Metallica’s Kirk Hammet Is Obsessed with Horror Like Nothing Else Matters

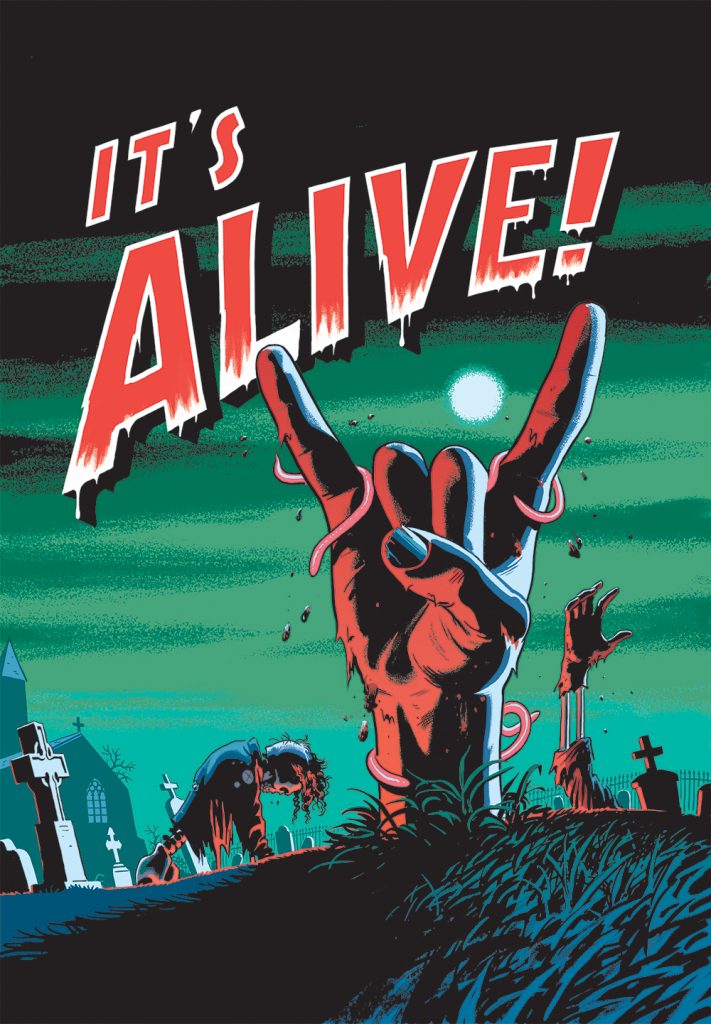

It’s the last stop on Metallica’s North American tour, and Kirk Hammett is about to go onstage in Grand Rapids, Michigan. But first, he wants to talk about art — specifically, his upcoming exhibition of horror and sci-fi movie posters, “It’s Alive,” opening at the Royal Ontario Museum on July 13. Yes, the lead guitarist from Metallica, the most popular heavy metal band on the planet, is curating an art exhibit.

It turns out, Hammett has synesthesia. “When I see things, I hear music,” he says. “When I look at a Cy Twombly, I definitely get some sort of musical rumblings. Same goes for my movie posters.”

At home, he is surrounded by over 1,000 pieces of horror movie memorabilia and artwork, more than 100 of which are featured in the ROM show. Together, they relate a visual history of fear — reminding us that what scares us changes. Hammett is so excited about the exhibit, he is even writing an original song for it — fresh musical rumblings inspired by fear.

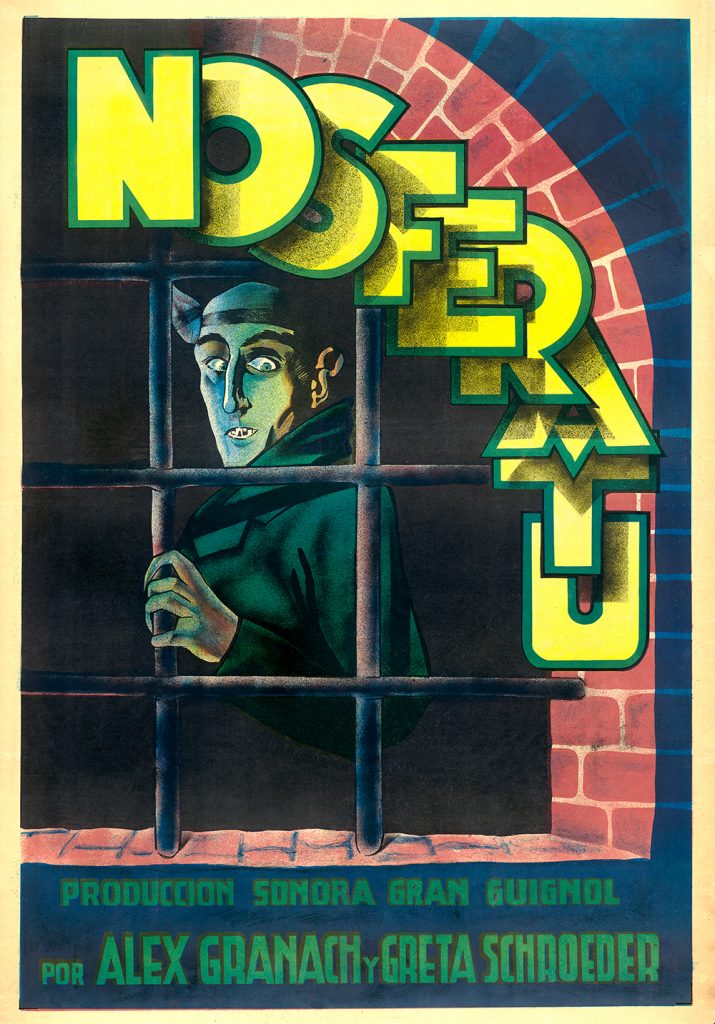

“I’ve been watching horror movies and reading monster magazines since I was five or six,” he says. Classic 1930s monsters — Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, the Mummy — are his favourites. Graphic violence is less interesting to him. Ever since Hammett’s morbid leanings led him to a morgue housing hundreds of bodies, he can’t watch gore movies like Saw or Hostel. “I just think those are boring, and predictable — and not particularly healthy to watch if that’s all you watch,” he says.

In Hammet’s house growing up, there was a lot of jazz, classical, and Rodgers and Hammerstein. When he was 12 or 13, he discovered rock — and found he liked the harder stuff. “Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, Iron Maiden, the darker themes. I thought, ‘Hang on — this is pretty cool, man. This is running along the same lines as all the movies I’ve been watching.’ Then the Misfits came out and it was so blatant. Their font is actually from a monster magazine, Famous Monsters of Filmland.”

Heavy metal sounds frightening. That’s what piqued Hammett’s curiosity: “It’s exciting,” he says. “It’s like I’m on the edge of doing something really dangerous, but really I’m just listening to music. And when it’s over, I’m safe again.” Horror movies have the same effect — the posters serve as a reminder of fears conquered. Plus, they look cool.

Some people are drawn to the things that scare them and can’t look away. Hammett took it one step further, buying the things that scared him, collecting them, and turning them into an art exhibit for all to see. “‘Leaning into it’ — that’s what psychiatrists say,” he says.

He won’t disclose the highest price he’s ever paid for a poster, but he did once consider mortgaging his house to buy a piece. There’s a network of horror collectors, he explains. Many movie posters from the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s were recycled during the Second World War, and when a poster like Hammett’s Dracula three-sheet is found in a projection room at an old theatre in Canada, it sparks a bidding war. “It’s like finding the fucking Hope Diamond! Sometimes I get the piece, sometimes I don’t.”

His wife is cool with his horror obsession, but there are some parts of their house that are designated “clean zones” with bare white walls. “So the sensory bombardment isn’t, like, 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Hammett explains. Darkness exists in contrast to light — you need both.

When Metallica’s concert begins, it is painfully loud. Onstage, Hammett’s happy demeanour is gone. Here, he is a demon, one who deals in killer riffs. His music is the sound of fear being exorcised and, sure, art. And yet, having survived Metallica’s full metal assault, the world seems brighter. The best thing about both heavy metal and horror movies: they end — and then suddenly everything else feels pretty good.