A Hundred Years Ago, the Bauhaus Was a Radical Idea. Today, It’s Everywhere.

The Bauhaus school closed in 1933 after just 14 years in operation, but its influence remains all around us. In a century that was defined by giant leaps ahead in technology and design, the Bauhaus was there at every turn. Bauhaus, which translates simply to “house of building,” was a school in Germany, founded by the architect Walter Gropius. Gropius had served in the First World War, where he’d seen firsthand the horrors wrought by modern warfare, and was acutely aware of the power of new technology to drastically affect human life. In response to this experience, Gropius was determined to find a way to harness the technological marvels of the 20th century for good. When he was selected to lead an arts school in Weimar, he saw the opportunity to put this idea into practice.

Gropius founded the Bauhaus school in 1919 on the then-radical notion that arts and crafts could be taught and practiced side by side. He sought to blend art and design in practice, using new technology to mass produce objects and create ways of living that would transform the world for the better. Instead of classrooms and classical theory, the Bauhaus favoured hands-on creation in workshops. Instead of siloing its students into single areas, they were actively encouraged to cross boundaries and collaborate, experimenting in metalwork, bookbinding, theatre, weaving, and architecture.

“Let us therefore create a new guild of craftsmen, free of the divisive class pretensions that endeavoured to raise a prideful barrier between craftsmen and artists!” wrote Gropius in 1919. “Let us strive for, conceive and create the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture and sculpture and painting, and which will one day rise heavenwards from the million hands of craftsmen as a clear symbol of a new belief to come.”

The Bauhaus attracted some of the most progressive thinkers in Germany to its faculty, among them the painters Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, the avant-garde choreographer Oskar Schlemmer, and the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Together, through their work and the work of those they inspired, they would lay the foundations for the modern era of design. They would design skyscrapers and appliances, furniture and typefaces, and establish a new design language based on the idea that when form follows function, beauty is the result.

“The principles of Bauhaus are in the chair you’re sitting on, the smartphone in your pocket, the car you drive, and the glass condo tower you see outside your window.”

Not everyone was happy with what was going on at the school. As Germany struggled to rebuild its shattered economy and identity after the First World War, institutions like the Bauhaus were torn between opposing forces of conservatism and liberalism. On one side, conservatives believed in preserving classical German values and rebuilding Germany as a global power, while the progressives on the other side embraced new ideas of international socialism and cosmopolitanism. The firmly leftist Bauhaus—whose members included communists, Jews, homosexuals and other enemies of the burgeoning Nazi movement—had its funding slashed by the right wing local government and was forced to relocate to the industrial city of Dessau in 1924. While this move resulted in the school’s most fruitful and influential period, political pressure from the Nazis forced the school to move yet again in 1933, and close its doors for good a year later.

But the radical ideologies and philosophies that the Bauhaus fostered weren’t so easy to contain. As faculty and students fled Germany and spread across the world, Bauhaus architecture began to appear in New York, London, Chicago, Geneva and Tel Aviv. Former faculty members took positions at other prestigious schools in the US and Europe, and continued to teach, inspiring a new generation of artists, craftspeople and designers.

It’s thanks in a large part from these teachings that the modern world emerged. The principles of Bauhaus are in the chair you’re sitting on, the smartphone in your pocket, the car you drive and the glass condo tower you see outside your window. Wherever functional modernism replaced ornamental classicism, Bauhaus was there.

The buildings and objects that follow represent the places where that ideology was made real. The fact that they remain as vital and fresh today as they were a century ago is a testament to just how powerful those ideas remain.

Dessau School, Walter Gropius, 1926

When the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, Walter Gropius had a clean slate to express his ideas for what an institution could be. The result was a building that embodied the principles of Bauhaus design in reinforced concrete and glass.

“The school itself is an amazing building,” says Peter Clewes, architect and principal of design firm architectsAlliance. “It wasn’t part of any prescribed architectural style. It was really a liberation of cultural expression.”

Designed as a series of overlapping boxes, the Dessau school rejected ornamentation and classicism. Instead of peaked roofs, dormers, and decorated facades, it offered clean lines and a wall of glass panes. In the daytime this glass curtain wall flooded the interior workshops with natural light, and at night made the building glow like an otherworldly object.

“The Bauhaus movement essentially said, ‘We’re going to forget all those rules [of classicism] and build somewhat objectively,’” says Clewes. “‘What is the purpose of the building? And how can we maximize its objective through architecture?’ It sounds like an obvious perspective, but prior to the Bauhaus, no one designed buildings that way.”

Wassily Chair, Marcel Breuer, 1925

In the early 1920s Marcel Breuer, a protege of Walter Gropius, bought his first bicycle. He was impressed by the machine’s simple design, which hadn’t changed significantly in the last 30 years. He was particularly struck by its tubular steel handlebars, which bent gracefully to meet the arms of the rider. With his mind fixed on this form, Breuer set about reimagining the classic club chair, stripped down to its basic elements. With a frame of chromed tubular steel spanned by a sturdy cotton canvas fabric, the Wassily chair was born.

Named for the painter Wassily Kandinsky, a fellow Bauhaus alum, it’s widely regarded as the first piece of modern furniture, and remains as fresh and engaging in the 21st century as it was in 1925.

“Rather than turn to prior furniture design for inspiration, Breuer looked to how the industrial age was bending and shaping raw metal for all kinds of applications,” says Benjamin Pardo, Design Director at Knoll, the furniture company which still produces of the Wassily chair. “When you think about how the primary concerns went from how to carve the most intricate detail into the back of a chair to what minimal combination of materials add functionality and simplicity to a total space, you realize just how pivotal the Bauhaus was for modern design and our everyday lives.”

Tea Infuser No. MT 49, Marianne Brandt, 1924

Despite Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe receiving the lion’s share of credit, there were plenty of women doing groundbreaking work at the Bauhaus at the same time. Among these was Marianne Brandt, who designed light fittings for the Dessau school and went on to run its metalwork shop.

Brandt’s tea infuser, which is included in the collections of both the British Museum and the Met, represents for domestic tools what the Dessau school building did for architecture: it reconstructs an everyday object from basic geometric forms and by so doing, reinvents it.

“The Bauhaus movement signalled a societal change in direction for the creating of things,” says Mike Keilhauer, president of furniture design studio Keilhauer. “It was really about getting to the essence of the thing in a beautiful and direct manner. This shift in thinking continued to evolve over the last century, influencing much of the design that we call modern today.”

Seagram Building, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1958

After settling in Chicago in 1938, former Bauhaus director Ludwig Mies van der Rohe resumed his work revolutionizing global architectural design. By the 1950s, he was considered to be the most important architect in America, and by that decade’s end, he would complete his most ambitious project yet: the 38-storey Seagram building in midtown Manhattan. Designed in collaboration with his protege, Philip Johnson (who created the interior of the famed Four Seasons restaurant on its ground floor), it distilled the idea of a skyscraper to its basic elements and was hailed as a foundational example of International Style. This freed them up to go much taller as well. The bronze-clad building was sleek, formidable and unabashedly modern. It would set the standard for tower design for decades to come.

Glass House, Philip Johnson, 1949

This glass-walled home, set on a pristine wooded acreage in New Canaan, Connecticut, was designed to take full advantage of the surrounding landscape with its panoramic unobstructed views. Philip Johnson, who designed Glass House and lived there, described its style as a mixture of Mies van der Rohe, the Parthenon, and an English garden, but its clean lines and uninterrupted glass facade mark it as a harbinger of midcentury modernism.

“It defined his philosophy of architecture and design,” says Toronto architect Heather Dubbeldam. “It’s almost like an architectural folly, where he’s just playing with an idea. It’s so minimalist… it’s all about proportion and reflection and transparency. It was an expression of modern living, of what we should aspire to, and he took it to the extreme.”

Nesting Tables, Josef Albers, 1927

Adhering to the Bauhaus’ multi-disciplinary philosophy, Albers was a painter and stained glass-maker who incorporated those practices into his furniture design. “In a sense, these nesting tables are a three-dimensional interpretation of Albers’ flat paintings,” says Anthony Barzilay Freund, Editorial Director & Director of Fine Art at auction site 1stdibs. Unlike the work of more traditional designers of the day, Freund continues, Albers’s use of colour was rooted in science and colour theory. “What’s more, the Bauhaus championed the simplification of form and the reduction of excess ornamentation,” he says. “The simple geometries of these stacking tables couldn’t be a better expression of that ideology.”

Vitsoe 606 Universal Shelving Unit, Dieter Rams, 1960

During a career designing appliances, electronics and furniture that spanned half a century, Dieter Rams helped to bring modernism to the masses — even creating a pocket radio that served as a precursor to the first iPod. While he didn’t attend the Bauhaus himself, he worked closely with the Ulm School of Design, which was founded on Bauhaus principles by former students.

Rams was ahead of his time, both in terms of his futuristic designs and the ideology behind them, and he brought the teachings of the Bauhaus into the technology age. He believed that good design did not just result in better products, but was vital to creating a better world. “I imagine our current situation will cause future generations to shudder at the way in which we today fill our homes, our cities, and our landscape with a chaos of assorted junk,” Rams said in 1976. “The times of thoughtless design, which can only flourish in times of thoughtless production for thoughtless consumption, are over. We cannot afford any more thoughtlessness.”

Max Bill, Junghans Watch, 1961

After studying painting and metalwork under Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Oskar Schlemmer at the Desau school, Max Bill moved to Switzerland where he helped to usher in a new era of graphic design. Among his most enduring creations is a series of wall clocks and watches for German watchmaker Junghans, whose clear typefaces and uncluttered designs were a bold departure from classical watchmaking conventions.

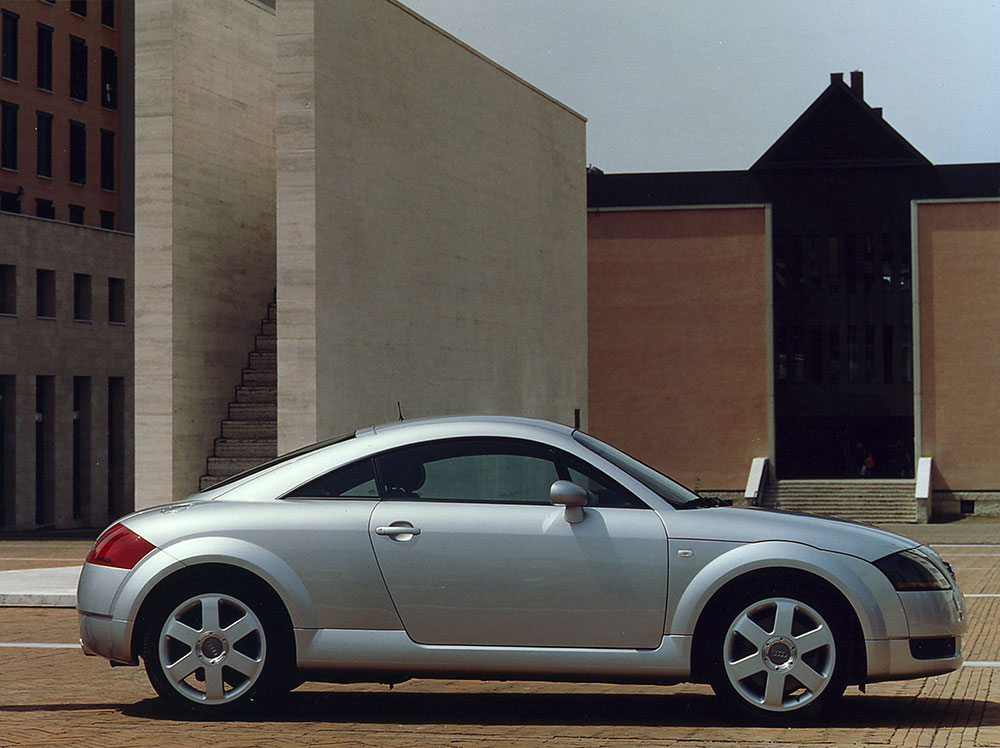

Audi TT, 1998

While the TT may not descend historically from the Bauhaus, it’s not hard to draw a direct line from the work of Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky, and their contemporaries to its main aesthetic elements. “The TT has a clear geometric form with simple clean surfaces, which reflect the Bauhaus principles based on the square, circle, rectangle and triangle,” says Ken Cummings, a professor of Industrial Design at Humber College in Toronto and a former designer for Chrysler. The TT premiered at the 1995 Frankfurt Auto Show as a concept car, and was released to the public three years later with remarkably few changes — a rare testament to the strength of its initial design. “There was a rash of “retro” cars in the 1990s such as Plymouth Prowler, Chevrolet HHR, Chrysler PT Cruiser, VW new Beetle, and Ford Thunderbird,” says Cummings, adding that while the Audi TT fit in with the trend of reflecting earlier automobile designs, it has outlasted all of its contemporaries. Its timeless, Bauhaus-influenced design is doubtless a big part of its continued appeal.

Helvetica, 1960

Among the places that proved the most fertile ground for Bauhaus ideals after the Second World War was Switzerland, where a young typographer named Max Meidinger was working on a new kind of typeface. “Switzerland was neutral in the war and they were able to continue the principles of Bauhaus because their industry was still flourishing,” says Greg Durrell, partner at the Vancouver design firm Hulse & Durrell. After studying at the Arts and Crafts school in Zurich — an institution whose philosophy mirrored that of the Bauhaus in many ways — Meidinger was tasked with creating a new typography that would be versatile, unemotional, and easy to read. The result was Helvetica, arguably the most influential and widely used font of the 20th century. “I think it’s fair to say there would be no Helvetica without the Bauhaus,” says Durrell, adding that the typeface also drew inspiration from the Russian constructivist movement of the early 20th century. “If you look at the design work that began in the late 1800s and progresses towards the 2000s, there’s this lineage of simplification of form,” he says. “Helvetica was the answer to the question, ‘How do you make a typeface that’s devoid of style, that just exists like water?’”