Why Netflix’s Documentary Obsession Isn’t Exactly Good for Documentaries

One Saturday afternoon this spring, on the first warm day after what felt like a century of winter, a few hundred Torontonians willingly filed into the dark, sticky-floored bowels of the Scotiabank theatre to watch a documentary about a film that was never made.

The doc, Shirkers, is a mystery movie and a restoration project. Twenty-five years ago, 18-year-old Sandi Tan and her friends were punk teens in Singapore obsessed with Jim Jarmusch movies and the Velvet Underground. Determined to make their own arthouse picture, the teens teamed up with an older American, Georges Cardona — a cold-eyed, enigmatic figure who introduced the girls to French new-wave cinema and claimed to have been the inspiration for James Spader’s character in Sex, Lies, and Videotape. Together, they shot a wild, absurdist road movie about a female murderer on the run. After the shoot, however, Cardona vanished without a trace, taking the film canisters with him. Twenty-five years later, Tan recovered the footage. Her documentary tries to puzzle out Cardona’s motivations while piecing together the story of a film that never existed.

Shirkers played at Hot Docs, the Toronto film festival. The screening began with a video paying tribute to the many filmmakers who were “documenting our times.” When it ended, the audience broke into applause before wandering out into the lobby to share industry gossip. The screening — a communal experience in a crowd of documentary lovers — was invigorating. It was also one of the last times the movie will be seen on the big screen. Earlier this year, the movie was bought by Netflix, part of the company’s voracious plans to take over the once sleepy documentary industry.

•••

Netflix entered the documentary business a few years ago with all the mysteriousness and disarming confidence of Georges Cardona approaching a group of teens. Representatives from the streaming company simply began showing up at the forums where filmmakers traditionally gather to pitch their ideas to penny-pinching public broadcasters from around the world.

“At the beginning, people would whisper, ‘I hear that there’s someone from Netflix here,’” remembers Sarah Spring, a documentary film producer in Montreal. The streaming people were anonymous and enigmatic. And they had deep pockets, bypassing the complicated web of international partnerships that usually fund a production and instead snatching up docs whole, paying for their global rights. For earnest documentarians used to cobbling together a budget, Netflix felt God-like in its power — terrifying and awe-inspiring. To have your film chosen by the company felt like a miracle.

Spring says Netflix is interested in two kinds of docs: super-traditional, four-act movies that cover a hot-button topic, and swing-for-the-fences experiments like Making a Murderer. One documentary sales agent told IndieWire that all the buzz around non-fiction had put pressure on filmmakers to pursue “character-driven narratives or very high concept [stories]”. A traditional “issues documentary” didn’t have a chance against something flashier.

“By placing the documentary in the same queue as the latest Adam Sandler disaster, Netflix transforms the genre. Freed from the framing of a film festival, they lose their halo of seriousness and prestige.”

In an interview with the New York Times last year, Lisa Nishimura, the vice president for original documentary and comedy programming at Netflix, explained that the streaming service was simply exploiting a hole in the market. Documentaries were popular, she said, but that popularity wasn’t being reflected in the box office. “Television ratings exist because of ads, which we’re free of, and box office has become so reliant on Friday night returns that it’s warped perceptions of what audiences want,” Nishimura told the Times.

Today, scrolling through the company’s documentary offerings online reveals a mountain of content. Netflix has behind-the-scenes music docs like What Happened, Miss Simone? and Gaga: Five Foot Two and true crime docs that cover the hits, from JonBenet Ramsay to Amanda Knox. They’ve got ordinary biopics of extraordinary people, like Joan Didion: The Centre Will Not Hold, and irritating biopics of awful people, like Get Me Roger Stone.

The documentaries benefit from the same Netflix bump that their mediocre scripted shows enjoy. The convenience is so high, and the barrier to entrance is so low, why not try out a documentary about Adderrall addiction? Click your way far enough and you quickly find the 9/11 truther Zeitgeist trilogy. You get Patient Seventeen, a doc about a surgeon who removes implants embedded by aliens, and a host of other conspiracy theory movies that promise to tell you who built the Egyptian pyramids and how the New World Order is enslaving mankind — productions that benefit from the atmosphere of seriousness created by the prestigious docs next to them in the queue.

The reason Netflix doesn’t have a coherent slate of docs, of course, is because they’re not trying to be one unique solar system in a universe of content; they want to be the universe itself, every star in the firmament a Netflix Original, flickering beguilingly, waiting for you to click. Whether you choose Ava DuVernay’s Oscar-nominated documentary about mass incarceration or Aliens on the Moon: The Truth Exposed doesn’t much matter.

•••

On a weekday evening around the same time I saw Shirkers in theatres, I finished off the Netflix series Wild Wild Country from the comfort of my couch. The six-part series follows the Rajneeshi sex cult and their increasingly out-of-control battle with the locals in 1980s rural Oregon. The series has fascinating characters, a momentum-building indie rock soundtrack, and a twist in the final minutes of each episode, the now familiar hallmark of a Netflix show in the binge-watch era. It’s too credulous as a piece of journalism, ignoring some of the worst acts of the cult. But as entertainment — a show I watched while buzzed from a couple of tall cans, eating an enormous bowl of expensive grapes and scrolling through Twitter on my phone — it’s a success.

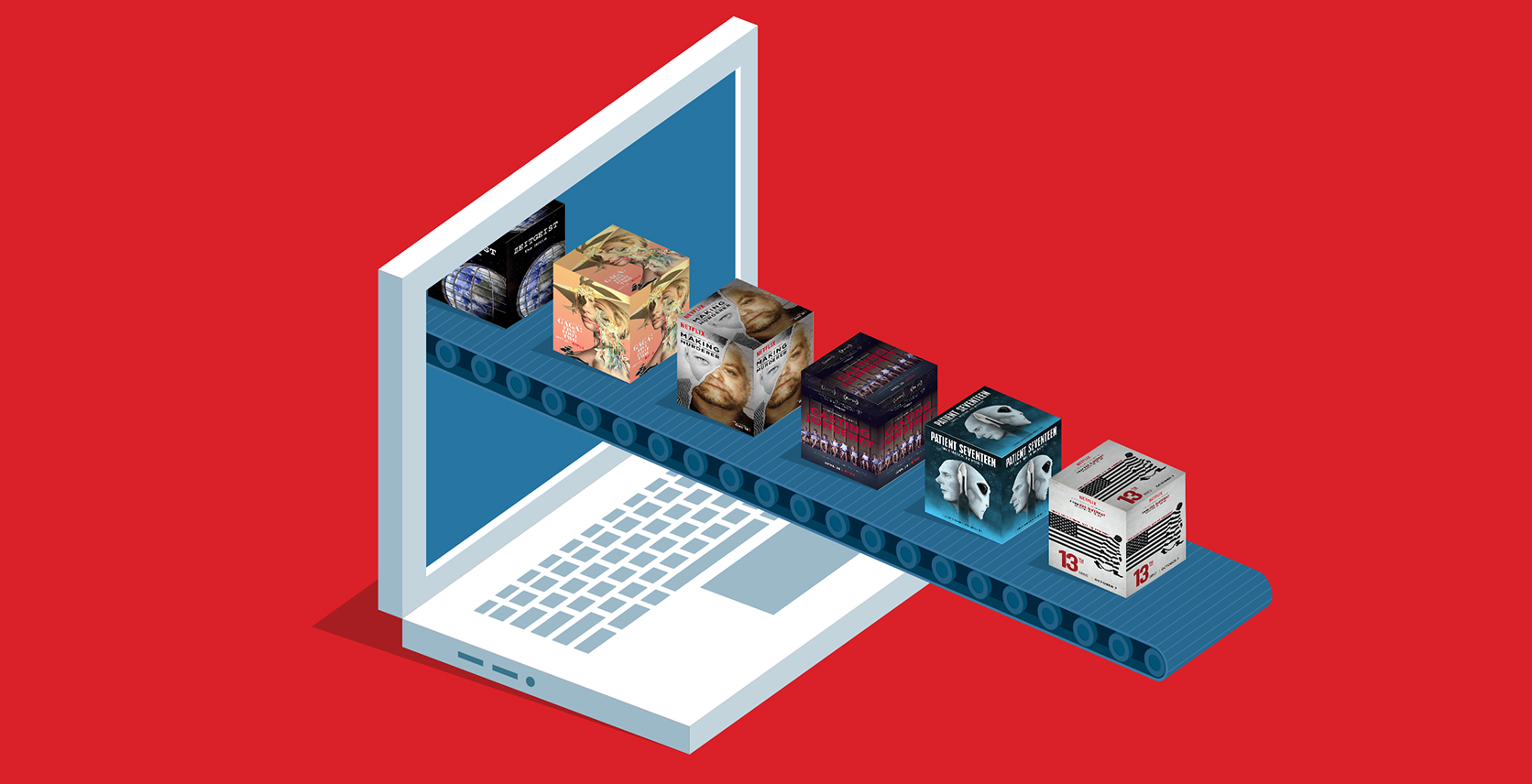

And that’s the small but profound thing that Netflix does. By taking the documentary and placing it in the same algorithmic queue as the latest Adam Sandler disaster or the new season of The Santa Clarita Diet, the service transforms the genre. Freed from the framing of a PBS special presentation or a film festival, documentaries lose the halo of seriousness and prestige that so often hovers over them. They are not imbued with the holy mission of documenting our times. They’re simply more content for the mill, judged by the same standard (“Is this sufficiently interesting to fill the two hours between when I put my awful children to bed and when I pass out from exhaustion?”) as everything else on the homepage. And if Wild Wild Country, like so many Netflix shows, is kind of bloated and not as good as you’d hoped, the convenience of the experience more than makes up for what’s lacking. Besides, there’ll be a new show next week.

At its Hot Docs screening, Shirkers felt like a tribute to film. Stuck in notoriously uptight Singapore, Tan had to convince her cousin in Florida to tape a copy of Blue Velvet and send her the VHS. Her documentary is about passionate teenagers going to great lengths to find the art that speaks to them. It’s about a filmmaker recovering her lost project, lovingly trying to restore the movie and struggling to bring it to an audience. It will be available to Netflix subscribers around the world later this year, fit snugly between episodes of Queer Eye and Lost in Space — yet another morsel of content in the gargantuan streaming machine.