Sonny Vaccaro has always been a gambler. It began humbly enough, shooting marbles as a child in Trafford, Pennsylvania. Instinctually, something inside him clicked. After graduating high school, Vaccaro and a pair of friends drove to Las Vegas with nothing but a few hundred dollars to their name to seek their fortune. The journey itself was a dice roll of sorts. This was 1950s Las Vegas, after all; no Michelin star restaurants, no Formula One Grand Prix glamour, just gambling in its purest form. At the time, he didn’t have much planned for the rest of his life. He just figured he’d bet on himself.

Vaccaro graduated high school with the third-lowest grades in his class. A star baseball player, he fantasized about going to the majors. It wasn’t until he spoke in front of his peers at a pep rally that a guidance counsellor planted a different seed in his mind. “She said, ‘You speak very well,’” Vaccaro, now 85, recalls. That fleeting moment proved seminal. He realized that as much as he liked to gamble, perhaps his most potent talent was convincing others to roll the dice alongside him.

There are many such tales of Vaccaro’s influence, all of which are detailed in his upcoming memoir, Legends and Soles. Some, the world already knows (how Vaccaro convinced Nike to wager its entire basketball marketing budget on an unproven rookie named Michael Jordan; how he swayed the Jordan family to sign with a fledgling, equally-unproven basketball brand in Nike; how he influenced the Supreme Court to allow college athletes to be compensated for their talents). Others, like how Nike opened an FBI investigation into Vaccaro for corporate espionage following their messy divorce, have yet to be told by Vaccaro himself, until now.

“Gambling is one of the arteries in my life,” Vaccaro says. “There’s no question about it. I think it gave me courage in everything I did. […] I wanted to win the marble game. I wanted to win. No one was thinking about anything in the 50s other than surviving. What’s the best way for me to become somebody? It was sports or gambling, basically. I didn’t know anything else.”

Reading second-hand accounts or watching these stories through the lens of Hollywood cinema (Matt Damon portrayed Vaccaro in 2023’s Air), his story becomes almost hard to believe. It’s the type of “pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps” narrative that’s tempting to scoff at, only because it feels so impossible to replicate. But listening to Vaccaro as we discuss his memoir and, moreover, his life’s work, one sees immediately what his high school guidance counsellor saw decades before.

“If there’s something you want to do, go for the damn thing. There [are] many things I never should have been able to do. I never should have been anything. And I was.”

Sonny Vaccaro

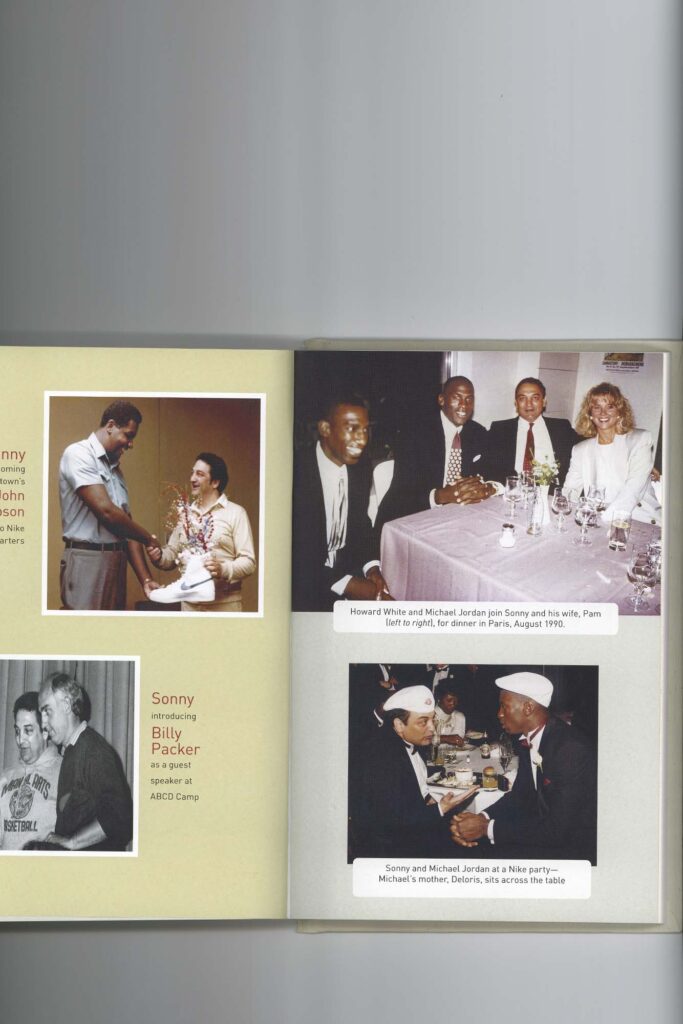

He speaks in a way that makes one lean in, scared that they might miss one of the philosophical nuggets he scatters throughout the retellings of his life stories. That post-graduation pilgrimage to Las Vegas, for instance — the one that, as he explains in the book, helped unlock the rest of his life — could merely be seen as a boondoggle from any other orator. But from Vaccaro, it’s painted as a quest filled with infinite possibilities. He exalts the high school players he invited to his basketball camps as if they all had the propensity to be the next Michael Jordan, if only for a single play. He injects a sort of magic into every chapter of his life, from his chilly exit from Nike to meeting the love of his life, Pam (who he married in Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, naturally — “We won that bet,” he laughs).

Vaccaro approaches life with the type of intention and conviction that not only makes one want to bet on him but, in turn, invites them to bet on themselves. “If there’s something you want to do, go for the damn thing. There [are] many things I never should have been able to do. I never should have been anything. And I was,” he says.

“I’m not a businessman. If I were a businessman, I would have signed contracts for myself much better than I did. I was just a young kid who believed in himself and wasn’t afraid of the consequences. […] Everything was improbable in my life. So, I can’t describe my talent. I just know when somebody has value.”

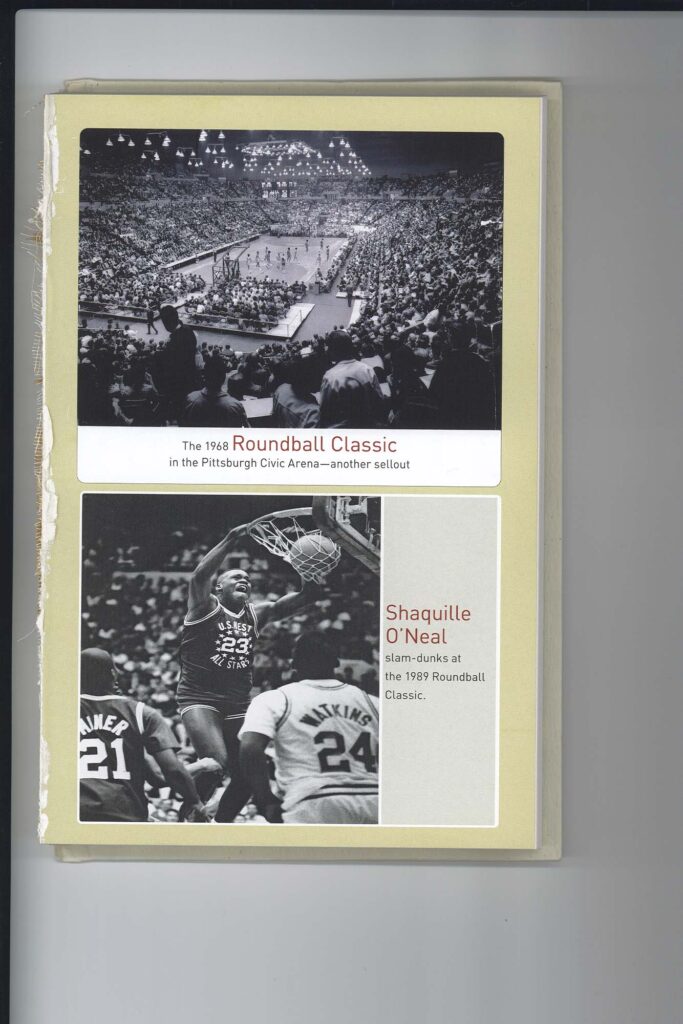

His uncanny ability to perceive value was the foundation behind Vaccaro’s initial career success, garnering Nike’s attention by creating the first high school All-Star basketball exhibition through the Dapper Dan Roundball Classic to start his career. After leaving, he convinced Adidas to sign another unproven young star, Kobe Bryant, urging a second brand to spend the entirety of its budget on a single player (when Vaccaro bets, he prefers to bet the house).

“There’s an inherited genius, no matter how big or small, in all of us.”

Sonny Vaccaro

Throughout our interview, he eagerly credits those around him for a lifetime of success (mostly the players, God, and of course, his beloved wife, Pam). What he can’t humbly ascribe to those around him, he chalks up to the blind faith that fuelled his every trip back to Las Vegas.

“There’s an inherited genius, no matter how big or small, in all of us,” insists Vaccaro. “Some people are afraid of their genius, and they don’t go after that one thing. They don’t go after Kobe [Bryant] or they don’t bet their money on a Michael [Jordan]. But you know what? I believe in the future. I’ve believed that my whole life.”

Featured photo courtesy of Sonny and Pam Vaccaro.