Trying to Imagine What Silence Looks Like: On Losing Prince

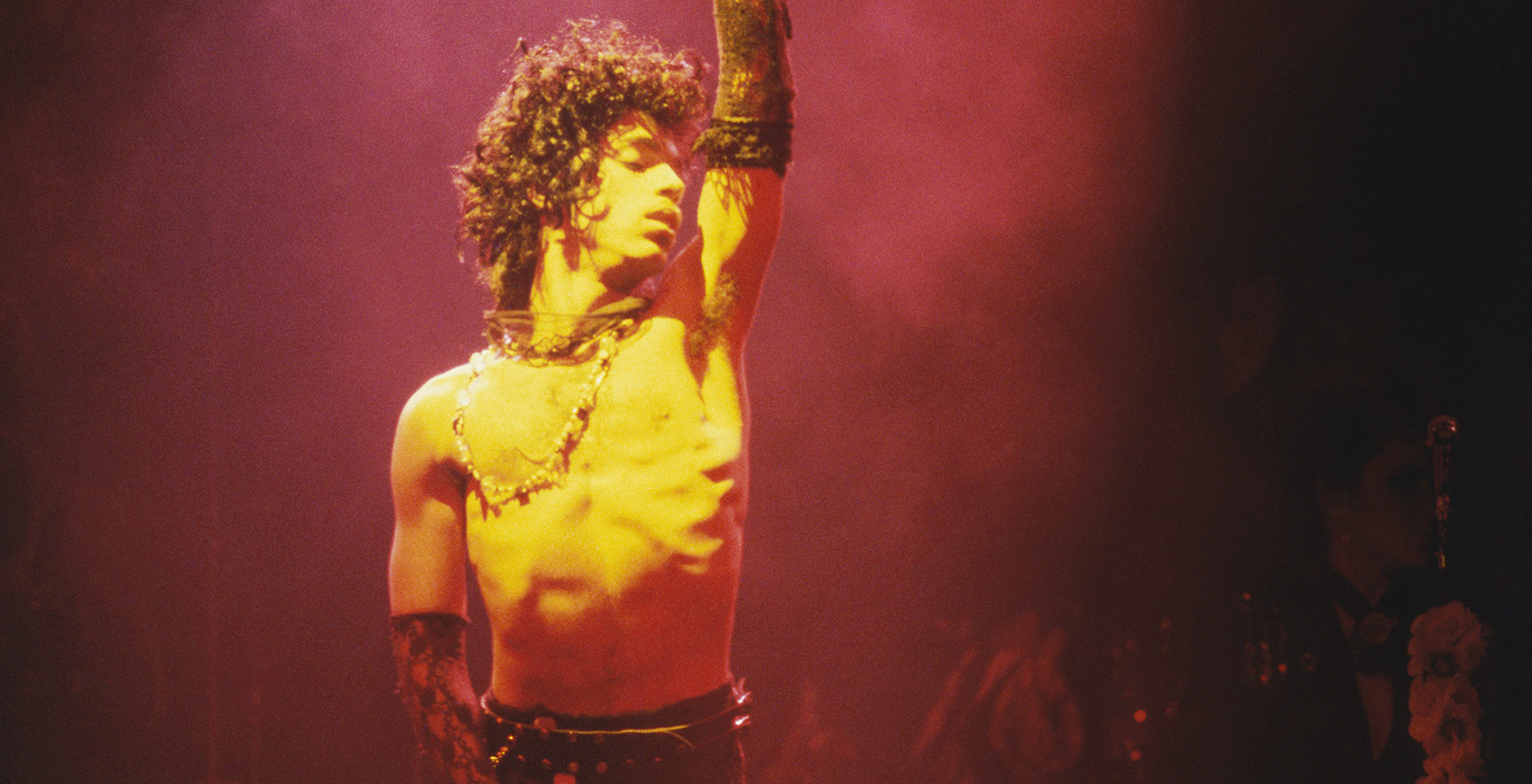

Prince died yesterday, suddenly, at just 57 years old. Hundreds of thousands of words will be written this week about the Purple One and his legacy. Some of those words will be incredibly moving. But none will successfully capture how profoundly, elementally good it has always felt — will always feel — to listen to Prince’s greatest music. Words fail.

More than any other top-tier pop god, Prince defies description, analysis, comprehension — and I’m not primarily talking here about his gender-bending, everything-bending, endlessly fluid public persona. The music itself resists explanation. How do you even begin to describe “Purple Rain” to someone who’s never heard it before? Last summer, when Pitchfork ranked it as the best song of the 1980s — at the top of a list overflowing with great music writing — they devoted only one vague paragraph to the track itself: “brazen,” “wistful,” “dulcet,” “indomitable,” “sweltering.” The other two paragraphs of the write-up focus on its recording and its cultural importance, the kind of stuff our lowly human brains are capable of processing. “Purple Rain” is literally too good for words.

He never toned down the dirty talk. Never traded in pop pleasures for artsy importance. Never stopped dancing.

If that sounds like hyperbole, go back to the tapes. Peak Prince — Dirty Mind, 1999, Purple Rain, Sign o’ the Times — is as good as pop music ever got. It’s also some of the least self-important, most joyful music to ever garner universal acclaim from critics. One of my favorite things about Prince’s legendary run in the ’80s is how he came to be regarded as a “serious” artist without doing any of the things “serious” artists are supposed to. He never toned down the dirty talk. Never traded in pop pleasures for artsy importance. Never stopped dancing.

Instead, he became one of the greats by just being consistently, undeniably, peerlessly great—a virtuoso who chose to use his gifts to please as many people as possible. Prince would spend much of his later years following his muse down weird and sometimes difficult paths, sure, but for more than a decade his music seemed to skip effortlessly from one blissful guitar solo and/or synth blast to the next. And this is why it’s so hard to talk about: How do you elaborate on what feeling good feels like? How do you dissect the urge to dance? Why would you want to?

Genius is rarely so generous, so fun.

On celebrity-grief Twitter yesterday afternoon, many noted that the unexpected losses of Prince and kindred spirit David Bowie just three months apart are proof that we live in a cruel and mysterious universe. I don’t disagree, but losing Prince feels different from losing Bowie, somehow more communal. Millions of people around the world loved Bowie, but we mostly loved him at home, as individuals. His legacy has very little to do with the fact that you might occasionally hear “Heroes” at the bar.

But for more than 30 years, we’ve loved Prince in public: clubs, parties, weddings, the Super Bowl. My sadness over his passing is both tempered and deepened by how many of my favorite memories feature his songs in the background, how many times I’ve personally felt “Kiss” work its magic on a roomful of people. Genius is rarely so generous, so fun. Hugely popular music is almost never so good. Prince opened his most famous album with a spoken reminder that “we are gathered here today to get through this thing called life” — but he gave himself too little credit: When you’re listening to Purple Rain, life isn’t a chore to “get through.” It’s a pleasure.