Advice on Life, Style, and Cars From Paul Smith, British Fashion Luminary

It may seem odd to some, to ask a man like Paul Smith for life advice, but hear us out. Aside from being prolifically successful, Smith is quite simply a shockingly nice human being. The reason, by the way, you can immediately tell that he is nice, is because when he walks into our interview he sticks one of his lanky arms above his head and waves, shouting “hi!” from across the vast room in a totally child-like gesture of goodwill. It’s immediately disarming and unexpected not least because, well, he’s Sir Paul Smith: one of British fashion’s most successful designers, and a man who’s still running his own independent company 51 years after founding it.

We spoke to Smith in Munich recently, where he was promoting a sustainably-minded concept car he’d created in collaboration with Mini.

What keeps you going? You’ve done a bit of everything: clothes, bicycles, cameras.

I’m a bit mad, you know. I’ve worked with Leica Cameras, Pinarello bicycles. My company works well. I love my job. So, anything outside of that is just fantastic fun for me. If I can make a little bit of money out of it, that’s great, but that’s not why I do it. I love to be scared. I do a lot of public speaking, and I’m always frightened.

How do you deal with that social fear?

I think I’m just really ordinary with everybody. They’re probably as nervous about meeting me as I am about meeting them, so why not just go, “hi everybody!” I really cite my dad for that.

Your company is still independent, which makes it kind of rare. What’s the value in that?

With my staff at least, I’m well-known as being a lateral thinker, going down the non-obvious route. Yes, I should know what Gucci, Prada, Louis Vuitton are doing, so I know what not to do.

Right. I mean, whether it’s clothes or cars or watches, a lot of products do seem kind of similar.

People are just nervous to be themselves and the whole world is so homogenized. It’s so sad really. Because we’re all, for some reason, trying to keep up and trying to, you know, be responsible to the turnover of the company or whatever — which I understand, of course. When you fight against it, you’ve got to keep your feet on the ground. You can still can have a bit of lateral thinking.

Growing up in Nottingham, in the 1950s, what did cars mean to you?

Cars were completely about mobility, just getting from A to B. I’m not a car-aholic.

So, what interests you about cars now?

What I do enjoy is the form of cars, the shape. My eyes hurt with certain cars, where the proportions are just wrong: they’re too tall or too short. Same with clothes, if the pocket’s incorrect. I mean, I’m a big fan or architecture, Palladio from the 1500s: he was the master of proportion. You can get that from your car or your jacket.

How did the Mini Strip project happen? And, why did you go for this sustainable, minimal concept?

When Mini called me, I said I don’t really want to do something that’s just decorative. Where I work in London, there’s a couple-hundred people in my company, and most of them are young. They’re very conscious about climate change, sustainability, not wasting. So my approach really was, “what if?”

What if?

“What if we took that out? Do we need that? What if we didn’t have, you know, an on-board sat-nav since you already have your phone? The other thing was, what ingredients can the car have that are either recycled or can be recycled.

The unpainted metal body looks cool, kind of worn.

Like your favourite jeans or your suede jacket, it’s always better when the knees are a bit worn out. That’s what’s so great about that unpainted bodyshell. It’s got these funny little worn-out bits or imperfections. I quite like that.

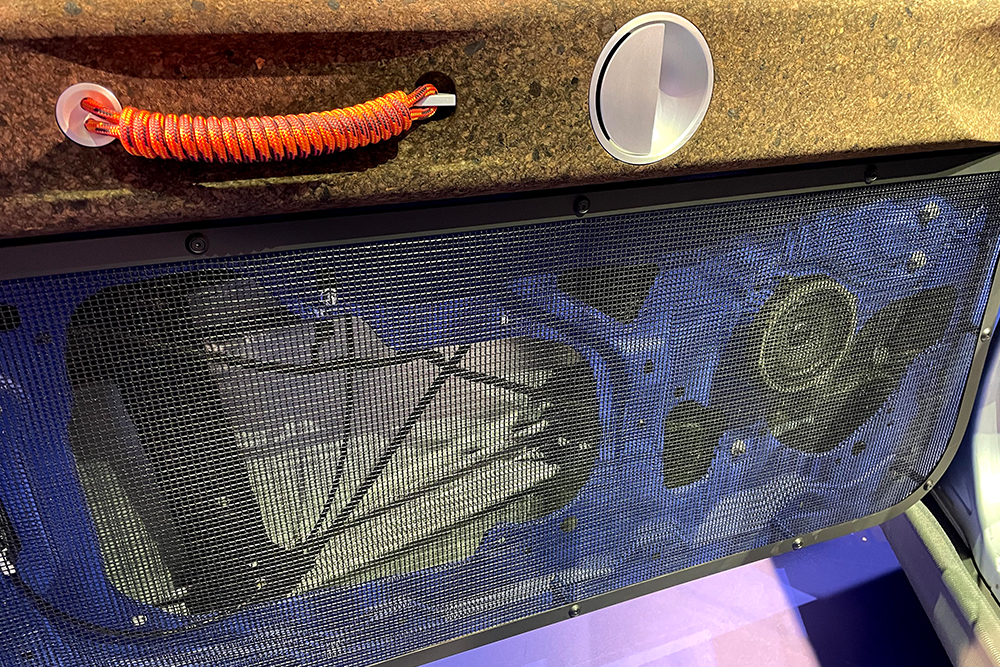

Up close the car has a high-end DIY aesthetic, not your typical high fashion look. How did that happen?

I used to be a racing cyclist and so the tape you put around the handlebars — that’s around the steering wheel. And then climbing rope for the door handle, which again, it’s just that loads of kids at work do indoor rock climbing on the weekends. Those 3D-printed spats [black bits around the wheel arches] can be replaced by anyone with an Allen-key if they get damaged. And the plexiglass roof is recyclable.

Is it important to be able to fix things, to make things?

My dad, you know, he was the sort of man that really never employed anybody to do anything — not because he was mean, but just because he was from a different generation. “So, you need to fix that? Well, I’ll just fix it!” you know? Load of the kids in my building, they build their own bikes, and fix their own bookshelves; they’re very much about keeping it simple. My dad, age 94, he made himself a shoe horn. He couldn’t get his shoes on, so he went out to the garage, cut out some metal, bent it, filed it, just so he could get his shoes on! He could have gone to Woolworths, you know?

Any last pieces of advice for people?

Never take yourself too seriously, and always remember that nobody cares how good you used to be. Keep your feet on the ground. Think laterally. Say please and thank you.

Thank you.

Lovely to see you, thank you.