Malcolm Harris on Palo Alto, Masculinity, and Land Back

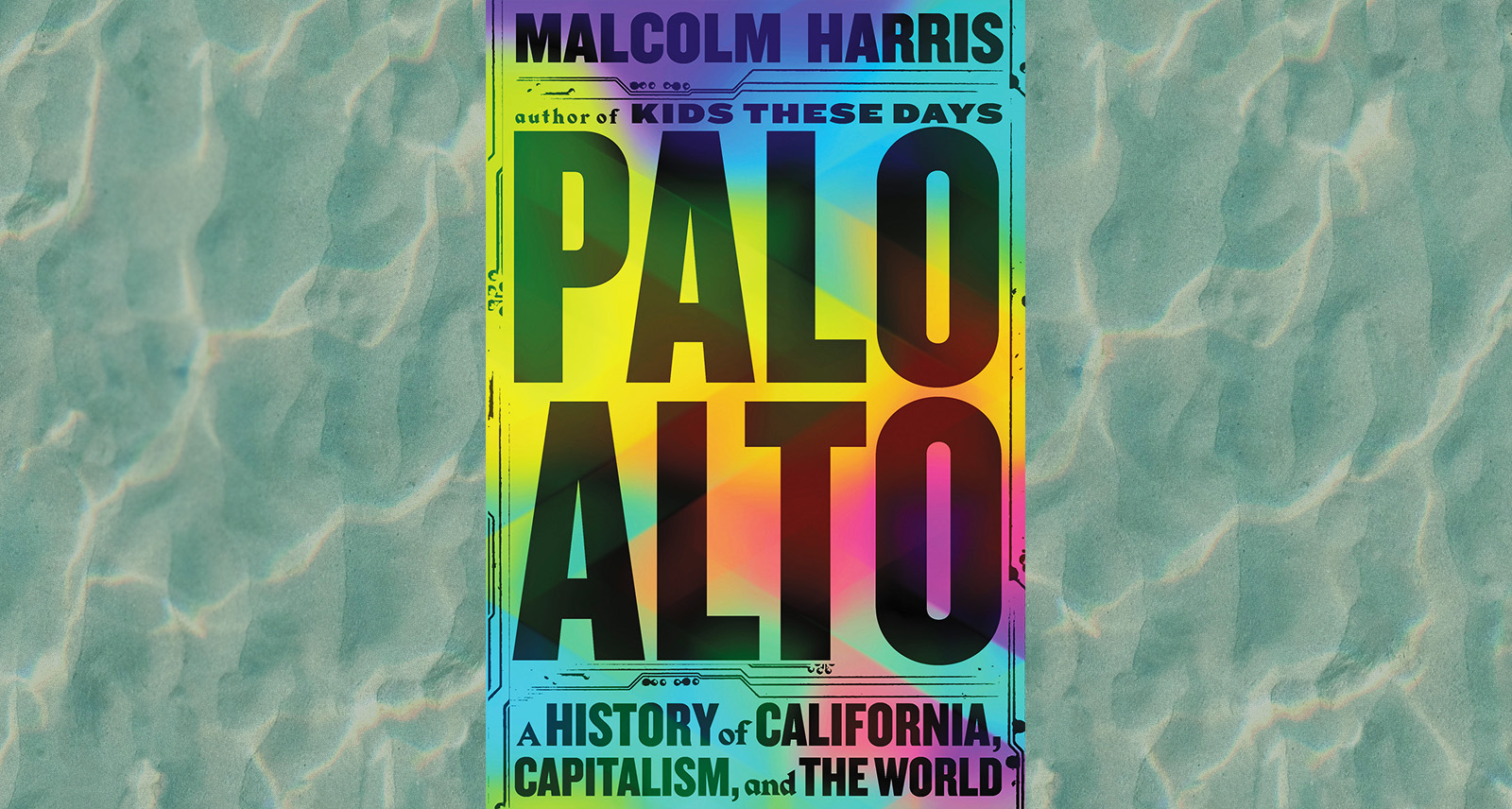

In his latest book, Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World, author Malcolm Harris tries to get to the bottom of what Palo Alto is: “nice,” “haunted,” and “the centre of the world.” Silicon Valley’s pursuit of endless renewal, he argues, has become the status quo for not just this small patch of land in California, but America at large. “If California is America’s America,” Harris writes, “then Palo Alto is America’s America’s America.”

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World is Malcolm Harris’s third and most expansive book. With great insight and a wry sense of humour, Harris charts the relatively short history of Palo Alto, beginning with the Anglo-settler colonialism that began just 150 years ago. Exploring periods of exhausted resources, eugenics projects, and new technologies, Harris’s intersectional approach offers a terrifying, astute, and occasionally hopeful look at the world’s broken core.

SHARP spoke to Harris about branding, esports masculinity, the Land Back movement, and more.

In the book you quote David Star Jordan, who says, “great men live great lives because they’re great; they’re not great because they’ve lived great lives.” That seems to be a recurring theme within the book. What explains this idolatry of the people who live and work in Palo Alto?

It’s great branding, and it’s been the branding for forever: California represents instant limitless possibility and wealth for anyone. This was the branding from the beginning of the Anglo-American settlement. It’s funny that, before then, it represented something very different. It was the last corner of the world that no one managed to colonize effectively. Then it quickly becomes California in the same way that we understand it to be California today as a zone for get-rich-quick schemes, speculation, as well as beautiful weather. And the beautiful weather part is real, right? The ecology of the Bay Area in particular, it’s beautiful and was certainly more beautiful a century and a half ago.

That plays an important role in its history, as people want to move there because it’s nice. Immigrants from Italy were like, “I don’t wanna live in Boston. Where else can I live?” So, they live in California. Also, the business of the place is this branding and reputation, pulling in capital from all around the world. To do that, it has to sell itself as a magical, different place, which it is in some ways it is. There is some truth underneath the myth, both historically and ecologically.

“In the mid-century, you’re talking about the military-industrial complex that is very intentional about elevating what it views as talented, good, and potentially successful young men in particular.”

Malcolm Harris

In the book, you not only chart the evolution of the land and business of Palo Alto, but also this idea of the “ideal man.” We begin with this well-rounded, all-American type character who is smart, rich, and a great athlete. Later on, with men like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, there’s almost a pride in being antithetical to that original ideal. What explains this change?

What you’re talking about is the shift in what historian Charles Petersen calls bureaucratic masculinity to nerd masculinity. And, right now we have an interesting synthesis going on of the two. Bureaucratic masculinity has to do with how these successful men are selected in the system. In the mid-century, you’re talking about the military-industrial complex that is very intentional about elevating what it views as talented, good, and potentially successful young men in particular. It involves not just being smart but also being well-presented, being good at sports, being handsome, dressing well, etc. The whole package, right? These people are literally chosen by administrators of higher education and the military for elevation. It’s really embodied by someone like David Packard. He’s a great example because he’s selected consistently by the powers that be for positions, they basically pick him to start Hewlett-Packard.

With Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, the shift is to nerd masculinity, where you have a sort of collapse of that public system as a result of conflicts in the ’60s and early ’70s, where the solution is too diverge in the U.S. from these public systems and to concentrate privilege and access within private systems; the suburbs, gated community, private schools, more expensive colleges, etc. Steve Jobs and Bill Gates are great examples of that suburbanization, and with that comes the flouting of previous standards of bureaucratic masculinity.

“Watching Facebook fall like fifty per cent in some months, I’m not sure how something like that integrates into their self-conception. Does your self quality just fall by half? Are you half as great as you were before?”

Malcolm Harris

Since they no longer have to appeal to the bureaucracy in higher education or the military – they don’t join the military, they don’t go to college or drop out – they have to appeal to the market. They find success by flouting those previous standards with a new kind of masculinity. Now we have a kind of esports masculinity? They want to be jocks and nerds at the same time. Not just a balance, but both to a really high degree. They want to be jockey jocks and nerdy nerds. You see someone like Elon Musk pretending to be a super computer programmer – when he’s not one and everyone knows he’s not one – but as part of this esports masculinity he has to pretend he’s the best coder at Twitter, because otherwise why would he be in charge? It’s like Jeff Bezos has to be jacked; he has to have a super hot girlfriend; he has to fly on a spaceship, but also be a super nerd. I’m still toying with what comes after nerd masculinity, but I think esports masculinity could work out [laughs].

I find someone like Zuckerberg such an interesting case study, though. He benefits so much from his proximity to power and elitism, while also painting himself as an outsider.

They want a new hierarchy with themselves on top. They pretend to be the type of person who deserves that role, even though it’s really luck and happenstance and has little to do with them as an individual, except that they’re a little mean. You see Mark Zuckerberg fashioning himself like a Caesar Augustus type, down to the haircut. It’s about obsessing over past elite leaders and thinking that he is in this line, and that that’s why he has so much wealth and power is because he is who he is. It goes back to that David Star Jordan quote, right? He’s trying to say, I’m living this great life because I’m a great person. I am a product of my quality and not a product of circumstances. Even though we know that’s false. Watching Facebook fall like fifty per cent in some months, I’m not sure how something like that integrates into their self-conception. Does your self quality just fall by half? Are you half as great as you were before? I’m glad I don’t have to worry about my stock price.

A lot of your critics are taking issue with your conclusion, where you propose that a small piece of land owned by Stanford University be returned back to the Muwékma Ohlone. You’re not pretending to have invented the Land Back movement, but a lot of your critics seem to think you are. Why do you think people are so upset?

Canadians probably have a better sense of it than Americans, just because I think the Indigenous movement is more active in Canada than it has been in the United States, although it’s changing. It’s a continent-wide movement. It’s always interesting to hear what perspectives people have on what that’s meant and how serious to take it and in what way. Some people have taken it very symbolically, some people much less so.

“[Land Back] says we can’t just talk about it with acknowledgements and rhetoric – we have to talk about ceding the land.”

Malcolm Harris

I’m pretty sure the Land Back activists don’t mean it symbolically.

Exactly. The crazy part is that [the history of California] is only 150 years old. That difference [between East and West Coast] is so important. People who don’t take the conclusion very seriously have said, “he says give back the land to Indigenous peoples,” and I said no, I’m talking very specifically about the Muwékma Ohlone. It’s a politically constituted group, I think there are about 500 people and they need a place to live on their ancestral land and Stanford acknowledges it is on their ancestral land.

Stanford not only has a land acknowledgement, but if you go to the “land acknowledgement” page for Stanford University, it has a link about Land Back. It says we can’t just talk about it with acknowledgements and rhetoric – we have to talk about ceding the land. It’s pretty low-hanging fruit. They have 8,000 acres – it should be pretty easy to cede at least the land and money necessary for the members of the tribe to make a life for themselves.

The amount of land you’re suggesting is actually small in context of the colonisation of California.

It’s really just this very bitsy little corner. Compare it to the land that was deeded to the Southern Pacific Railroad, for example, which is the size of Maryland. Their response is, “well it’s a really nice corner.” It sort of gives the game away. They say the land is super expensive. And it’s like, “yeah, you took all the nice parts! You only want to give up the parts nobody wants!”

It’s interesting that this covenant with the Stanfords, with the founders, that the land could not be sold – with some exceptions for transferring to sovereign entities such as the United States government –has been respected, but the ancestral people’s covenant that the land not be sold was never respected anywhere in this continent. I don’t think it’s very complicated.

“It’s funny that the historical memory of these people is so short that they only go back to the ’60s. They can’t even recall the context for this whole thing. The book asks a lot of the reader – you have to actually read it page by page, line by line, or you’re going to sort of misunderstand the perspective.”

Malcolm Harris

The New York Times had a very scathing review of your book, basically taking you to task for cherry-picking quotes. Among them, they suggest you don’t dwell enough on the violence of communist regimes and the millions left dead. How do you respond to this type of criticism?

It’s like a sucker game, right? We all know where it goes – that’s what red-baiting is for. In the book, when I talk about the relationship between the Soviet Union and the United States, I think it’s interesting that the communist movement in California, which was very strong, ends up sacrificing itself to the popular front on the orders of Moscow. That’s not the idea that we have of communists and what communists do, right? [We think of them] as loyalists, unwilling to compromise with capitalists under any circumstances – certainly in the United States, but what we see in California is a shift in policy when the Roosevelt administration recognizes the Soviet Union, which the Hoover administration had refused to do.

Part of that agreement is that the Soviet Union cuts off attempts to forment revolution in the United States, and they do and it kills this movement, basically. It sets the labour movement back in California, and it’s a sacrifice that these radicals are knowingly making to this popular front that’s going to fight Nazism. It’s funny that the historical memory of these people is so short that they only go back to the ’60s. They can’t even recall the context for this whole thing. The book asks a lot of the reader – you have to actually read it page by page, line by line, or you’re going to sort of misunderstand the perspective.

When we see the communist labour organisers in California – when the workers want to push harder and push for more money because they think they might be able to get it, even though it might lead to more death in the fields – it’s those communists on orders from Moscow saying, “look guys, we think this is probably the best bet you’re gonna get, even though it means getting rid of us,” even though that trade was to get rid of the communist unions. The idea that Stalin’s relationship to California is uncomplicated is itself a thin reading of the book. Red-baiting isn’t a truth-seeking practice, so if you wanted to know answers about this history, that’s not the tack you would take.

“Those same values of youth, potential, scale, profit, experimental technology, and disruption that underline the Palo Alto System of horse production … all that continues to underline Palo Alto in the 150 years after the Palo Alto system.”

Malcolm Harris

Since it’s pivotal to the argument of your book, could you explain the Palo Alto System?

It’s important to understand that it’s a metaphor, right? If you go to Palo Alto now and ask about the Palo Alto System, they wouldn’t know what you’re talking about. They might make something up because that’s the kind of people they are, but they don’t know, they don’t know this history. It’s not a literal continuation, but it was this new way [of thinking] that really starts with Palo Alto starting as a horse farm.

The Palo Alto System was a new way of training horses. They built a kindergarten for horses and started running horses as fast as possible as young as possible, which is a revolutionary way to bring up horses. They succeeded in raising more younger, faster horses than anyone in the world. That was the Palo Alto System.

Those same values of youth, potential, scale, profit, experimental technology, and disruption that underline the Palo Alto System of horse production – as well as the disregard for all the good horses that get their legs broken because they’re running too fast and too young – all that continues to underline Palo Alto in the 150 years after the Palo Alto system.