On March 16, 2015, three men walked out of a townhouse on a near-empty street in a quiet Whitehorse neighbourhood. It was the kind of street dotted with postage-stamp lawns and rock gardens, where many homes back onto a forest — a planned community where the streets are all named after birds: Pintail Place, Mallard Way, Goldeneye Street. It had been a mild winter in the Yukon. This particular Monday, the temperature hovered around -8C.

The men all had the sides of their heads shaved, with a flat strip of hair in the middle. They piled into a car and drove off down the street. But, unbeknownst to them, members of the Yukon’s Federal Investigations Unit were watching. As part of a group of RCMP officers who target drug trafficking and organized crime, they’d been investigating these men for nearly a year. Undercover, they had bought cocaine from one of them — Jeffery Redick, a muscular, tattoed 34-year-old from Langley, British Columbia — several times. Redick was a dial-a-doper. He’d run drugs across town, exchanging baggies of cocaine for handfuls of bills, anywhere from $50 for less than a gram to $12,000 for four ounces. He’d bragged to the undercover RCMP officer that he and one of his associates were “the elite.” But dial-a-doping is high-risk work, not exactly Kingpin-level work. Redick was low in the drug-dealing pecking order. But police suspected he was part of a much larger criminal organization that had recently set up an outpost in Whitehorse, and was headquartered in Redick’s hometown.

Whitehorse, a small, sleepy city that had managed to remain largely sheltered from gangs and drugs and violence, had just grown up. Organized crime had moved in.

They called themselves 856. The gang had made headlines in recent years when they expanded and seemed to thrive in Yellowknife, despite multiple police raids. An RCMP officer’s report there on the gang referred to its members as “significant players on the national criminal landscape.” The previous summer, police had seized $400,000 in cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine from a Langley mansion believed to be the gang’s home base. They also found 44 kilograms of phenacetin, a carcinogenic chemical used to dilute the cocaine. Normally, it’s used to deworm pigs.

That night in March, as Redick drove along Mountainview Drive, a dark, steep road that connects Whitehorse’s outlying neighbourhoods with its riverside downtown, police were following him closely. He had at least two tails, but likely didn’t know it until officers swerved in front of him to cut him off. Redick allegedly tried to drive through the tactical takedown, but couldn’t break through the police-car barrier. The officers arrested him and his two passengers, a 33-year-old who was couch-surfing at the townhouse, and Taylor Wallace, a 23-year-old, also from Langley, who was suspected to be Redick’s boss — the leader of the local 856 cell. The real elite.

RCMP officers went back and raided the townhouse, finding loaded handguns and rifles, rocks of cocaine — enough for up to 90 individual sales, when broken down — ecstasy, $20,000 in cash, ammunition, a plane ticket in Redick’s name, and gangland swag: black T-shirts emblazoned with “856” in white lettering. Police arrested a fourth man that night, and in the coming weeks, they arrested eight more. Most of them, like Wallace and Redick, were from the Langley area.

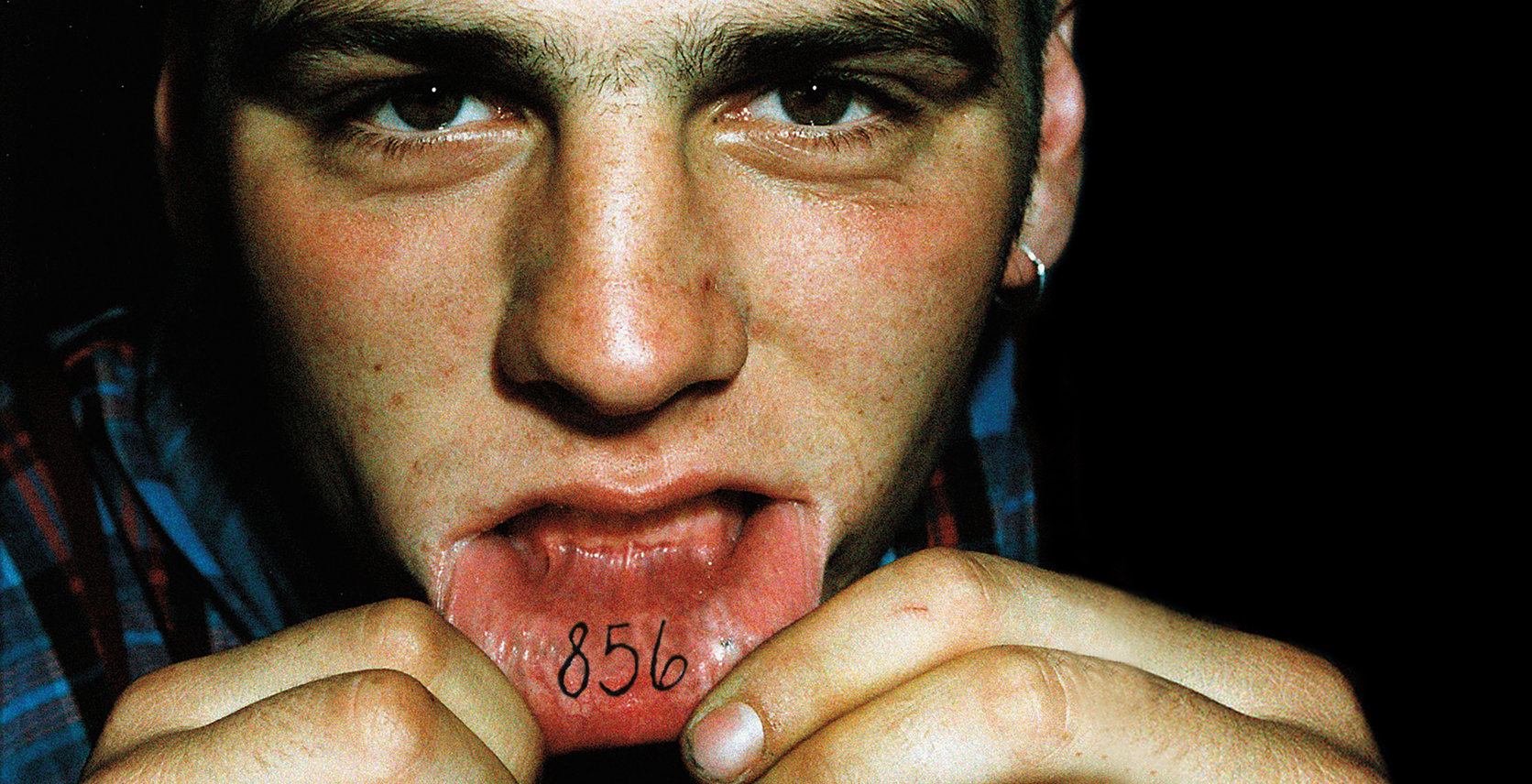

On Redick’s inner lower lip, police found an “8” tattoo. Another suspect bore an “85” in the same spot. Taylor Wallace had the full “856.” It was the trademark branding of 856, where dial-a-dopers get the first digit, before graduating to middle management, running a dial-a-doping cell and adding a “5.” The top members, those who oversee a whole region, have all three digits. The ink — which the officers got warrants to look for — confirmed investigators’ suspicions — though the revelation was still shocking. Whitehorse, a small, sleepy city that had managed to remain largely sheltered from gangs and drugs and violence, had just grown up. Organized crime had moved in.

…

NESTLED IN A RIVER VALLEY, surrounded by mountains, Whitehorse is home to just 27,000 people. The capital has big-city amenities — chain stores you’d recognize, hipster bars you wouldn’t, and thriving arts festivals — but a small-town feel. People stop on the sidewalks to chat. It’s not unusual to see the Yukon’s premier in Tim Hortons picking up his morning coffee. It’s no utopia, though. The Yukon has the third-highest crime rate in Canada, after the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. But the most common offences aren’t the work of calculated criminals. Mischief, disturbing the peace, and property crime violations like break-and-enters are often the unfortunate symptoms of untreated social ills: addiction, mental health issues, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). At the Whitehorse Correctional Centre, an estimated 90 per cent of inmates have substance abuse issues. A preliminary government study found 18 per cent have FASD. The Yukon has the highest rate of impaired driving in the country. The crimes are troubling, to be sure, but rarely deadly, and often not malicious in intent. From 2011 through 2013, there were no homicides in the territory.

Drug dealers have always prowled the territory’s streets, filling the demand for an illicit high, as they do in most Canadian communities. But historically, these criminals have been locals who want to make some cash selling small quantities of cocaine, marijuana, ecstasy, meth, or crack. The RCMP and Crown prosecutors know these dealers. They recognize them as they cycle in and out of jail.

“We can only presume that 856 saw an opening, because a lot of people were dying, and it was very chaotic in their world.”

By late 2013, Whitehorse’s drug market had shifted from small-time dealers to something more structured. Yukon RCMP conducted one of the biggest-ever busts in the territory that year, arresting several men with links to BC-based crime groups who were transporting kilograms of cocaine north from the Lower Mainland, via delivery drivers, breaking the bricks down into smaller amounts, and selling them on Whitehorse’s streets. One dealer was moving two kilograms every 10 days, raking in about $90,000 every month.

Remote northern communities are lucrative markets. When oil and gas prices soar, populations boom. People have money to throw at the boredom and isolation they live with. Gangs are attuned to fluctuations in the economy, as well as news of police raids and arrests in other cities. They’ll eye new territory like a business owner would consider buying a new franchise. It’s not uncommon for gangs to send members on scouting missions to survey the market. If they see an opening — few local dealers, or prices they can undercut — they’ll swoop in, recruiting the existing dealers or muscling them out with threats and violence.

Just six months after that winter bust, 856 was active in Whitehorse, selling smaller amounts of cocaine, grams and ounces. With the big-league dealers off the streets, the gang saw an opening and made their move. They used a convenient dial-a-doping business model: customers call a number, place an order, and arrange a quick pick-up. The men who migrated to Whitehorse were young, in their 20s and 30s — hardly established career criminals. When the 856 suspects appeared in court after the arrests, some could have passed as teenagers. But appearances can be deceiving. 856 was madly efficient, muscling its way into multiple northern communities within a span of just a few years. They brought with them guns and drugs, both likely acquired from a large organized-crime group in the Lower Mainland — like the Hells Angels, who control BC supply chains, sell to smaller groups like 856, and, the RCMP suspects, directed them to move into the North.

…

IN 2007, 856 were just a few punk teenagers in suburban BC who spray-painted buildings and bullied other kids. Richard Konarski was an inspector at the Langley RCMP detachment at the time, overseeing several units. In late 2006 and early 2007, teachers at the local high school told him about a group of male students who were causing trouble, starting fights, and stealing lunches. Konarski didn’t pay much attention — it was just kids being kids.

But then officers in the drug unit started hearing about the same students. They were calling themselves 856 now, after the phone number prefix for Langley’s Aldergrove community. One of the suspected members’ fathers, Len Pelletier, allegedly had ties to the Hells Angels, and the young men used his name to intimidate and threaten rivals, according to Konarski. They became emboldened, fast. In June 2007, in the early-morning hours of a high school graduation party in Langley, a kid was stabbed. An 18-year-old named Jason Wallace, Taylor’s older brother, was charged with attempted murder.

The possibility that innocent people could get caught in the crossfire was frightening. This wasn’t just disturbing the peace. It was suddenly serious.

Three months later, while Pelletier was dropping his son off at school, someone ran him off the road and fired several rounds into the side of his Hummer. Police said it was potentially 856-related. After the shooting, Konarski called a meeting with all of his teams. “Our job is to obliterate this group,” he told them. “We’re going to take them out.” They constructed a profile of the 856, focusing on six friends and family members between the ages of 15 and 18 who seemed to be the core members. That year, they arrested all six. Some went to jail, while others transferred to different schools. Konarski thought that was the end of 856. He and his officers moved on to other crimes, other suspects. For his part, Pelletier, who survived the attempted hit, doubted Konarski’s entire premise. “It’s something the cops concocted against a group of kids,” he told the Vancouver Province, “They made it seem like they had a gang. And even if they did, they definitely don’t now. There is no such thing as 856 anymore.”

In the meantime, a conflict that had been brewing between the Lower Mainland’s biggest gangs boiled over. The region is home to several organized-crime groups, from lowly street gangs to heavy hitters like the Hells Angels. The biker gang is highly organized, with chapters across the country, and has a hand in more crime than you might think. “Most people say, well, the Hells Angels don’t affect me, so I don’t give a shit about the Hells Angels, but they do. I mean, your children are getting dope in the schools that most likely comes from the Hells Angels,” Len Isnor, a detective sergeant with the Ontario Provincial Police, told author Jeff Pearce in his book Gangs in Canada. They’ve been active in the Lower Mainland since 1983. For years, they had little competition.

As the illegal drug trade boomed in British Columbia, gangs in metro Vancouver realized the big money that could be made, particularly by exporting marijuana. More gangs started sprouting up. The United Nations was first, in 1997, followed by the Red Scorpions in 2000, and the Independent Soldiers soon after that. All these gangs had their own allegiances, their own motives. In the fight for control of the multi-billion-dollar trade, the fragile calm between the groups fractured; on one side were the Hells Angels, Red Scorpions, and Independent Soldiers — known as the Wolf Pack Alliance — and on the other were the United Nations and several Indian crime groups. In 2009, a full-on turf war erupted. Gang members and associates on both sides of the divide were gunned down in broad daylight, in front of grocery stores and in parking lots. The first two months of the year saw more than 30 shootings, 12 of them fatal. The bloodshed garnered international media attention, from CNN to The Independent. “As police, we’ve always been told by media experts to never say or admit that there is a gang war,” Vancouver police chief Jim Chu told reporters. “Well, let’s get serious. There is a gang war, and it’s brutal.” As people were shot and others arrested, the organized-crime landscape was in constant flux. 856 was about to make the most of it.

“We can only presume that 856 saw an opening, because a lot of people were dying, and it was very chaotic in their world,” says Staff Sgt. Lindsey Houghton of British Columbia’s anti-gang agency, the Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit, who suspects the fledgling gang, like other mid-level groups, pays a tax to the Angels in exchange for permission to exist under the biker gang’s nose in Langley. That year, Konarski was surprised to hear about the gang in the news. He thought he’d busted the lot of them, and hadn’t heard the numbers “856” in a while. But they were like a cancer, resilient and resurgent.

…

IN APRIL 2015, Jeffery Redick was in custody at the Whitehorse Correctional Centre. It was a month after the raid. He faced 17 charges, from cocaine trafficking to evading police. A judge had imposed no-contact orders between him and his 11 co-accused, so they had to be kept apart within the small jail, which typically houses about 90 inmates. He’d spent time in jail before. In 2009, he was sentenced to five months for a drug-related offence in Surrey. He’d grown up in Langley, raised by a single mother. It’s not known when or why he came to the Yukon. His lawyer later told a judge that he has no ties in the territory, just some friends. His presence in Whitehorse dates back to at least 2006, when he and another man were charged with assault causing bodily harm after an alcohol-fuelled brawl at a dance inside a hockey arena.

On the night of April 17, 2015, Redick was in the common area of the men’s unit at the Whitehorse jail. Three other inmates quickly approached. Redick didn’t stand much of a chance. They beat him with weighted socks, cracking his head open. He was shipped across town to get stitched up at Whitehorse General Hospital.

In the Yukon, the kingdoms might be small, but if you’re running things, it still pays to be king.

The three men allegedly belonged to a rival gang. They and five others had been arrested in connection with a robbery about three weeks before the raid against 856. Two men, Benjamin Harper and James Graham, had entered Kustom Phone Repairs, wielding a machete and a baton, respectively. They demanded cash from the shop owner and two employees, one of whom was pregnant, and fled with $310 and an iPhone.

The robbery was only the latest in a string of crimes and suspicious activity over the previous month. In February 2015, RCMP raided a storage locker and seized an AK-47, a sawed-off bolt-action rifle, ammunition, and 37.5 grams of amphetamine. Five days later, officers showed up at the Whitehorse airport in body armour, carrying rifles, in response to a report of a man carrying a gun. Police located the suspect, instructed him to lie down, then searched him. They didn’t find a gun, but there was a knife in his pocket, along with two cell phones, and 6.5 grams of cocaine. Twenty-seven-year-old Gerrit Houben-Szabo was charged with trafficking, released on bail, then re-arrested weeks later in connection with the 856 investigation. He was a dial-a-doper who’d sold cocaine to an undercover officer multiple times.

Then, late one night, two weeks after Houben-Szabo’s arrest at the airport, gunshots rang out across the parking lot of the Yukon Inn, a Whitehorse hotel that sits at the foot of the clay cliffs skirting the downtown core. Someone inside a blue van had fired at a man and woman walking near the hotel — she was hit, but survived. The brazen violence was uncharacteristic of Whitehorse, and residents were concerned. Rumours flew that two gangs from Outside were feuding, big-city drug dealers using Whitehorse’s quiet streets as a battleground. The possibility that innocent people could get caught in the crossfire was frightening. This wasn’t just disturbing the peace. It wasn’t just disorderly conduct. It was suddenly serious. Police never commented on the feud theory. They released a fuzzy surveillance photo of the blue van speeding out of the parking lot. To this day, no one has been charged in connection with the shooting.

…

IN MARCH 2016, Redick pleaded guilty to cocaine trafficking and possessing firearms without a licence. His fingerprints had been found on one of the rifles inside the townhouse on Pintail Place. His lawyer told the judge that Redick has been working toward his GED at the Whitehorse jail, and when he gets out, wants to return to Langley and go to school to become a barber. He wants to put the criminal life behind him, his lawyer said. He was sentenced to three-and-a-half years behind bars, minus time already served.

Taylor Wallace, the alleged leader of the gang’s Whitehorse cell, pleaded guilty the same day, though not to trafficking. He hadn’t been present during any of the undercover officers’ purchases, and there wasn’t hard proof he had been involved in drug dealing. “Regardless of the tattoo, the evidence the Crown has on Mr. Wallace is probably the least amount of evidence we have against all the co-accused because he was only found getting out of that residence,” said Crown prosecutor Eric Marcoux. It’s how gang structure is supposed to work, insulating senior members from serious crimes. Wallace only copped to careless storage of firearms. He received six-month sentence.

Cracking down on gangs is like cutting off one of the heads of the Hydra, the mythological Greek monster — two more spring up in its place. Putting gang members in jail only creates more business opportunities for others. “You’re kidding yourself when you think that if you wipe out one gang, that’s the end of it,” says Konarski. Perhaps that’s why, despite the arrests in Whitehorse last year, strange happenings continue. The body of a convicted cocaine dealer was found in the woods, his pickup truck abandoned on a side road. Two men were injured in a volley of bullets at a downtown intersection early one winter morning.

It’s easy to see why the North appeals to a gang like 856. First, critically, demand is high. Second, the region is miles from the congested Lower Mainland, where 856 would be considered a kind of kid brother to the Hells Angels, Red Scorpions, and United Nations. In the small ponds of remote communities, the group can be a big fish and wield real power through its supply of drugs from the larger groups, notoriety with which it can intimidate local dealers, and a core of members who view themselves as brothers. In the Yukon, the kingdoms might be small, but if you’re running things, it still pays to be king.