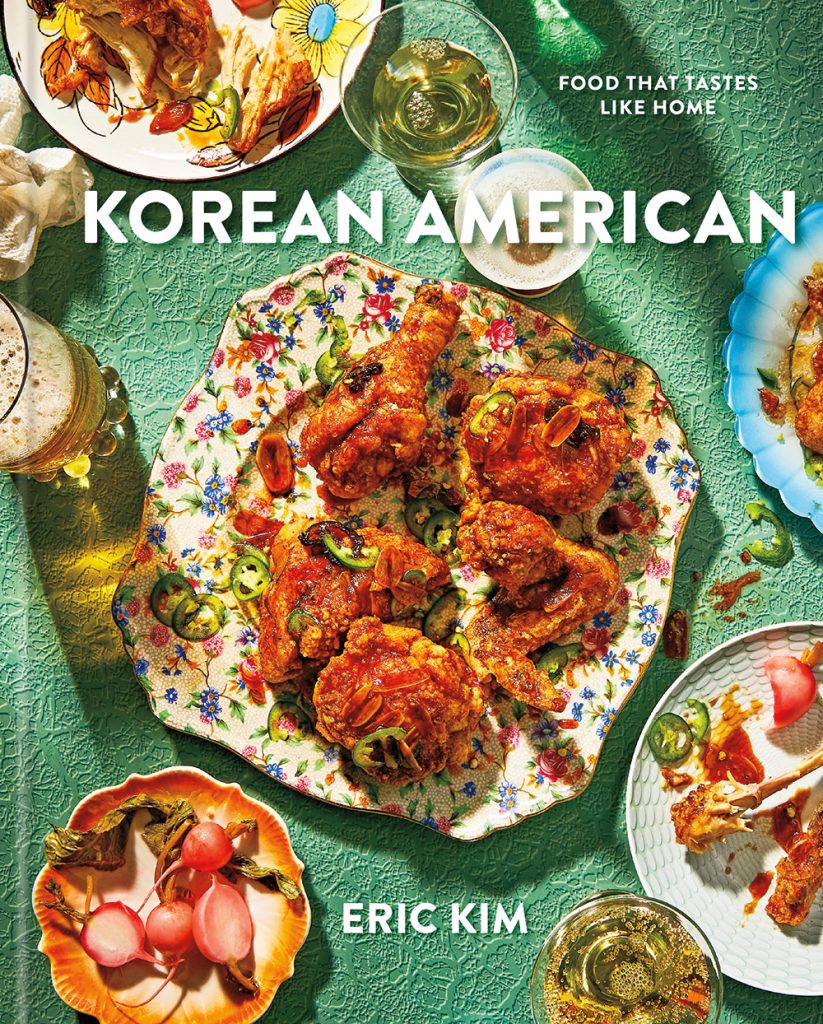

Eric Kim on His New Cookbook and Cooking That Transcends Borders

Eric Kim’s personal experience as both a chef and the son of immigrant parents informed the recipes included in his debut cookbook. With Korean American, Kim — who previously won over a legion of fans as a food writer for the New York Times and a columnist for the New York Times Magazine — has completed his biggest project to date, blending narrative and gastronomy, all with an emphasis on authenticity. Here, Kim breaks down the inspiration behind his varied roster of recipes and discusses the lasting impact of a childhood and life spent navigating two distinct cultures to form a third identity as a Korean American.

Why do you feel like now is the right time to release your debut cookbook? How long have you been perfecting its recipes?

I think, from a personal perspective, I’ve been trying to write a cookbook for a few years, but I needed to find my voice first, and I was able to do that with a couple of jobs I had before I got to the Times. Also, the year I spent back home with my mom was a real masterclass in Korean home cooking. I am thankful I got to do that first, before I wrote it. I think that was very imperative, not just for the recipes in the book, but also to the story, because the book narrates the discovery of someone who’s going back home and asking their parents how to cook certain dishes from their childhood. That’s the perspective I wanted to get across, which is that of a non-expert. I wasn’t an expert in Korean food — and I’m still not — but what I was trying to document were the things I was able to translate from my mother that I learned during that process.

Is it nerve-racking to pen all these personal anecdotes for the world to read?

I really think of the personal essay–memoir genre as a form of writing that requires conscious editing. Even though I am sharing intimate details, they’re ones that I’m carefully choosing; there’s a lot of holding back, which is something people might not know. What you see on the page is a lot of intimate detail, but I see it as servicing the story and the writing. Even though it is a personal narrative, my hope is that, if I’ve done my job effectively, people will read it and think, “Oh, that’s like my family.” That’s very important to me. I’ve also never had this much room to write anything. Knowing that the audience for my book was more expansive than the built-in readership of a specific publication was freeing, which is reflected in the prose — there is a little messiness to it that I like.

What I love about food writing is that it sort of mirrors real life if the text is well-written. I love when I read an essay or a book about a culture that I may not be a part of, and I feel like I somehow know it, which is a very generous thing to offer as a writer. I try to make people feel that way when I can.

Was there one recipe that ignited the idea to create a cookbook?

There is not one specific recipe, but it is more of a platform to showcase the flavour combinations and techniques that I’ve been doing for a while, which are quite quirky. I put roasted seaweed in everything, and I always fortify it with sesame oil and salt, because that’s what makes Korean seaweed so much different than Japanese nori. There’s no flavour that is more Korean than sesame oil, salt, and seaweed. The book documents a lot of the family recipes I grew up eating, but there is also a simultaneous effort to develop unique versions of my childhood favourites or improve the experiments I would make up as a teenager. It’s a mix of old and new.

Also, rather than thinking I had to perfect anything, it felt nice to write down how my family and I eat, which is constantly evolving. Some of the recipes are very new, while others are very old, which is an authentic snapshot of how a family’s dinner table evolves over time.

What would you like readers to glean from this cookbook?

I’ll say that, emotionally, getting to the end of the book-writing process felt so healing. I thought, “Wow, I just learned a lot about myself and my family.” I figured out how I want to move around in this world, which is without whitewashing my Korean ancestry or feeling that I must make up Korean parts of me that aren’t authentic. There’s a sense of ownership of this third identity, Korean American.

It can be hard for children of immigrants who are straddling expectations from both cultures — living your life feeling like you don’t belong in either place is a difficult place to be in. However, there is a changing climate of identity politics, and people are making more room for intersecting identities. Trying not to define entire cultures and cuisines as monoliths is something that’s important to me. Both Koreans and non-Koreans are asking these questions of me all the time. “Which one are you?” And I say I am both and neither at the same time.

What’s your go-to recipe for, say, impressing a small dinner party?

I would choose the jalapeno marinade chicken tacos. They’re just universally good. The marinade is very vibrant and herbaceous, with the perfect amount of garlic. When it cooks, it mellows out, and you can make as spicy as you’d like. There’s also this cooling watermelon salsa, which I dress like a Korean muchim, and if you have a well-made flour tortilla, it’s amazing.

I would be lying if I said I wasn’t trying to impress people with food when they come over, but I do think my approach is less flashy and more focused on something tastier and more balanced. I think simple is elegant, and when you’re able to pull off food that is straightforward, it really resonates. I would describe the book as food that tastes like home, rather than trying to be something it’s not.