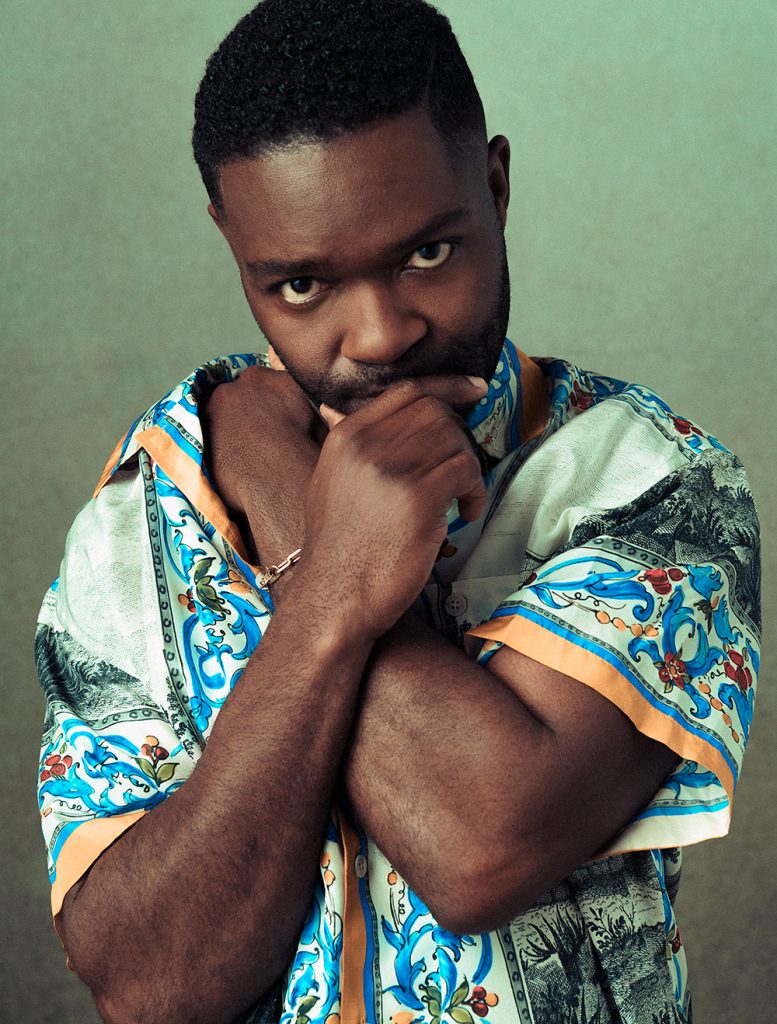

The Reintroduction of David Oyelowo

David Oyelowo does not have an Oscar.

He wants this to be clear. When the British-American actor, producer, and director appears on late-night television, or is interviewed on the red carpet, or speaks before a crowd, this is how they often introduce him: “Oscar-winner David Oyelowo.” It’s embarrassing. It would be one thing if he had lost an Oscar. But he wasn’t even nominated. “I’ve stopped correcting people,” he confesses. “It’s too awkward to stop them and say no, sorry.” Though I suspect there is another explanation. Oyelowo may sense that, if people continue to think of him as an Oscar winner, eventually it may come true. So let’s amend that. David Oyelowo does not have an Oscar — yet.

The misconception is revealing. It’s a testament to the extent of the acclaim Oyelowo received five years ago, when it seemed as if the world were united in admiration for his performance as the immortal Martin Luther King Jr., in Ava DuVernay’s civil rights drama Selma. Few actors have been exalted with such enthusiasm by critics and international awards bodies. And few actors, when it was time for that year’s Academy Awards, have been so flagrantly snubbed. It seemed all anyone could talk about. And Oyelowo soon came to resent that pernicious little word. “I’ll be honest with you,” he says. “It was painful to put your heart and soul into something, for it to be received so well, and yet the word that recurs everywhere you go is ‘you were snubbed.’”

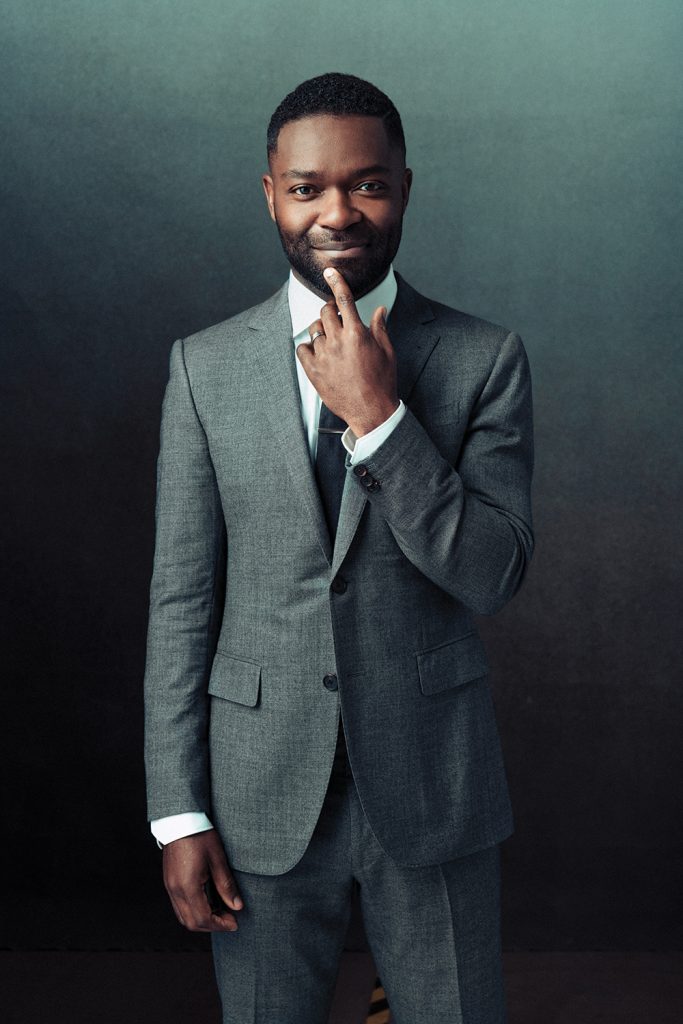

SHIRT (PRICE UPON REQUEST) BY SALVATORE FERRAGAMO; PANTS ($465) BY ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA; SHOES (PRICE UPON REQUEST) BY SALVATORE FERRAGAMO; WATCH ($7,700) BY HUBLOT.

Oyelowo might not have appreciated “all that negativity around something positive,” but such impressions have unmistakable advantages. “It did what it was destined to do and more,” he concedes. “It afforded me most of the opportunities I’ve had.” In the half-decade since Selma and his missing nomination, Oyelowo has made good on his reputation as a man who merited the industry’s top prize. Consider his most recent projects: a critically acclaimed adaptation of Les Misérables for BBC, in which he plays Inspector Javert; the fantasy drama Come Away, in which he stars opposite Angelina Jolie; the sci-fi horror film Revive, which he also produced; and The Water Man, a Disney period drama starring him, produced by him, and directed by him. And that’s just this spring.

In 1998, while studying at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, Oyelowo landed his first two roles back to back — bit parts in a pair of obscure English TV shows, Brothers and Sisters and Maisie Raine. “I think I was a bit of a ne’er-do-well young man on the wrong side of the law in one of them. Fairly stereotypical, I would say,” he remembers now. Still, it was something, and at the time he was justifiably thrilled. He was 22. “I was calling everyone to tune in. I come from a family where being an actor just was not celebrated or applauded. So it was a huge source of excitement for me — and a huge source of chagrin for my fellow classmates.”

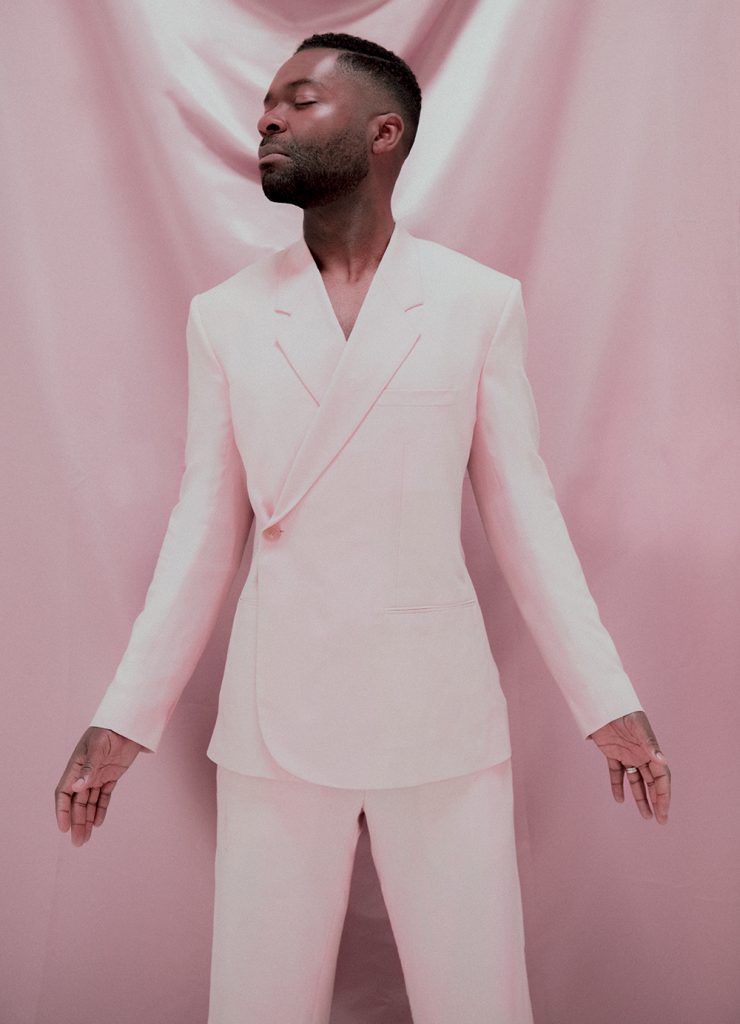

SWEATER ($1 ,225) BY ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA; PANTS ($1 ,100) BY HERMÈS; SHOES ($525) BY BALLY; WATCH ($4,450) BY BREITLING.

His first feature film role was in a raunchy sex comedy about aspiring DJs called Dog Eat Dog. “Oh my god,” he groans at the very mention of its title, suppressing bales of laughter. It’s noteworthy mainly for marking the earliest appearance of Ricky Gervais on the silver screen. (“He has one line, and of all things, he plays a bouncer. Have you ever known a less likely bouncer than Ricky Gervais?”) About this inauspicious debut he wishes only to issue a warning: “Do yourself a favour. Do not watch that film.”

But Oyelowo’s real breakthrough wasn’t a performance at all — it was just the suggestion of one. In 2010, on the heels of a Best Director nomination for his work on Precious, Lee Daniels signed on to make a biographical film about Martin Luther King and his marches from Selma to Montgomery. His version of the movie would never happen, but before he dropped out of the project, he enlisted Oyelowo, then a mostly unknown British actor, as its star. “It was a night and day situation,” Oyelowo recalls. “Suddenly the industry kind of went, who? Who’s he casting as Dr. King?”

“We have to keep fighting to world we live in.”

In the days following the announcement, Oyelowo was besieged by calls for meetings and offers for auditions or jobs. Tate Taylor is on line one: he’s heard Oyelowo is playing Dr. King. Does he want to come play a preacher in The Help? 20th Century Fox is on line two: any interest in Planet of the Apes? This accounts for how he seemed to get more plum gigs in 2011 and 2012 than most actors get over entire careers. He appeared opposite Tom Cruise in the action blockbuster Jack Reacher. He starred alongside Zac Efron and Nicole Kidman in the movie Daniels made instead of the MLK biopic, Southern Gothic drama The Paperboy. And he worked on a series of what he calls his “small roles with great directors”: George Lucas (Red Tails), Steven Spielberg (Lincoln), and Christopher Nolan (Interstellar).

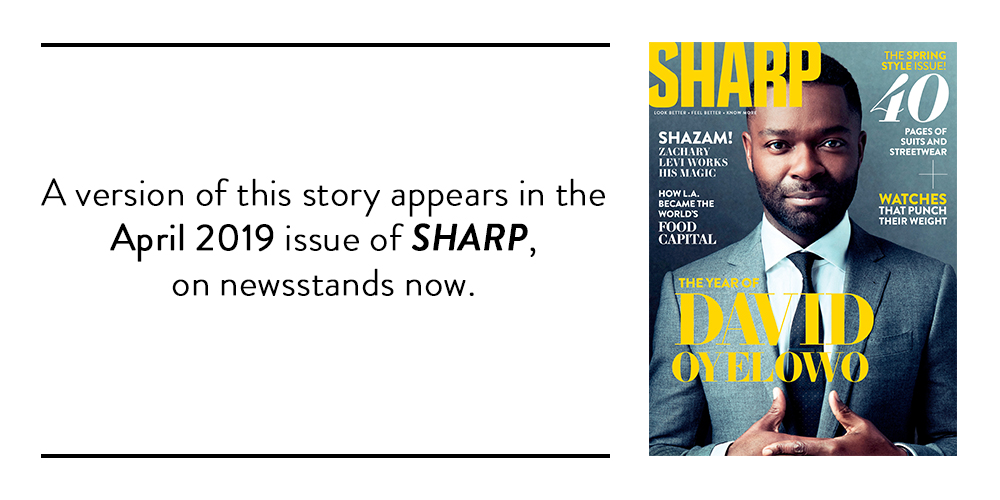

SUIT (PRICE UPON REQUEST) BY CHRISTIAN DIOR.

One evening around this time Oyelowo found himself on a flight to Vancouver. Beside him was a man binge-watching Spooks, an old British spy show that had been off the air for years — and on which Oyelowo had a recurring role. Midway through the flight, the man turned to Oyelowo and realized he was one of the spies he was watching on TV. So he decided to ask his advice about an entertainment-biz matter. “He had been approached to finance a movie,” Oyelowo says. “And he wanted to know if I thought it would be a good idea for him to do it.” Not wanting to offer bad counsel, Oyelowo asked if he could read the screenplay, written by a young filmmaker named Ava DuVernay.

The movie was Middle of Nowhere. Oyelowo liked the script enough to ring DuVernay up later to ask for a part — and as it happened, DuVernay already had Oyelowo in mind. A sensation at Sundance in 2012, Middle of Nowhere fortified Oyelowo’s flourishing stature, and more importantly, marked the beginning of what Oyelowo insists “was one of the most creatively exciting and formative moments” of his career. Meeting DuVernay, he’d found a “creative soulmate.” At this time he was acting in films by some of the most illustrious directors in Hollywood. It was DuVernay who impressed him most of all. Her methods spoke to him, in ways he’d never experienced with other directors; she “got things out of me,” he says, “that I didn’t know were there.” The collaboration on Middle of Nowhere was so fruitful that, when Daniels severed his ties with Selma and the project needed a replacement at the helm, Oyelowo knew exactly who it should be.

SWEATER ($350) BY APC.

His recommendation proved fortuitous. Selma was a staggering hit. Oyelowo is extraordinary in the film: he doesn’t so much play Dr. King as wholly embody him, seeming to exude the man’s abiding decency and unflappable poise. So effusive was the praise for his work that an Oscar seemed a given. And so taken for granted was this assumption that when that year’s Oscar nominations were revealed and Oyelowo and DuVernay were overlooked, moviegoers were shocked.

A grassroots campaign emerged on social media, whose participants lambasted the Academy for their obvious racial bias. This hashtag campaign — #OscarsSoWhite — galvanized an institution notorious for its indifference to minority voices, jolting voters out of bone-deep apathy and effecting real change. It was a more lasting victory for Oyelowo and Selma than if he or the film had simply been honoured with trophies. “This was a film about injustice in voting,” he says looking back at Selma and the protest it inspired. “The fact that it recalibrated how Hollywood votes is a beautiful irony.”

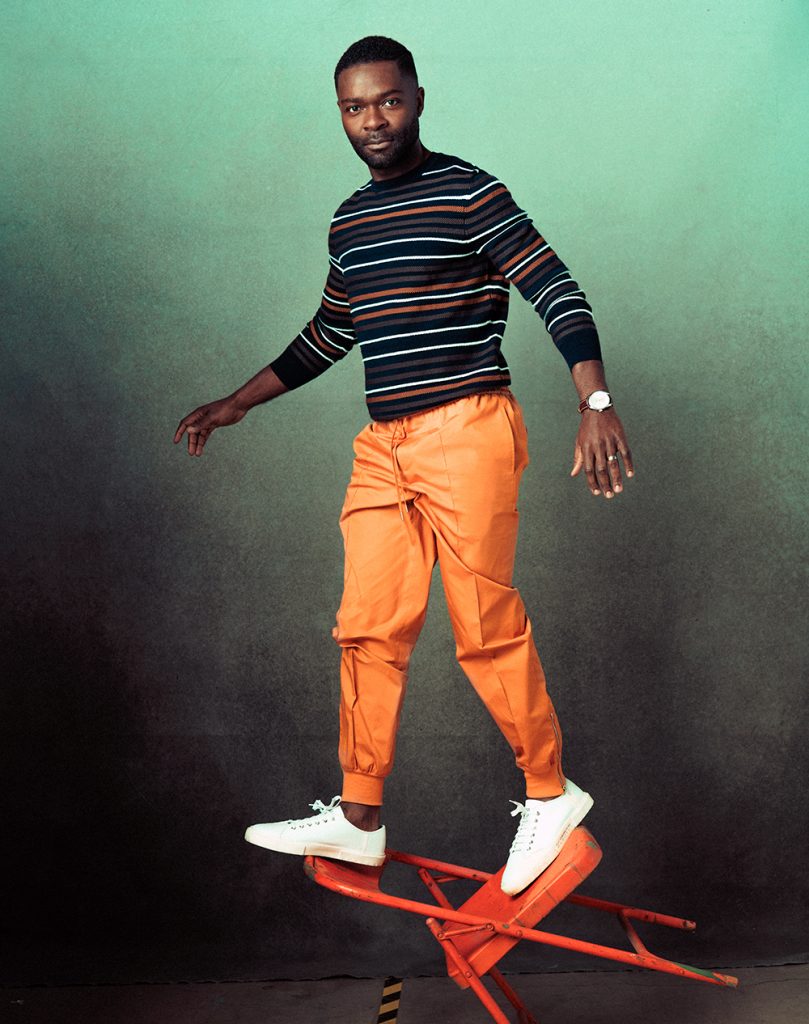

SUIT AND TIE (PRICE UPON REQUEST) BY LOUIS VUITTON; SHIRT (PRICE UPON REQUEST) BY ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA.

Change came swiftly. The Academy inducted leagues of new, diverse members; they encouraged longtime voters, largely old and white, to retire. In the wake of Selma, Moonlight won Best Picture. Get Out and Black Panther were Best Picture nominees. “It really put the Academy’s feet to the fire in terms of representation. It helped change Hollywood, and it’s one of the biggest legacies of the film.” And meanwhile, David Oyelowo has been enjoying the kind of career customarily reserved for men who’ve just been awarded Best Actor.

SWEATER ($2,475) BY HERMÈS.

Of course, if he spends another 40 years acting, Oyelowo will probably still be remembered as the man who played Martin Luther King — a tribute to the calibre of the performance, not his limitations as a performer. Oyelowo has the range for much else besides playing Dr. King. “After Selma, I was offered, and still am offered, a plethora of civil rights stories that basically cover the same terrain,” he says. “Now, as wonderful as it is to know those stories are out there, I don’t think I need to be the guy to tell all of them. I don’t think I need to be the guy to tell any more of them, to be frank.”

His interest going forward is in variety — including, most of all, the kinds of roles he would not have originally been offered. “Some of the best stuff tends to be written with a white male actor in mind,” he says. “Historically, that’s who Hollywood favours — because that’s who the upper echelons of Hollywood is comprised of.” He has overcome the prejudice before: his roles in Gringo, Jack Reacher, and Spooks were written for white actors. So, more recently, were his roles in The Water Man, Come Away, and (obviously) Les Misérables. These didn’t come easily. He campaigned for the opportunities. “I have given my agents a remit to bring me scripts that are not written with me in mind. You have to actively seek out these roles.”

SHIRT ($1,145) BY DOLCE & GABBANA.

His presence in Les Misérables in particular, he points out, probably would not have happened even five or 10 years ago. Thanks in part to the efforts of people like Oyelowo to fight for representation and pursue parts written for white actors, the old norms are shifting. “I think we all ultimately win by normalizing this stuff,” he says. “I look forward to the day when my kids don’t even realize there was a time when people like them couldn’t see themselves reflected in media.”

Helping to normalize that new reality, he says, is one of the things he’s most proud of. “We have to keep going in there and fighting for it, and keeping people accountable to reflect the actual world we live in.”