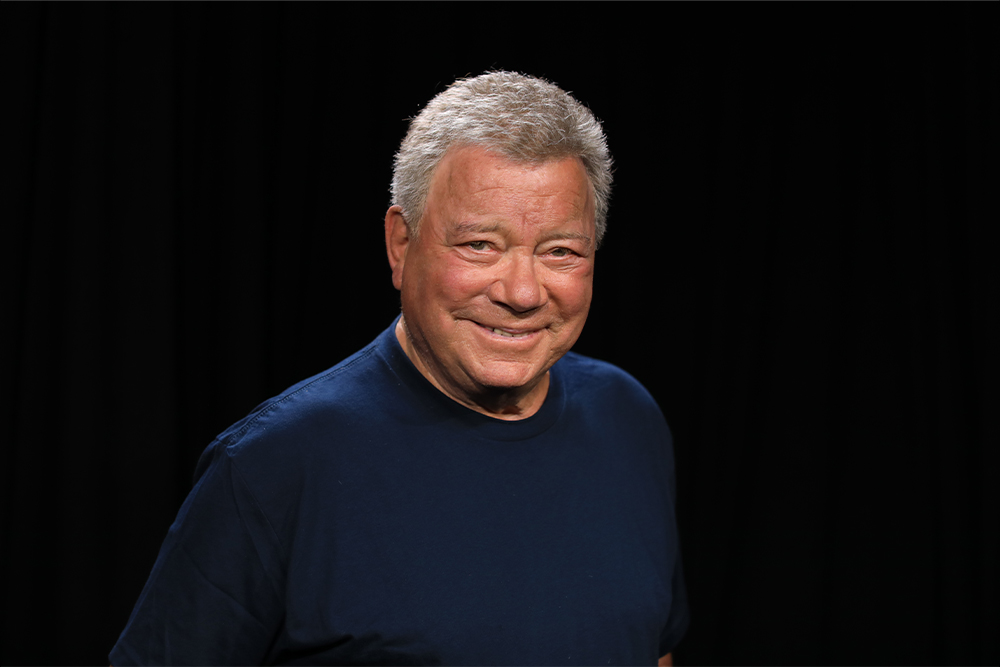

William Shatner on Space Travel, Living Up To Captain Kirk, and Forgetting His Age

When William Shatner became the oldest person to go out into space last fall as part of a Blue Origin sub-orbital mission, he wasn’t struck by the grandeur of it all, as you might expect of a longtime film and TV star captain. Rather, he was struck by the emptiness of space in contrast to the teeming life on the little blue rock he had just left behind. Taking stock of a rare experience he shares with only a few hundred privileged people who have also boldly gone beyond terrafirma, he notes that the beauty wasn’t out there in the vastness of the stars, but in the flawed and increasingly vulnerable planet below.

That’s some of the melancholy wisdom offered up in the nonagenarian Canadian actor, director, author and (unlikely) musician’s new memoir Boldly Go: Reflections on a Life of Awe and Wonder. A whimsical, amiably digressive tour through his many entanglements both eastbound and interplanetary, the book is a profile of a working actor whose Captain Kirk-like thirst for knowledge about the natural world, and its resilience in spite of humanity’s numerous efforts to destroy it, is inextricably linked to his drive to keep exploring new projects.

SHARP recently spoke to Shatner by Zoom about learning to appreciate (and mourn) life on Earth, the cosmic coincidences of his friendship with Leonard Nimoy, and showing up for work no matter the job or one’s age.

I’m struck by how much of your new memoir sounds like utopian science fiction. You say the weeds are made out of the same star stuff as we are. You’re fascinated by the secrets mushrooms hold about communication.

But that’s established scientific fact, not utopia.

What is it about these scientific facts that command your attention?

We’ve walked around as ignorant entities for so long, thinking we’re unique and we’re separate, and the world belongs to us, that we have dominion over it. That’s been pumped into us for so long that we’ve become this arrogant species who’ve destroyed the world. Not only have we destroyed it — we’re continuing with a greater aggression to destroy it even now that we know we’re destroying it.

My devotion to nature is one of awe and wonder. We develop better instruments, and we begin to realize things about which we had no idea before. We learn that we’re more alike to trees than we are unalike. It’s an increasing appreciation of the natural world and how bound up everything is.

As for whether that’s utopian, you want the book to be entertaining. You want to talk in utopian terms and not these dystopian ones so people will read it. But the future is very hazy.

It’s possible — and I believe 90% of what I’m saying, because there’s always a little bullshit — that there’s no such thing as coincidence.

William Shatner on his connection with Leonard Nimoy

Do you think we indulge in science fiction or fantasies about space travel to avoid some of these dystopian realities about climate change?

No question. That’s a very human thing. Let’s not think about the mortgage: let’s go to the movies. Kicking the can down the road is a very democratic thing to do. In a more authoritarian form of government, they might say, let’s ignore it completely. It’s so much easier to say, let the next guy do it. Miami comes to mind with people spending millions on seaside property. They’re building 20-foot walls in anticipation of the oceans rising. The world is filled with people who don’t want to look at reality and do something about it.

You say that your trip to space helped you appreciate the fragility of life on Earth. I’m struck by how mournful you seemed in the return footage. There’s a clip of you overcome with emotion, trying to articulate the experience to Jeff Bezos while the team is celebrating with champagne.

I’ll tell you, about the moment you’re describing, that I went to sit down someplace to try and figure out what it was that was moving me so much. And then I realized I felt a sense of grief for the Earth and what we’ve done to it, and the millions of things that are going and have gone extinct, that took billions of years to evolve. And so, I was in mourning and grief for the Earth. And then as a day or two went by, I realized I had known how insignificant the Earth is and I’d seen examples of it. The insignificance of the Earth and the insignificance of human beings on the Earth amounts to nothing. But the final realization is that we’re aware that we’re insignificant. And that awareness might be what makes us unique.

I was invited to a meeting of some well-known scientists sometime after that, and they played the clip you’re talking about, and at the end of it, Bezos embraces me. And I thought, my God, I’d forgotten that. That there’s love. There is empathy and sympathy among human beings.

We’re all frightened: of death, of disease, of accidents, of Monkeypox. So, there are elements of Captain Kirk that are in me. But there are also elements that I must aspire to, to keep up the front.

William Shatner on being seen as Captain Kirk

You come back to your friendship with Leonard Nimoy throughout the book, particularly in a chapter on human nature, where you speculate that we’re made of different LEGO pieces that can work with or against other people’s natures. What were some of those LEGO pieces you and Nimoy had in common?

It’s possible — and I believe 90% of what I’m saying, because there’s always a little bullshit — that there’s no such thing as coincidence. Leonard and I were born four days apart. He was born in Boston and I was born in Montreal, which are similar cities in terms of their age, in terms of the East Coast artistic scene. He was born shortly after me in a family similar to mine and in a city similar to mine.

He had a very academic approach to acting, isolating moments and beats and so on, which was different from my approach, which was chaotic. I did whatever was there: whatever opportunity presented itself. Leonard, although coming to it differently, had the same professionalism about acting I did. So, when we met and were forced by Star Trek to be in each other’s company, we began a friendship. Everything that happened to him, happened to me, through the three years on the set, and the many more years going to events, making the movies. It was a beautiful friendship. I thought and felt about him like a brother, the brother I never had.

The ending was so peculiar that I grasp at any explanation, one of which is that when you have an illness, when you know you’re dying, you’re not the same person. So that’s what I ascribe his behaviour to in the last several months of our relationship. But for a time, it was like we were conjoined.

Another of your longstanding associations is with Captain Kirk. I wonder if people’s perception of Kirk as a risky maverick isn’t a bit flat. He’s also a Navy guy: solid, strategic. You talk a lot in the book about putting in the time, being prepared for the job, and showing up. How much of William Shatner is in Kirk?

I never thought of it in quite that manner, but I think it’s true. If I use the phrase, “But I’m Captain Kirk” about a situation, I can get a laugh. For example, as the gantry was being readied to be pulled away from the spaceship, the guy who was doing the countdown said, “If you want to get out, you can get out now.” For a moment, I was so apprehensive about the hydrogen and about human error that a part of me thought, Jesus, I’ll get off. And then I thought, I can’t: I’m Captain Kirk. [Laughs] Or people think I’m Captain Kirk, with all those heroic characteristics. I can laugh at it, because I’m a frightened actor about everything. We’re all frightened: of death, of disease, of accidents, of Monkeypox. So, there are elements of Captain Kirk that are in me. But there are also elements that I must aspire to, to keep up the front.

You speak about how your survival instinct has always been bound up with work. How do you maintain that drive to keep working in your nineties?

Well, it’s a process of — what would the word be? — senility, where I forget that I’m 91 and I think, well I could do that. And then I do it and I think, why am I so tired? Because I’m 91, and I keep forgetting. So, the answer is forgetting. You forget your age, you go stumbling on.

May you continue to forget your age.

May I do that until I die. And wonder why I’m dying.