How Pro Sports And Politics Are Hopelessly Entwined

Sports and politics can make for an awkward mix. These are games, after all, that are intentionally frivolous. Their primary appeal is as a distraction from the messiness of the world. And so barging in with talk about conservatives and liberals, tax-cuts and income inequality, can feel like a tactless intrusion — like bringing a copy of Fast Food Nation to a pizza party or being that jerk that hands out toothbrushes on Halloween.

This fall, however, with elections on both sides of the border, fans across North America have been subjected to the time-honoured tradition that is political sports pandering. In August, all three party leaders took turns jumping on the Blue Jays bandwagon, showing up at the Rogers Centre in the hopes of absorbing some refracted affection from fans in the political battleground that is the Greater Toronto Area. Habs fan Justin Trudeau kicked off the campaign by conducting his a pre-debate interview from a boxing ring (a callback to perhaps his most successful political moment, when he won a charity boxing match against Patrick Brazeau, thus allowing patriotic citizens across the country to vicariously live out their fantasy of punching a senator in the mouth).

“For athletes who care about particular causes, stadiums and arenas aren’t places where politics are ignored, but places where a message can be amplified.”

For American politicians, having a home team is like having a home church: a prerequisite for office, even if you’re not really much of a believer. Jeb Bush is an avowed Marlins fan, Chris Christie has an embarrassingly friendly relationship with Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, and Marco Rubio has long touted his Dolphins mania (he has an “an almost encyclopedic memory of Dolphins trivia,” his aids gushed to the New York Times).

Of course, sports pandering must be done with care. Fans are quick to sniff out bandwagoners or frauds. It’s why Harper’s weirdly bloodless hockey fandom is so in keeping with his particular political style. He’s a guy who loves the game — wrote an entire book about it!— but whose official response, when asked to name a favourite team, is delivered via spokesman: “The Prime Minister cheers for all Canadian teams.”

If done properly, though, a performance of fandom is an easy way to signal all sorts of appealing personal characteristics. Name-checking your favourite Cub or most beloved Pistons benchwarmer is a stand-in for values like authenticity and loyalty. It’s also a mark of normalcy that makes a politician seem a little less like an egomaniac Brahmin and a little more like just regular folks. If the question in politics is “who would you most like to have a beer with?” being able to talk sports goes a long way.

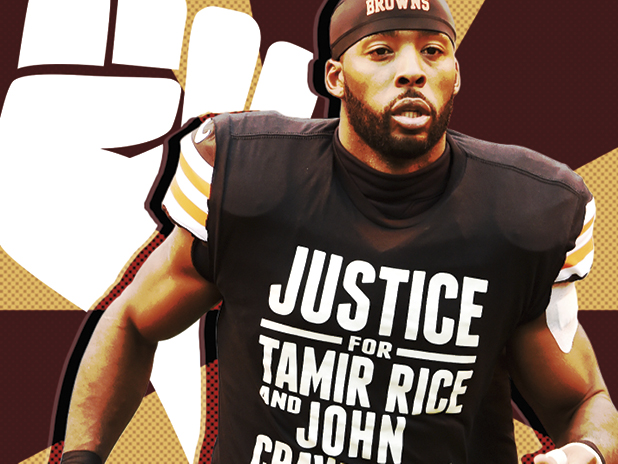

While fans can be wary of politicians trying to lash themselves to more popular athletes, they have often been even more skeptical about athletes who bring their politics onto the field. Since the ’60s and ’70s — the era when Mohammad Ali protested Vietnam and Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in the black power salute on the Olympic podium — sports have settled into a long period of quiet, apolitical money-making.