Piping hot and out of a box — until now, that’s likely how’ve you’ve had saké. One sip and it seared your tongue — and for good reason, because if you actually tasted it, you’d have spewed it out faster than a Tokyo bullet train. Most of what the Western world knows about saké is completely wrong. “As a general rule, if saké is being served to you hot, it’s probably low quality,” says Greg Newton, head brewer at the Ontario Spring Water Saké Company. “It’s made with unpolished rice, contains lots of brewer’s alcohol and is hot to mask the off flavours. Premium saké is almost always served chilled.”

While often referred to as rice wine, saké is actually a brew, in that it’s fermented from a grain, rather than grapes. Brewers polish the grains to remove the fat-laden outer coating. They then steam the starchy core, adding yeast and koji — rice that has mould cultivated on it, which converts the starch into sugar, allowing for fermentation to happen. Aging, often followed by filtering and pasteurization, come next. With the current rise of Japanese Izakaya bars in North America, high-quality saké — not futsu-shu, the cheap, scalding dreck— is more readily available than ever. It also comes in a dizzying array of varieties, so a primer on the good stuff will serve you well.

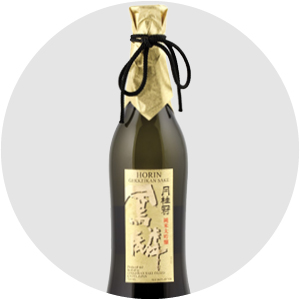

Junmai Daiginjo

If the back of your saké bottle says junmai, you’ve got the best of the best. It’s the Japanese word for pure sake, meaning it has only four ingredients: rice, water, yeast and koji. Besides purity, premium saké is also gauged by how much the rice has been polished, which results in cleaner, more delicate notes. If the grains have been milled to about 50 per cent of their original size, the saké qualifies as daiginjo. A good example, like Gekkeikan Horin Ultra Premium Junmai Daiginjo Saké ($43), will taste full-bodied, fruity and nutty.

Junmai Ginjo

Like junmai daiginjo, junmai ginjo is pure saké. But the ginjo part means the rice has been milled to about 60 per cent of its original size. Like Naga Oze Beishuika Junmai Ginjo Saké ($28), this type is often flowery and smooth.

Namazake Junmai

Yet another factor is whether the saké’s been pasteurized or not. If it’s unpasteurized, and it’s pure, the drink is called namazake junmai. It’s hard to find, unless you know of a local saké brewery. “The stuff imported from Japan is definitely pasteurized,” says Netwon. “We don’t filter or pasteurize ours to preserve the natural flavours.” Nama Nama Saké by the Ontario Spring Water Company ($13) is easy drinking, with prominent tropical fruit notes and a dose of fresh acidity.

Honjozo

Saké that’s been milled to about 70 per cent and had a pinch of brewer’s alcohol added during fermentation is called honjozo. The alcohol is added to help pull out different flavours. A top-shelf one, like Takatenjin Sword of the Sun Tobuketsu Honjozo Saké ($21) will have strong floral and spice notes.

What to pair with saké (besides the obvious)

“Sushi is the food pairing everyone thinks about, but saké is much more versatile than that,” says Newton. “If a saké has a higher acidity, it can be served with blackened cod. Our Nama Nama Saké pairs really well with oysters. Lots of izakayas pair it with fried chicken or fried squid. Personally, I’ll drink saké with pizza.”