In 1992, Craig Hodges, a three-point specialist with the championship Chicago Bulls, famously wore a dashiki to the White House and handed President Bush a letter explaining his opposition to the Iraq War and criticizing the United States for its racist policies. The next year, he was out of the league, a “blackballing” he still claims was entirely politically motivated. Hodges’ teammate, Michael Jordan, was the personification of a certain kind of apolitical player: the consummate pitchman who pushes all remotely controversial opinions aside in favour of encouraging more people to drink Gatorade. In 1990, Jordan was asked to support Harvey Gannt, a black democrat running against the notorious race-baiter Jesse Helms. Jordan’s response was typical of the age: “Republicans buy sneakers, too.”

If Jordan was emblematic of the apolitical ’90s, his successor on the court, Lebron James, has become the model for a certain kind of activist athlete. In 2012, James convinced his Miami Heat teammates to pose, heads bowed, wearing hoodies in protest against the shooting of the teenager Trayvon Martin. It was a small gesture that only seemed startling because of the rarity of a millionaire athlete making a political stand. His famous letter, in which he announced he was going home to Cleveland, reads more like a politician’s promise to revitalize rustbelt Ohio than a discussion about free-agency.

James is part of a growing number of athletes determined to use their enormous platform to push political causes, if not candidates. In 2010, the Phoenix Suns played in jerseys that read “Los Suns,” a protest against Arizona’s new anti-immigration law. Last year, members of the St. Louis Rams entered the field with their hands up — a reference to the shooting of Michael Brown in nearby Ferguson. Multiple NBA players have worn T-shirts with the phrase “I can’t breath,” the last words Eric Garner said as the NYPD put him in a chokehold.

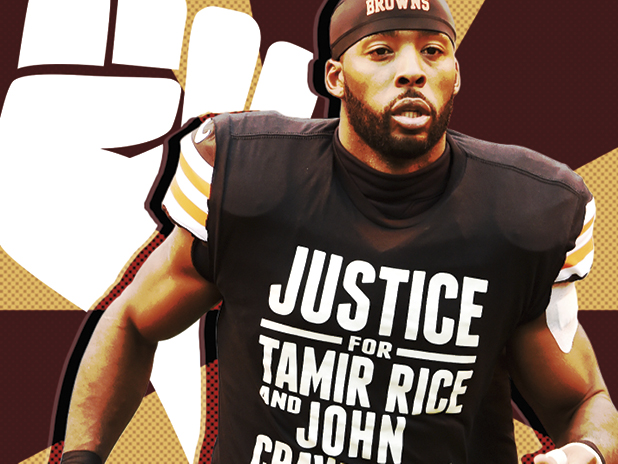

Last year, Cleveland Browns receiver Andrew Hawkins wore a T-shirt in pre-game warm-ups that read “Justice for Tamir Rice and John Crawford.” Rice is the 12-year-old Cleveland kid who was killed by police while playing with an air rifle. Crawford is the 22-year-old shot to death in a Walmart store while holding a toy BB gun. Hawkins’ protest immediately brought a harsh response by local police. “It’s pretty pathetic when athletes think they know the law,” said Cleveland police union president Jeff Follmer. “They should stick to what they know best on the field.”

The next day Hawkins held a press conference. In the past, when a player attacked something as sacrosanct as the military or the police, the backlash would come quickly and he would be chastened by a team eager to avoid controversy. When Hawkins appeared, however, he was unapologetic. He talked about justice. He got choked up, talking about how what happened to Tamir Rice could happen to his two-year-old son. “If I was to run away from what I felt in my soul was the right thing to do, that would make me a coward and I couldn’t live with that,” Hawkins told the press. “A call for justice shouldn’t warrant an apology.”

For politicians, the appeal of sports has always been the access to a huge, non-partisan crowd. It’s a way to reach people en mass, away from tricky questions of governance or the fractious debates that erupt during an election season. Increasingly, though, for athletes who care about particular causes, stadiums and arenas aren’t places where politics are ignored, but places where a message can be amplified. The world is a messy place, full of complications and injustices. Sports can be a discrete bubble away from of all of that or they can — in tiny, incremental ways, one T-shirt at a time — try to make things a little tidier.