Art Meets Tech at Aga Khan

Range Rover & SHARP

Toronto’s Aga Khan Museum is at the forefront when it comes to integrating cutting-edge technology into its exhibitions in order to create immersive experiences for modern audiences.

Consider Shezad Dawood’s “Night in the Garden of Love”, a recent exhibition that featured a two-player VR experience inspired by Yusef Lateef’s novella. It also included an AI-generated scent garden created in collaboration with DSM Firmenich and algorithmically generated plant forms that respond to musical scores. The exhibition blended traditional art forms, such as textile paintings, with contemporary digital elements, offering a futuristic interpretation of garden spaces.

“Everything is a continuum and everything’s connected. You can’t be where you are now if you didn’t have what you had before.”

Marianne Fenton, Special Projects Curator at Aga Khan.

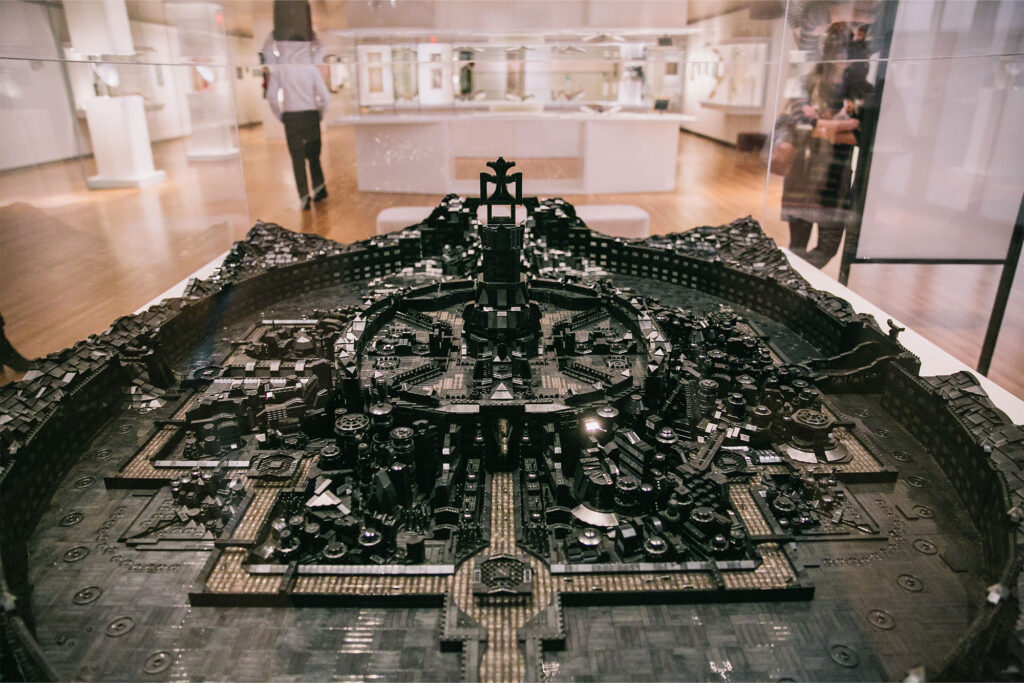

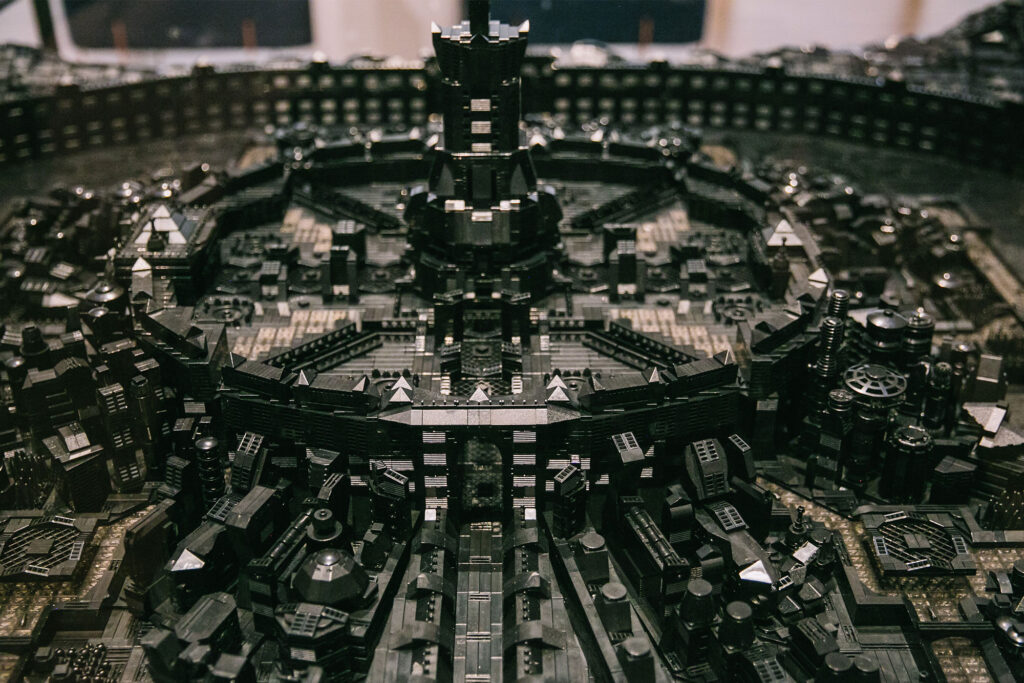

“Remastered,” meanwhile, used digital technology to explore and restore Persian, Mughal, Indian, and Turkish paintings. Ekow Nimako’s “Building Black Civilizations” featured black LEGO sculptures with global interactive workshops. “Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time” included live-streamed tours of medieval Saharan art, and the “Rumi” exhibition offered interactive timelines and explores translation issues in his poetry.

To explore how the Aga Khan Museum connects historical art with modern technology and appeals to 21st-century visitors, we sat down with three key figures who have helped make the space what it is today: Curator Michael Chagnon, Special Projects Curator Marianne Fenton, and Director of Collections and Public Programs Sascha Priewe.

What perspective helps organize the history we see at the museum?

“I think we view the broad history of the art we show, from the earliest moments of Islamic civilization in the 7th century up to the present, as a continuum and a continual story,” explains Chagnon. “We’re always seeking ways to use our collection to explore the arts and stories around art that show connections between cultures across time.”

“We think about these broad continuities over the centuries. We don’t have an artificial divide at the modern period where things suddenly become different. We like to tell stories with broad historical scopes, starting at early moments and following up through the present as an ongoing narrative.”

“Something we strive to do in pretty much all our exhibitions is to connect the past with the present, with the future,” adds Fenton. “We have this amazing permanent collection, and we like to be able to bring it into conversation with contemporary work.”

“The reason we do this is because we believe really strongly that there’s a kind of a misconception that there’s art for the past, art for the present and art for the future. Everything is a continuum and everything’s connected. You can’t be where you are now if you didn’t have what you had before. Technology wouldn’t be technology if it wasn’t built on rug weaving, and zeros and ones, and computer technology. And even a lot of the work in our permanent collection that looks old would have been a technological advancement of the time. Printmaking revolutionized the way people received material and what was able to be disseminated and created because of the printing press. That was a technological advancement, much like AI is a technological advancement now. I think we have a chronological snobbery. We think that what we’re doing is new.”

So, technology – something that can be used to create art in the present – can play a strong and natural role in explaining history?

“It’s a really interesting experience to have AI and virtual reality in the spaces alongside analog works,” says Fenton. “One of the reasons why we’re so keen to bring in AI, virtual reality and more futuristic ways of doing exhibitions and artists’ work into the Museum, is that it also attracts new audiences. It sort of breaks open that idea of what a museum looks like and what your museum experience is going to be when you get there… I think, we have a very narrow idea of digital and AI.

“Virtual reality is incredibly collaborative. It’s a team of people doing it. That goes from ideation in an artist’s mind or someone’s mind, to the actual coding right at the end of it. Then, of course, bringing it into a space and making sure it continues to function is even part of that collaborative process. It’s not just putting paint on a canvas and on a wall, one and done, there it is. It requires continuous collaboration. For us as a museum, everything is about that collaborative process.”

“And this is not technology for technology’s sake,” adds Priewe. “It’s about meeting audience needs and expectations. During the pandemic, many museums shifted to digital, making great advances, but now some are retreating to analog experiences. We say no. The new normal for us is building digitally-based engagements, meeting audiences globally with different storytelling for different purposes. This must happen on-site, off-site and online – also globally. We constantly refract our activities through this prism of possibilities, always audience-focused. We know certain platforms aren’t for everyone, but they will reach those we want to. We’re constantly evolving as new audiences appear and bringing along our loyal supporters with new experiences.

“It’s about meeting people where they are, their learning preferences and needs, and carrying them along in the stories, also creating with them. It’s not a one-directional affair, and we use many technologies to do that. From analog, hands-on, art-based experiences in galleries to immersive VR experiences, online games and more. The idea is to provide deeper levels of engagement beyond the gallery, with expected interactivity constantly evolving.”