Six Iconic Canadians Share Their Lessons of Fatherhood

Being a father is the biggest thing I’ve ever done. It feels like the only thing I’ve ever done. It never ends. And it’s the heaviest thing, the most rewarding—a work in progress and a job, especially now, that gives no breaks. My father used to say that he was a better man than his father, and that I’m a better man than him. He meant it in the best possible way, I think. Each generation, for better or worse (but mostly better), gets more sensitive, my dad means.

I only hope my son is a better father than me. That’s what I want for father’s day—my children to have peace (and if I get some too, and an edible and a little Scotch, that’d also be good). Reaching out to men across the country, I spoke to filmmakers, musicians and a politician admired for his honesty in the search of what fatherhood makes a man—it isn’t only having children, it’s what we do with the children we have.

Bruce McDonald

Filmmaker; movies include Pontypool (2008), Roadkill (1989), Hard Core Logo (1996), This Movie is Broken (2010), and Dreamland (2020).

“What struck me about being a father was how many stories you told. You start somewhere with the dragon and the clerk at Shoppers Drug Mart and she takes you far away, to the ice cream castle. I love that. Being a father you plant a seed, and now my girl’s wearing a Ramones shirt so, you know, all good. My dad had four kids and worked pretty hard and went to night school. You didn’t get to hang with him as much. Having only one kid, I spend a lot of time with my daughter and I think of what my father taught me: finish what you start. Really, that’s become a mantra for me. Working on scripts and projects, it takes forever, but: “finish what you start.” When I think of my dad I thank him for that. I try to apply it with my daughter. Even if it’s riding bikes to the park—you don’t want to be the guy who forgets. Men should know that rather than chaining you down, kids are a passport to adventure. I remember Francis Ford Coppola was asked once what advice he’d give a young filmmaker. He said, “Have a family.” I didn’t understand what he meant until I had my daughter, but now I get it. It makes you a better person.”

Shad

Musician; albums include A Short Story About War (2018), Flying Colours (2013), TSOL (2010) and The Old Prince (2007). His Netflix series is called The Hip-Hop Evolution.

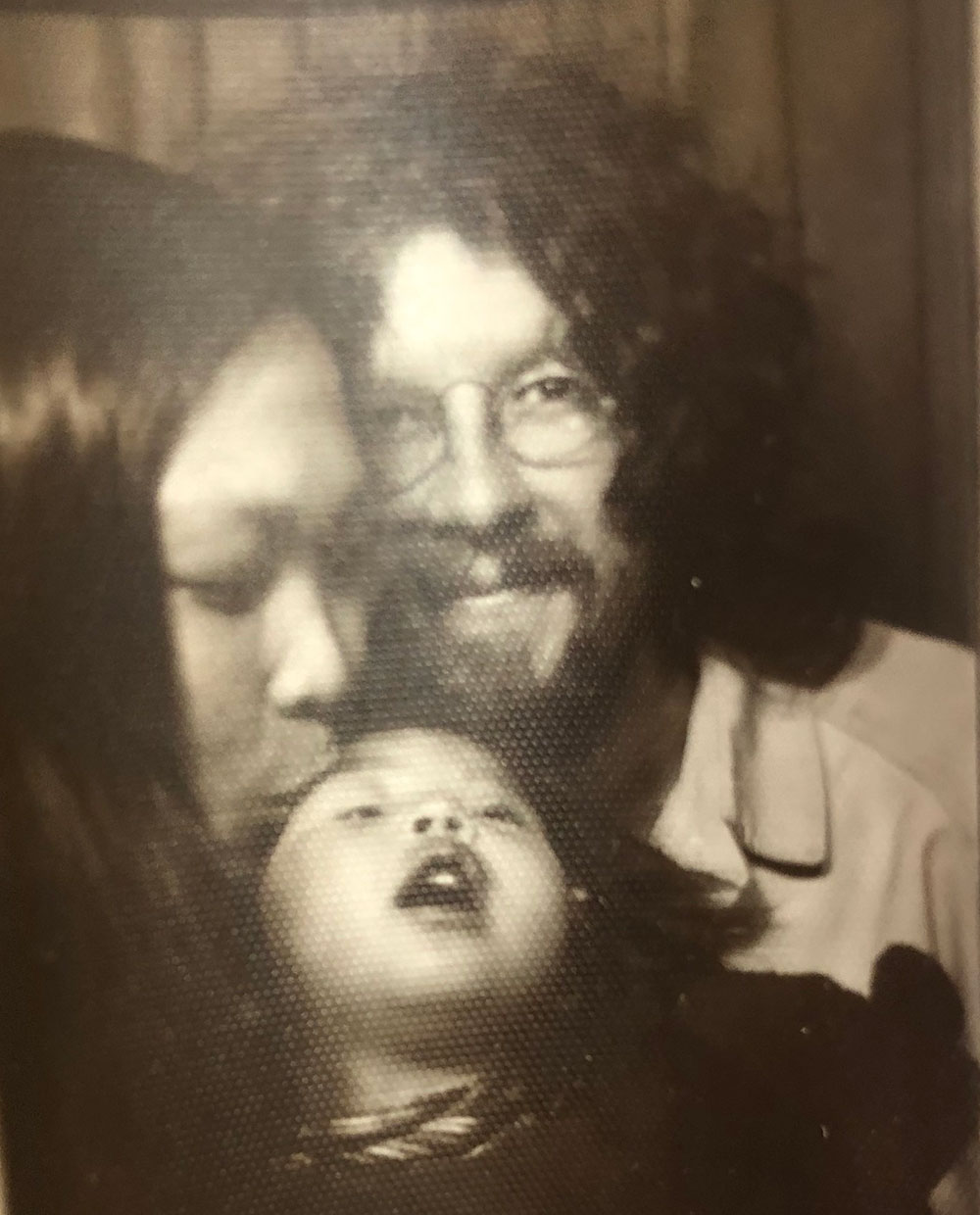

“You see your kid and they’re small and cute, they’re simple. You get to have this relationship with them, hold them and laugh at them, care for them. It’s hard to find the exact words for the feeling—it’s just cool. You created this life. You’re part of this bigger thing. Prior to that, your world is just you, maybe your partner. But then it’s something bigger—your life is bigger: it’s big.

The thing I think about with fatherhood is contentment. I like my life with Amara in it. It feels complete. Full. When I think about my own dad, I think: consistency. He wasn’t a dad I played ball with all the time or enjoyed a million things with, but if my bike was broken, I had confidence that by the end of the weekend, it would be fixed. If I had a friend’s birthday party, I knew he wouldn’t forget. I knew he’d know how to get there. He has integrity and a commitment to his family that I could always trust.”

Gordon Lightfoot

Musician; records include Back Here on Earth (1968), Sundown (1974), East of Midnight (1986), A Painter Passing Through (1998), All Live (2012), and Solo (2020).

“I try and stay in touch with my kids. I have six grandchildren, one 1-year-old great grandchild. You learn from all of them. Oh, I didn’t know anything when I started. I didn’t pay nearly enough attention and I’ve been in a state of repentance ever since. I tried not to stay on the road too long. It’s a learning process, fatherhood. It’s a job you grow into. Which kids need attention, which ones are OK. A couple of my kids hardly need me at all. I’m learning from them these days. One kid’s in construction, one works for the government. I have two grandchildren that work for the TTC. She drives the bus. She has one kid and is on her way. They all are. And of course I’m proud of them. They’re pressing forward. The job of being a father requires patience. You have to try and stay in a good state of mind. The future’s uncertain, it always has been, but it feels even more like that now. The world could probably stand to have more good fathers. I feel pretty confident that my kids, my grandkids—these men—will do the job better than me.”

Matt Galloway

Radio host; The Current, CBC Radio

“The things that you thought were important before kids aren’t as important after they come. Be present and focused, that’s what I tell myself. That’s what the job is. And the job doesn’t get any easier. My kids are teenagers now and it’s hard—it’s not them, it’s me. I’m always worried that I’m failing them; that I’m not doing enough. You have to be around. The hard conversations don’t come at the dinner table, they come late at night. You have to let your children be candid. They will model their behaviour on what they see you do. What do you value? How do you live? My children force me to be better all the time.

My father was aware of that, but in a different way. He was a draft dodger that moved to Canada and made a new life here. He was involved in the Civil Rights movement and thought carefully about who he was and the values he subscribed to. When things kicked off in the states, I immediately called him. I grew up in a house where everyone was involved, but parenting isn’t equal—women carry the burden. Dads are trying to work harder and figuring out how to be their best selves. At our house, nothing is off the table and there’s a window of immunity: we can talk about things without consequences. I want them to know when things fly off the rails—as they will—they can come to me.

Trust takes time. You have to be humble. You can read all the books, but be willing to learn; you can get better at being a dad. It’s a long game. Whatever it is, my children know we will work it out.”

Andy Maize

Singer, The Skydiggers; records include Just Over the Mountain (1993), There and Back (2000), Northern Shore (2012), Let’s Get Friendship Right (2019).

“Dad passed away two years ago this coming August at the age of 93. He’s still looking after us. I think he was most himself on the golf course. Even as an adult, I used to caddy for him. Riding in the car was a time of conversation. It was about spending time together and I appreciated that. I’ve tried to do that as a father. Often the best moments are when you’re not trying to make a point: nothing can replace the time you spend with your kids. I’ve learned along the way there’s life and there’s death and then there’s everything else. We have a son, Owen, who’s 21, he just finished his third year in sport management at Brock University. A first child, our daughter Chi Lin had a very difficult birth. She was deprived of oxygen and had cerebral palsy and passed away before her third birthday, in 1998. You want your kids to be happy and healthy and I believe if you provide leadership by example, your children will find their way. My wife Andrea was pregnant with Owen when Chi Lin died and it was a hard time, but she shined a wonderful light on our lives. And after grieving for the challenges she had to face, we realized she was a gift. We knew we had to appreciate every moment—be in every moment with your children. Don’t be worried about what might happen and the things you can’t control.”

Harjit Sajjan

Minister of National Defence, Canada

“Whatever fight my kids have in this world I support them. As a parent, success to me is raising kids with a good heart. A good heart is the most important thing. I taught my children not to look at colour, but look at the person—both of my children have friends from other cultures and that makes me proud. If everyone raised their kids to look at people in an equal way all of the problems with racism in this country would be solved.

My dad pushed me hard. Most of my strength comes from my mom—and my dad will admit that—but I learned discipline from my father. How not to walk away from a challenge. The most racism I ever felt was when I joined the military. My regiment was great, but basic training was where racism hit me. I told my father I wanted to come home. He said I could, of course. But if I did that, if I left, every other minority group would be labelled as a failure by my leaving. It was my choice. But he spoke from experience. He was looking into my future and telling me challenges are going to come your way. Don’t walk away. And I try to pass that on to my own kids.

Those first-generation immigrant fathers, they see themselves through the lives of their children. My sister is far more successful than I am. She’s on her third high-tech company. I was five when I moved to Vancouver. My parents couldn’t speak English well. But integration happens and I’m proud of what my parents went through and the toughness they taught me and the tools I learned from them that I’ve passed down to my own children.”