Inside the Wonka-Like World of La Fabrique du Temps, Louis Vuitton’s High Watchmaking Facility

From the top floor of La Fabrique du Temps, Louis Vuitton’s watchmaking facility in Geneva, you can see clear across the Swiss border and all the way to France. This is true of many places in the watchmaking capital of the world, but it’s especially notable here. Almost visible across the verdant line of trees and grass, a little further north and a little further west — or about an hour’s car ride away — is Anchay, the town where Louis Vuitton himself was born.

Vuitton didn’t stay long in this part of the world. At 13 years old, so the story goes, he packed up his belongings and set out — on foot — along the nearly 500-kilometre journey to Paris. More than 150 years later, though, the eponymous company he founded returned to the region of his birth for much the same reason he once left it: the pursuit of excellence, and perhaps an entirely new legacy.

Of course, a legacy in high watchmaking is not an easy thing to forge from scratch. There’s no shortage of top-tier watchmakers in Geneva, and many of them have been perfecting their products for hundreds of years, since long before Louis Vuitton (the man) was even born. While Louis Vuitton (the brand) has long been known for trunks, travel accessories, and fashion, it didn’t release its first timepiece until 2002. And it didn’t have a dedicated facility — with all the requisite knowledge, experience, and inherited watchmaking wisdom of a seasoned team of craftsmen — until it took over La Fabrique du Temps less than a decade ago. And that’s when things got interesting. Inside this plain grey building on the outskirts of Geneva, Louis Vuitton has quietly been developing a very different kind of watchmaking institution — and like the watches it produces, its inner workings are fascinating to behold up close.

•••

The centrepiece of La Fabrique du Temps is a spiral staircase linking the upper floors — mostly offices and communal space — with the secretive watchmaking facilities down below. Built to resemble a watch spring, the staircase took two attempts to construct. The first time, the complicated cantilever didn’t quite take, and the whole thing came crashing down; the second time, it wasn’t just sturdy — it revealed itself almost as sculpture. “It’s symbolic of what we do here,” says Hamdi Chatti, vice president of watches and jewellery at Louis Vuitton. “We take risks, but we always strive for perfection.”

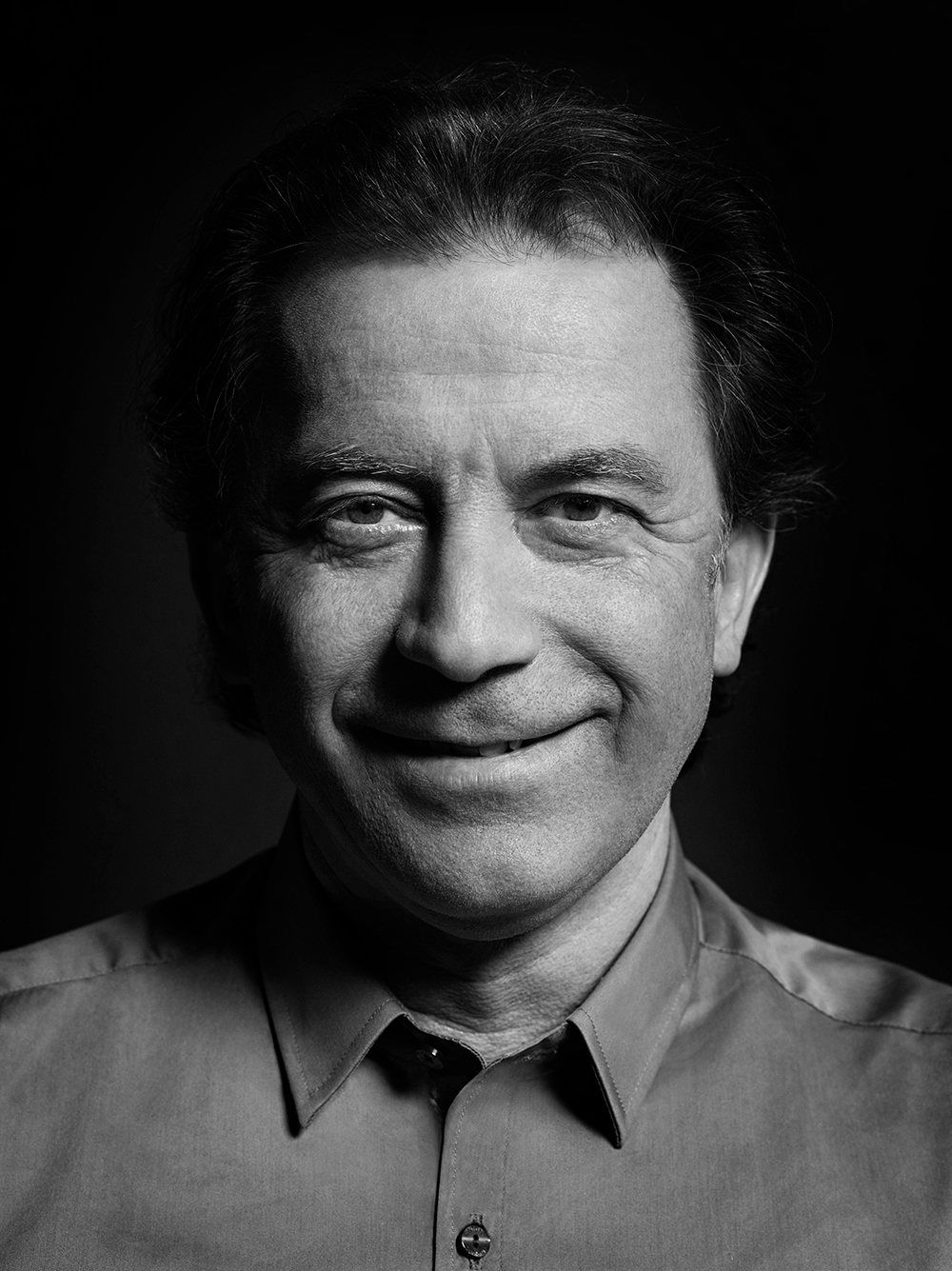

Chatti knows what he’s talking about. With an engineering background and a master’s degree in horology, Chatti has worked with some of the top watchmakers in the world, including Piaget, Montblanc, and Harry Winston. When he arrived at Louis Vuitton in 2009, one of his first orders of business was to solidify the brand’s watchmaking division. That meant getting in touch with master watchmaker Michel Navas — and convincing him that this position was unlike anything else he’d be offered in Geneva.

La Fabrique du Temps is Navas’s own invention, conceived alongside his partner Enrico Barbasini. Louis Vuitton only acquired the operation in 2011, and this new, consolidated building opened in 2014. Before then, Navas had built a reputation as a master craftsman — and a kind of watchmaking idealist. Born in Spain to a watchmaker father, Navas landed in Geneva with impeccable skill and something to prove. He spent years working for big Swiss brands before he partnered with Barbasini and they headed out on their own.

“I come from big brands,” says Navas. “I am the old school. With the designers of Louis Vuitton, together, we have the utmost respect for high watchmaking, the legacy of our grandfathers, but we look forward with new technology, new designs — the modern touch of Louis Vuitton. That’s why we are different.”

That risk-taking mentality suits Navas just fine. His first project under the LV umbrella was the Escale Worldtime, a wildly colourful watch that tells time with a complex series of hand-painted cubes. It remains one of the brand’s most iconic timepieces, although not necessarily Navas’s favourite. That, he would reveal if pressed, might be the Tambour Minute Repeater, which deftly indicates a second time zone using chimes rather than a more traditional second dial. “Nobody does that,” says Navas. “It was a challenge, but we are very different for that.”

That adventurous spirit is what sets Louis Vuitton’s watchmaking apart, and is one of the reasons the brand was able to bring Navas and Barbasini into the fold in the first place. “They were surprised, actually,” says Chatti, “because in Vuitton there is one ingredient — it is not a secret; it is well-known, but people do not believe it’s true: you always have a wild card in this company. If it’s creative, if you have the craft, you can do it. And they actually have that wild card. If they have a good idea, they can do it.”

•••

There is another benefit to being located in Geneva alongside Swiss rivals: eligibility for the Poinçon de Genève. Established in 1886 under the laws of the City and Canton of Geneva, the Seal (as it translates in English) is an independent body that governs the quality of watch movements. For many, it is considered the industry’s highest honour — a testament to a brand’s dedication to careful, precise, and innovative watchmaking. This was always the goal when La Fabrique du Temps was established. And it’s one they have since achieved twice: first with the Flying Tourbillon, a transparent watch with a tourbillon regulator and a calibre that looks almost suspended in midair, and then again last year with the Tambour Moon Tourbillon Volant, a skeletal, diamond-encrusted reimagining of the original Tambour.

“The Geneva Seal was sort of a little joke between us,” says Chatti. “I like traditional watchmaking. But I think it’s boring for Vuitton. I mean, we don’t have 150 years of history in watches. So the whole conversation was not about whether we should have the Geneva Seal or no, but whether the Geneva Seal will allow us to design a contemporary design that stands for Louis Vuitton.” He pauses. “I think it worked out pretty well. It’s very transparent. It’s very modern. It’s totally different.”

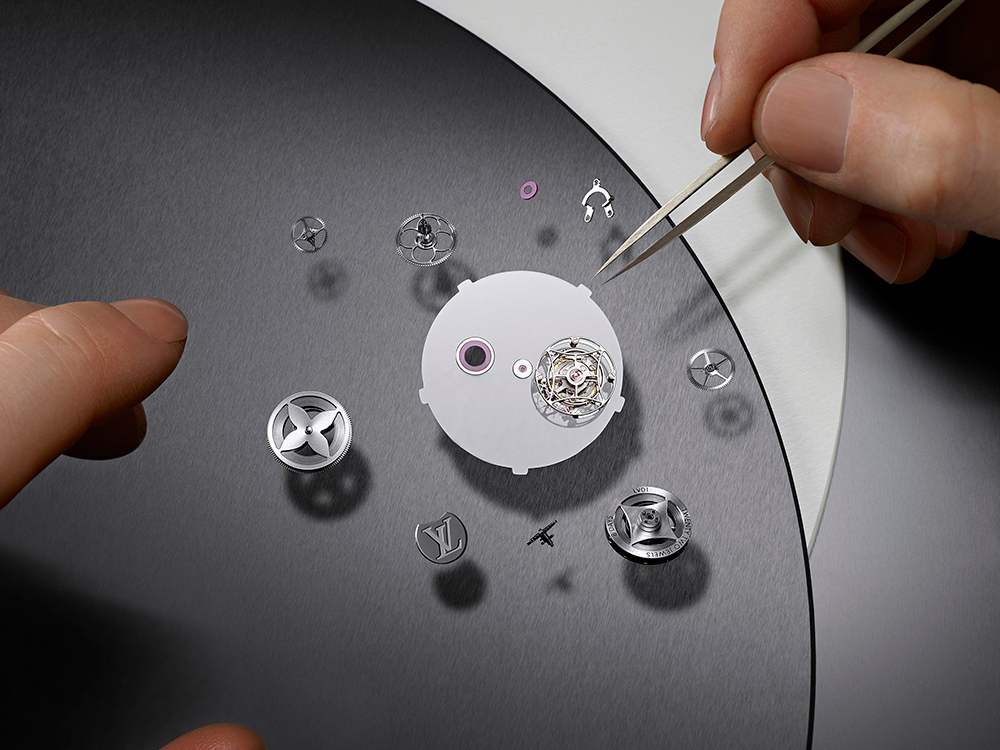

Evidence of the skill required to earn the Seal is everywhere in the facility. Deep in the bowels of the building, through a series of hallways and locked oak doors, the watchmakers labour away at these special timepieces with great concentration and pride. In the brightly lit main studio, three rows of chest-high desks accommodate these exceptionally skilled craftspeople. Today there are five — there are 12 in total at the facility, eight of whom are dial makers — each working on a single watch that may take four months of constant, precise work to complete. Navas is currently searching for more people, but

it’s not easy to find the right combination of practised skill and innovative spirit. “Everyone comes from these big brands, and they are used to that style,” he says. “It’s good here to be imaginative. You have to be different.”

Maybe that’s why Navas and Barbasini have their own desks nearby, both still prepared to take on the work of assembling a complicated mechanism. Despite their years of experience, harried travel schedules and frequent sales calls, they continue to practise their craft; their hands touch nearly everything here. They oversee it all, from the initial design to the fine, computer-assisted sketching to the resin modelling to the metal cutting and tinting (or, in the case of the Worldtime, the excruciating hand-painting), and through to the final assembly.

It’s a long process, but Navas is used to it. “For the watchmaker, we want to know the baby very quickly, but we have to first design, we have to order the components, we have to make the components, and we have to check and assemble and make the prototypes… It takes years.”

The results, though, are worth it. Especially when they’re a little unusual. For proof, take a look at Navas’s right wrist. Opposite the mechanical watch he wears proudly on his left is a black Tambour Horizon, the brand’s first foray into smart watches. It’s a departure for Navas and his team at La Fabrique du Temps. They helped design its overall look and feel: it’s housed in a round metal case evocative of the original Tambour, and its visual display is distinctly Louis Vuitton. But inside, of course, there are no screws or dials. Instead, they relinquished control of the interior to a team in Silicon Valley, which designed and assembled an interface that could match Chatti and Navas’s strict aesthetic instructions.

“I think what makes the watch different is that, first of all, it’s beautiful,” says Chatti. “It’s a nice object, and you like to wear it. And nobody wears it just for the technology.”

Navas agrees. And in fact, he hopes that the success of the Horizon (which was introduced in June last year and sold out its first run long before Christmas) indicates a new golden age for watches. “Today, young people aren’t used to putting something on their wrist,” he says. “If it’s a way to put something on the wrist, I think they might start with a smart watch, but they finish with a very nice mechanical watch. And we have two wrists. You can wear both!”

Back upstairs, over a Nespresso and Swiss chocolate in the cafeteria, Navas and Chatti can’t help talking about the future. About all the unorthodox directions they’re moving in. “It starts with a simple idea,” says Chatti. “Like a minute repeater. And then we ask, ‘How do we make it Louis Vuitton?’ A second time zone you can’t see, only hear? Well that’s just crazy enough to get everybody excited.”