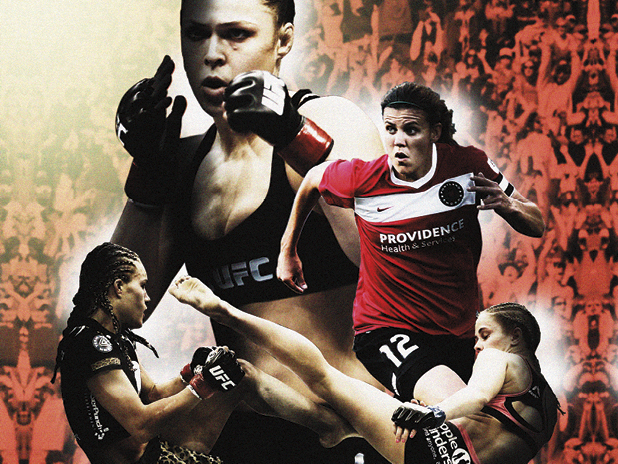

Equal Fights: Women’s Sports Don’t Get the Respect They Deserve

For Christine Sinclair, the pattern must have been disheartening. In 2010, the Canadian soccer star was at the top of her game, playing with the kind of dominance you expect from one of the greatest players of her generation. In that year’s championship game, Sinclair scored twice, leading her team FC Gold Pride to victory. That offseason, her team folded. So Sinclair flew across the country, joined the Western New York Flash and led them to a championship the next season, earning the finals MVP award after scoring the game’s first goal and netting another in penalty kicks. That offseason, the entire league folded.

And so it went—a player who couldn’t be stopped on the pitch was finding it increasingly difficult to find a field worthy of her skills. It felt like a terrible waste, as if Willie Mays had been confined to the Negro Leagues or Meryl Streep had been stranded in some small-town community theatre, performing dramatic feats on a stage too small for her talents.

Sinclair’s battle is the same one so many female athletes face: a fight to stay relevant or even employed in a fan culture that, traditionally, simply hasn’t cared about women’s sports. You see it in basketball, where WNBA teams struggle to bring in crowds, and in hockey, where players who were adored during the Olympics suddenly find themselves working full-time jobs in order to play in the Canadian Women’s Hockey League. A few months ago, when Boston Blades forward Janine Weber scored a dramatic overtime goal to win the Clarkson Cup (the league’s version of the Stanley Cup), the Hockey Hall of Fame asked her to donate her stick. Weber had to think twice. CWHL players pay for their own equipment and giving up the historic keepsake would leave Weber with just a single stick for her next tournament.

It’s impossible for women’s sports to gain respect if they’re presented as a curious sideshow.

This month, then, when Sinclair and the rest of the national team take to the field in the World Cup, it could mark a highpoint for Canadian women’s sport. The team’s performance in the London Olympics—a gritty run that included a Sinclair hat-trick in a semi-final game seen by 3.8 million Canadians—brought new homegrown attention to women’s soccer. The media-shy Sinclair has (reluctantly, begrudgingly) become a household name. Her face is plastered across newspapers and magazines. It’s on the evening news and all over your television in Mazda commercials.

Perhaps more importantly, though, when the World Cup hype ends and Sinclair returns to her club team, it will be with the Portland Thorns, a team The Guardian had called the first “real club” in women’s soccer. It’s a team that brings in 13,000 people a game, attracting rabid fans from well outside the traditional soccer-moms-and-their-daughters demographic. The team’s owner, Merritt Paulson, also owns the MLS men’s team, the Timbers, with whom the Thorns share a stadium. “The club crest is up on the side of the stadium, the same size as the Timbers’ crest,” Paulson told the football magazine Eighty By Eight recently. “It’s not a side project. It is as full-on as we can make it.”

And this may be one of the secrets. In the endless chicken v. egg arguments about the lack of popularity of women’s sports (is more exposure necessary to make women’s sports popular or do news organizations and sponsors ignore them because there’s no interest?) one thing is clear: it’s impossible for women’s sports to gain respect if they’re presented as a curious sideshow. They can’t be Batgirl to the Batman of mainstream male sports—the half-hearted, pitiable female version of the real thing.

In tennis, where the women’s game is as competitive and compelling as the men’s, there isn’t a lesser “Women’s Wimbledon,” held a week later and only covered in the pink ghetto of espnW. Serena Williams plays on the same courts as Roger Federer. She’s given the same television coverage and earns the same prize money. Presented as equals, the audience treats them that way.

Nowhere is the effect of this attitude clearer, or more surprising, than in the UFC. Mixed Martial Arts would seem like an unlikely sport for female athletes. It’s a machismo world in which the only women present were once scantily clad “octagon girls,” a sport whose signature move, the “ground and pound,” features one fighter sitting on top of his helpless opponent, punching him in the face until a burly ref intervenes. In 2011, a TMZ reporter asked UFC head honcho Dana White when women would be allowed into the UFC. White didn’t miss a beat. “Never,” he said, grinning widely, his bald head gleaming in the light of the camera. “Never.”

White deserves some credit for his fast turnaround. Just a few years later, Ronda Rousey is perhaps the UFC’s most bankable star, male or female, and the league has introduced a second weight-class for women, aiming to build on the popularity of Women’s MMA. As in tennis, female UFC fighters aren’t relegated to their own b-list tournaments. They fight on the same card as men, are given the same absurd reality-TV shows, and are promoted with the same over-the-top enthusiasm (although, it should be noted, with a particular emphasis on charisma and sex appeal).

On a spring evening a little while ago, in the midst of the NBA and NHL playoffs, my girlfriend and I walked down to a Toronto bar to watch UFC fight night. The bar was filled with young fans drinking pitchers and eating chicken wings, chatting idly as strawweight fighters Paige VanZant and Felice Herrig appeared on the big screen.

In 2011, a TMZ reporter asked UFC head honcho Dana White when women would be allowed into the UFC. White didn’t miss a beat. “Never,” he said.

In the lead-up to the fight, there had been some online grumbling about VanZant, a pretty blond 21-year-old who some felt was being unfairly promoted because of her photogenic charms. When the fight started, however, those concerns quickly disappeared.

In the first round, the bar oohed when VanZant threw her opponent, a twist of the hip that sent the taller Herrig tumbling to the mat. They cheered when VanZant picked her opponent up by her legs and slammed her head into the ground. The two guys next to us—Oxford-shirt-wearing twenty-somethings who had spent the first fight of the night discussing the relative merits of this year’s crop of superhero TV shows—suddenly snapped to attention. “The other one’s actually doing pretty well,” one Oxford Shirt said, generously, as Herrig lay on the mat, gamely fighting off blows.

By the third round, VanZant was having her way with Herrig, whose face was bloodied and swollen. “Oh my god,” said the other Oxford. “Keep doing it girl, keep doing it,” his friend said, in the blood-thirsty, totally engrossed way of fight fans.

They didn’t comment on her looks or question whether she would stand a chance against a male MMA fighter. They watched the fight, whooping as one tiny fighter beat the hell out of another. It sounded, in its way, like progress.

Nicholas Hune-Brown is Sharp Magazine’s sports columnist. Read more of his work here.