How a New Generation of Restaurants Are Changing the Way We Eat

This summer I made a pilgrimage to Paul Bocuse’s namesake restaurant in Lyon. Chef is now getting on in years, and I wanted to eat at his temple before he no longer cast a shadow over the kitchen. Dinner was everything you might expect from a restaurant that has held three Michelin stars for 55 years: the plush, over-the-top décor of the dining room; the paintings gifted to the chef over a lifetime of work; the reverent hush of the diners; the trolleys laden with cheeses and desserts; the food, classically French to its core, delicious and rich in technique. I left lamenting the fact that no one does this anymore.

It would be all but impossible to open a restaurant like that today. For one thing, it would be too expensive: food, labour, rent and upkeep costs have all continued to rise over the years. But finances aside, there just wouldn’t be customers. As the Boomer generation wanes, so does the demand for places like Bocuse’s (look at high-profile restaurant closings this year, like Toronto’s Splendido). Gen Xers and Millennials — the two generations forcing so much precarious social change right now — are interested in less garish concepts.

Most restaurants opening these days are geared toward the dining habits of younger clientele, because they’re being opened by people in those younger generations. The baton — or chef’s knife — has been passed. We want simpler rooms, with a sense of authenticity. We favour under-design as opposed to over-design. We want food that is tasty and clever without being fussy. We want to share things. We’re not interested in California Cab; we want smaller producers from lesser-known pockets of the world. We crave things that have a story of craftsmanship behind them. While most of us trained in old-school Boomer restaurants, those places didn’t reflect anything about us. So we started building something else.

For me the transition began with a thought over 10 years ago. In 2005, while living in LA, I started the business plan for what is now Model Milk. I would spend five more years in old-school restaurants before I finally got the opportunity to open a place that reflected my personality, my sensibilities. In the original business plan, I wanted an Airstream diner from which I could serve fried chicken alongside foie gras and truffles without anyone batting an eye. (Trust me, at the time it was a very original thought.) The minute we opened Model Milk, we noticed that 90 per cent of all starters were being ordered on Seat 9. (Seat 9 is Model Milk–speak to indicate that the items are to be shared at the table.) After about a year, 50 per cent of mains were also being ordered on Seat 9. Younger guests were using the restaurant differently. They wanted different things from the experience. They liked that we were leaving them open to decide what kind of an experience they could have. Over the course of the next year, as the restaurant’s reputation grew, older generations began to embrace the change, too.

For all us new chefs and restaurateurs, this gave us more flexibility in conceptualizing our places. Gone were the tablecloths, the 100-page wine lists, the tens of thousands of dollars in porcelain, crystal, and silver. Waiters shed the tuxedos and suits in favour of raw denim and Chuck Taylors. The music got turned up, and we weren’t afraid to play the Pixies or J Dilla. We weren’t afraid to put our personal tastes on display. Mostly, we ditched the idea that restaurants should be about worshipping food — and figured they should be more about straightforward pleasure. Millennials want things on their own terms, both as employees and as consumers. And now that they’re running their own shops, it’s OK to admit: the kids are alright.

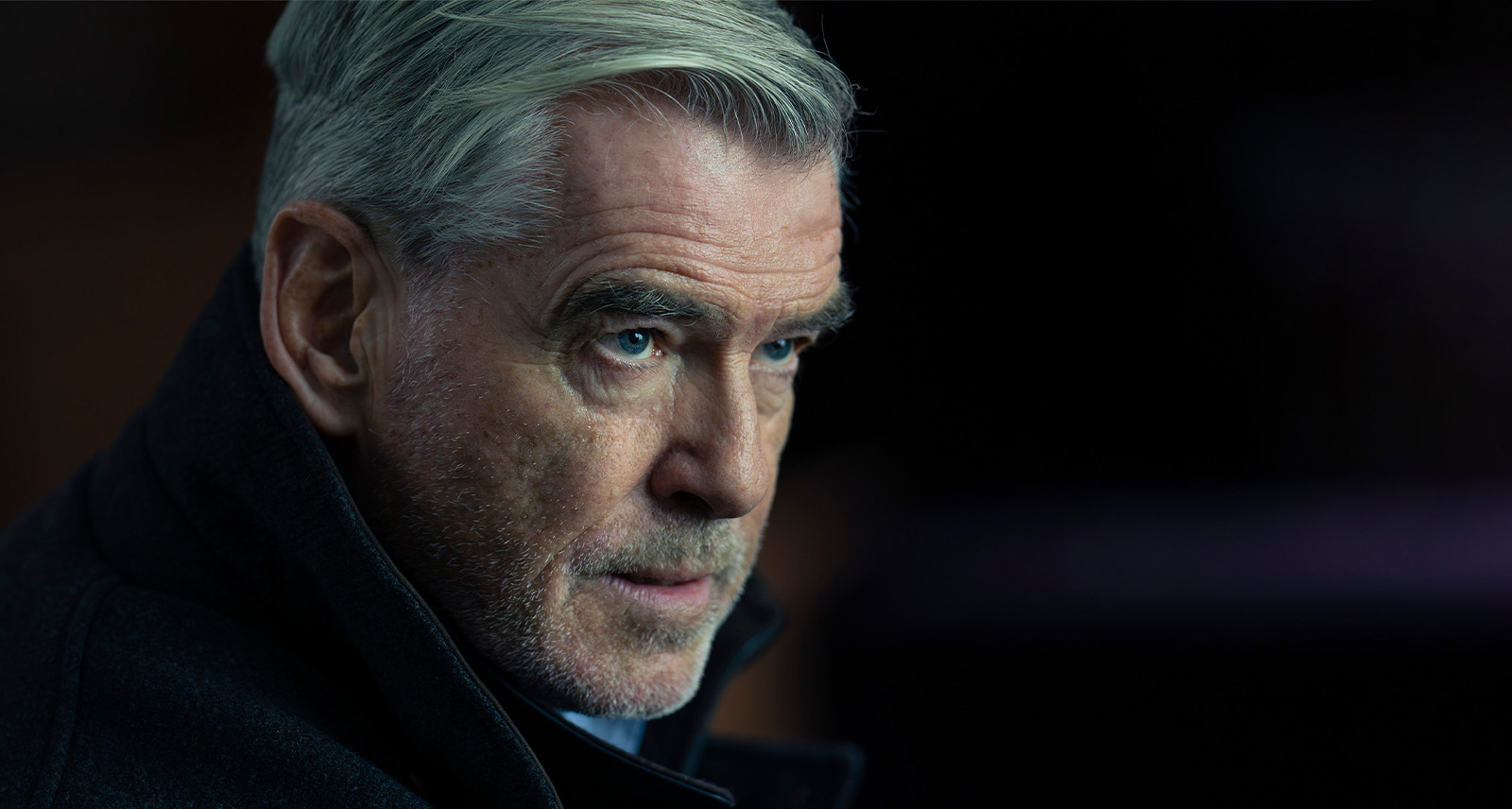

Justin Leboe is the chef/owner at Model Milk and the recently opened Pigeon in Calgary.

Tasty Right?

Like Sharp on Facebook and get more of the same served up daily.