How Is Our Obsession With True Crime Affecting Real Justice?

Unless you’re hoping to bury it in the pine-scented deluge of holiday specials, December 18 is not usually the best time to release a challenging new TV series. But the suits at Netflix knew exactly what they were up to when they decided to unleash Making a Murderer right at the start of last year’s Christmas break.

If you, somehow, haven’t heard about it, the docuseries tells the story of Steven Avery, a Wisconsin man who served 18 years for a crime he didn’t commit, was exonerated by DNA evidence, and soon thereafter, was charged, tried and — spoiler alert! — convicted for an unrelated murder. The show’s creators edited down more than 700 hours of raw footage into a comparatively trim 10 episodes, peppered with just enough police bungling and sketchy forensic evidence to drive viewers mad with uncertainty — and into the waiting arms of social media, which was more than happy to consume every free minute of their holidays.

Within days, Making a Murderer lit up Reddit, Facebook and the whole online content industry like a half-ton bomb. One defence attorney became Tumblr’s newest normcore heartthrob. Another received a barrage of hate mail and threatening phone calls (“I hope you die of cancer,” one vigilante told the leukemia survivor). Tourists began showing up on the Avery family car lot to take selfies. Hundreds of thousands of outraged viewers signed a petition demanding President Obama pardon Avery (despite it being constitutionally impossible). And, of course, a legion of laptop detectives offered breathless, ever-wilder theories of what really happened.

Welcome to the new wave of true crime.

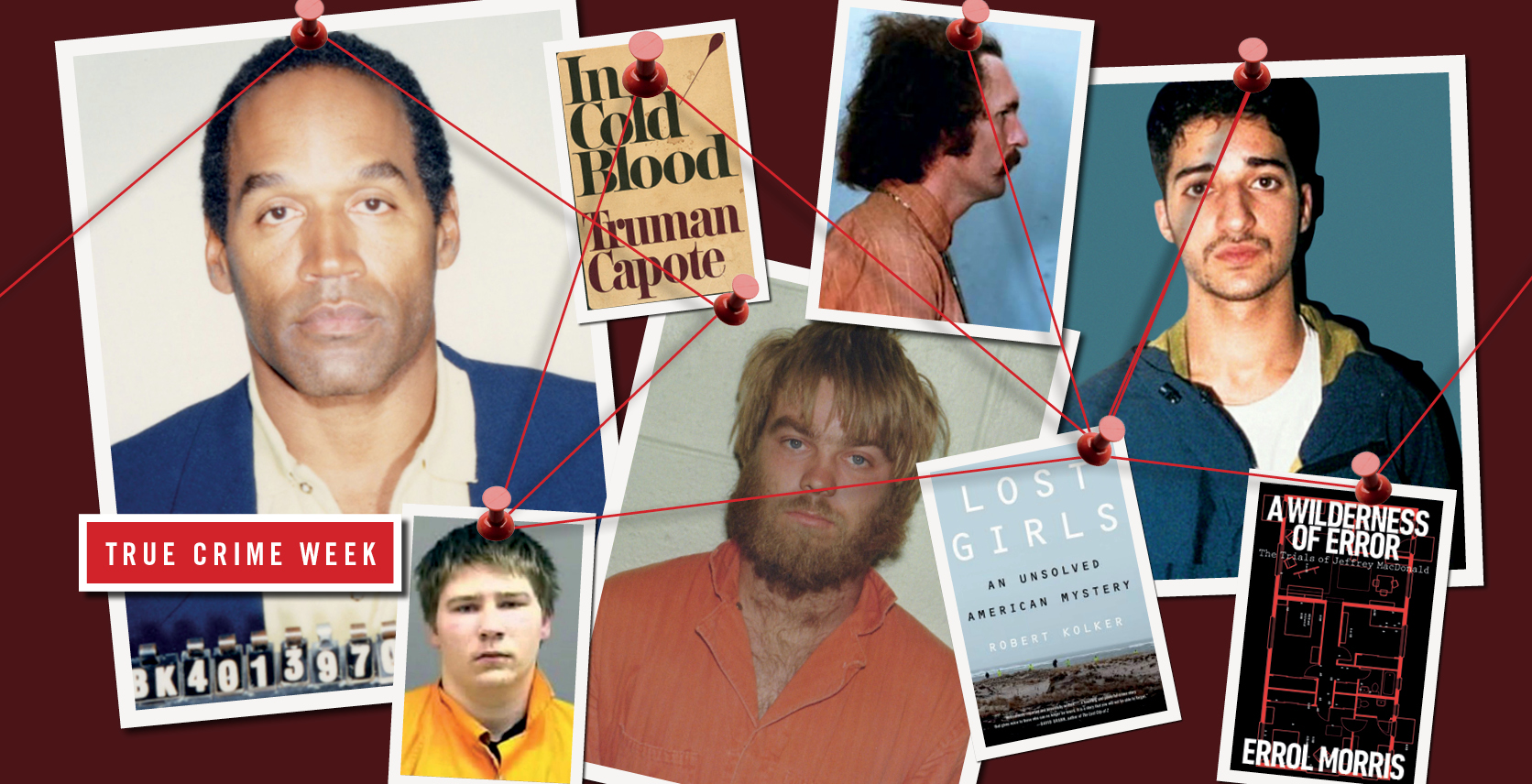

People have always been fascinated with sordid tales of crime and punishment (see: Genesis 34, The Rape of Dinah), and since the dawn of popular literature, publishers have been eager to oblige them. (Even Abraham Lincoln tried his hand in his younger days, with mixed results.) But where a previous generation of true crime stories — Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, say, which just turned 50 — contented itself with pouring over gory details and speculating about a killer’s motives and psychology, this new wave takes its cues from a very contemporary skepticism about the criminal justice system.

Even as crime rates in the US and Canada reach historic lows, mistrust of the courts is pervasive on both sides of the border. You see it in the fiery protests and the weary resignation that accompany the grim parade of unarmed black men and women killed by police officers. You see it in the long campaign for action on the issue of missing and murdered Aboriginal women, in the face of seeming indifference from authorities. You see it in the legion of women who doubt the ability — or even willingness — of the system to prosecute crimes of harassment and sexual violence. And you see it in the attempts to walk back the overreaches of the war on drugs, and the swelling prison populations left in its wake.

Then there’s the steady stream of revelations about basic flaws in what you might call the CSI worldview. Just last April, in a startling admission, the FBI reported that its elite microscopic hair analysis unit had made errors in 96 per cent of its cases, errors that helped sentence 33 people to death (of course some of those people may still have been guilty). Bite mark matching, polygraphs, voice printing, arson investigation, blood splatter analysis… after close scrutiny, they’ve all come out looking less like science than like high-tech tasseography.

Nowhere is this skepticism more evident than in stories about potentially innocent people ending up behind bars. Call it exoneration-core. In Serial, the breakout 2014 podcast, we followed WBEZ’s intrepid Sarah Koenig on her painstaking re-investigation of the 1999 murder of a popular high schooler named Hae Min Lee and the subsequent conviction of her ex-boyfriend Adnan Syed. Twelve episodes later — 12 episodes of shifting testimony, uncovered alibis, and perfectly calibrated narrative hooks — millions of listeners walked away convinced of Syed’s innocence (at press time, a Baltimore Circuit Court Judge was set to rule on a retrial). Koenig, famously, was more equivocal: “As a juror, I vote to acquit… but… If you ask me to swear that Adnan Syed is innocent, I couldn’t do it. I nurse doubt.”

That same doubt is central to the appeal of Making a Murderer, with half the Internet rallying for Steven Avery’s acquittal and the other half crying foul over inculpatory evidence that the filmmakers supposedly withheld. Amplify that doubt through social media’s sounding boards and echo chambers, and you have the making of a contemporary true crime hit. And if you think Making a Murderer was big, just wait until this June, when ESPN releases its highly anticipated five-part documentary series, O.J.: Made in America.

But isn’t there something unseemly in all this? In using the techniques of what Koenig has referred to as “escapist entertainment” — cliffhangers, misdirection, Game of Thrones-style theme music — to tell stories about real victims and their grieving families? And in inciting all the binge watching, meme-ing, online crushes, and spoiler dodging that usually accompany the latest prestige cable drama?

During the first season of Serial, the brother of Hae Min Lee ventured onto Reddit to take some of the show’s fans

to task. “To you listeners, it’s another murder mystery, crime drama, another episode of CSI,” he wrote. “You weren’t there to see your mom crying every night, having a heart attack when she got the news that the body was found, and going to court almost every day for a year seeing your mom weeping, crying, and fainting…. I pray that you don’t have to go through what we went through and have your story blasted to 5 million listeners.”

Still, there’s an upside to all this armchair sleuthing, according to Russell Silverstein, co-president of the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted in Toronto. “I think it’s great!” Silverstein told me. “Nobody who hasn’t sat through an entire trial from start to finish ever can say that he or she really understands the entire case. There’s no such thing as being overeducated when it comes to stuff like this.” And the more people become familiar with the litany of ways that evidence can be abused — coerced confessions, faulty eyewitness accounts, junk science — the harder it gets to convict an innocent person.

•••

AS COMPELLING as exoneration-core may be, there’s a whole world of thoughtful, challenging true crime just beyond its borders. Take A Wilderness of Error, the magisterial 2012 book from filmmaker Errol Morris, which goes deep into the notorious trials of Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald, the “green beret killer,” and offers a profound meditation on the nature of doubt, justice, and proof. (Morris, whose groundbreaking 1988 film The Thin Blue Line helped free an innocent man from a life sentence, is working on a new true crime series for Netflix — get excited.)

Or Robert Kolker’s Lost Girls, a deeply humanizing portrait of five young women all probably killed by the same Long Island serial killer, and a primer on the economics and sociology of buying and selling sex in the digital age.

And my favourite: Criminal, a podcast whose host, Phoebe Judge, describes it as “fascinated about all the different ways in which crime can touch someone’s life” — from the lurid to the mundane. So alongside the usual serial killers and exonerations is an interview with a woman who used to print counterfeit 50-dollar bills on her inkjet printer, or a story about a cop who had to dive into LA’s primordial La Brea Tar Pits to unearth a piece of evidence. And then there’s the episode “695BGK,” which shifts the lens from true crime’s more typical victims to tell the story of an unarmed black man shot by a police officer.

“Our job is not to say this person is good or bad,” Judge told me. “Our job is to tell the story, and to show what we hope is as complete a picture as possible of these people who have been touched by these events. And that’s what’s fun about true crime: if you do it in a certain way, the listener gets to be the judge.”

For the foreseeable future, whether you like it or not, court is in session.