Jock Talk: What Happens When Pro Athletes No Longer Need the Media?

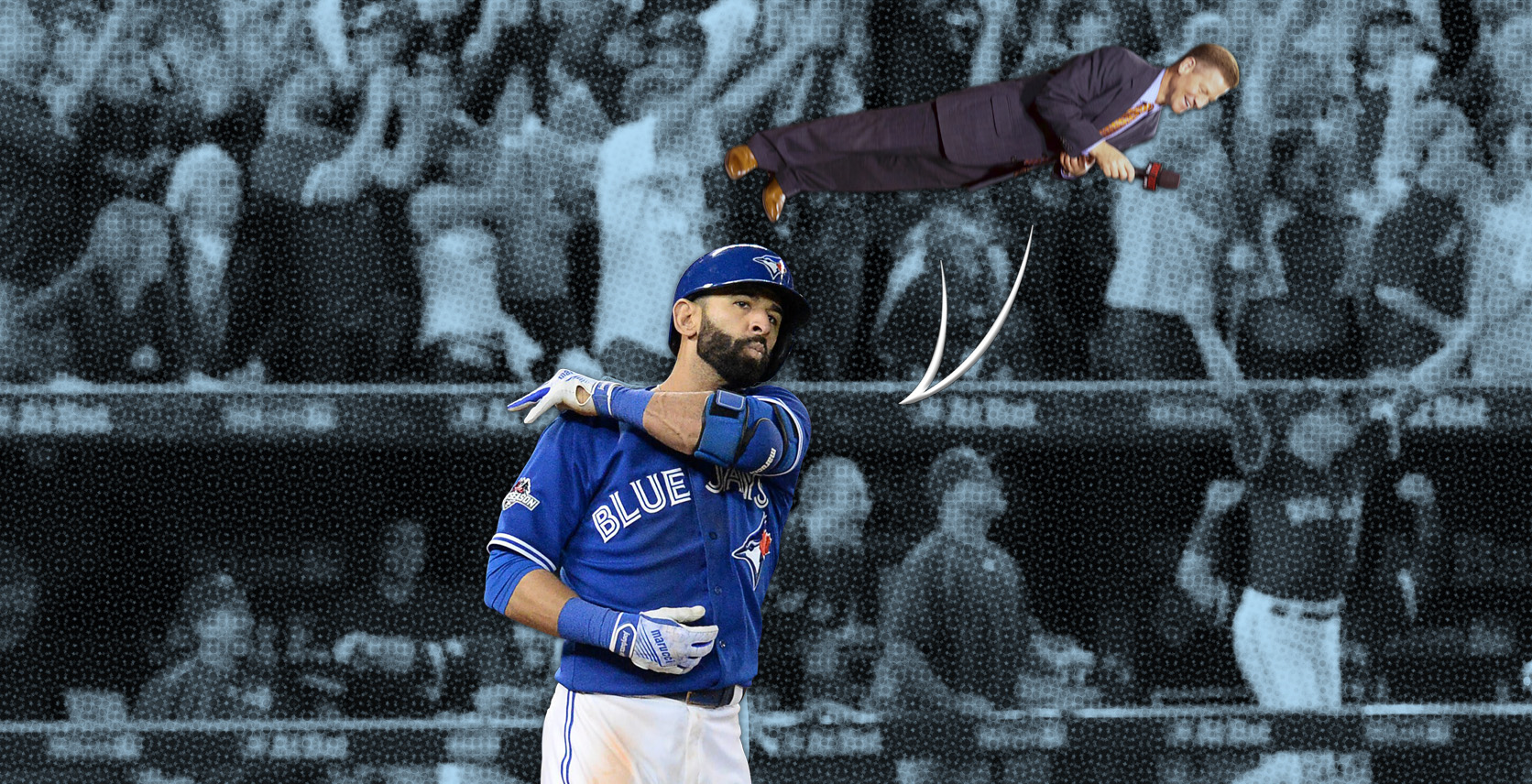

One day in Dunedin, Florida, this February, a USA Today reporter named Ted Berg approached José Bautista for a quick quote. Four months had passed since game five of the ALDS, “the bat-flip game,” and Berg was curious about what the Jays slugger had to say about his historic homerun. It was the kind of innocuous transaction that happens a thousand times a season — the exchange of a sentence or two for one of those breezy, inconsequential stories about training regimens or expectations for the season that fill the back pages of a newspaper sports section. Bautista, however, wasn’t interested.

“What I say doesn’t matter, because you’re going to do with it what you want, so I don’t want to waste my time elaborating,” Bautista told the reporter. “It doesn’t matter. If I would say it, I would say it in my own direct line to fans, so I know it’s not going to get misconstrued…. I’ve got a couple more followers, I believe, than you and maybe all the media in here combined, so I’ve got a bigger reach. More people are going to listen to what I say on my direct line anyway.”

Bautista’s response was jarring. Why not simply play along with the age-old journalist-athlete game the way that Aaron Sanchez and Russell Martin did in the same piece? Give a pleasant quote. Talk about being in the moment or the importance of teammates or any of the other safe clichés. Instead, Bautista acknowledged a truth that has become painfully obvious but is usually left unsaid out of some mixture of politeness and embarrassment: players no longer need the media. And in the sports industry — a business built around a series of staged events that exist solely as media moments — no one knows quite what comes next.

•••

THE CRACK IN the athlete-media compact have been showing for a few years now. In 2015, when the NFL forced Seattle Seahawk Marshawn Lynch to speak to the media during Super Bowl week, the running back famously responded to all 29 questions with a variation of the same answer: “I’m here so I won’t get fined.” During last year’s All-Star game, the usually mild-mannered and beloved Kevin Durant lashed out at reporters. “You guys really don’t know shit,” he told them in response to a question about the job security of then-Thunders Coach Scott Brooks. “To be honest, man, I’m only here talking to y’all because I have to.”

These flashes of rudeness — probably best described as “honesty” — pointed to a breakdown of the tacit understanding between players and the press. The old, unspoken agreement was simple: sports teams got coverage, which translated into ticket sales and publicity, while the press got access, which brought in readers who were, inexplicably, eager to hear whether or not their favourite athlete had given 110 per cent. The transaction was mutually beneficial. And while the press has always pissed off pro athletes, they were willing to cooperate with reporters that were sometimes irritating, often meddlesome, and occasionally outright malicious because it was the sole way of disseminating a message to a mass audience.

A truth that has become painfully obvious but is usually left unsaid out of some mixture of politeness and embarrassment: players no longer need the media.

This is no longer the case. Social media allows athletes a direct line to fans. At the same time, newspaper readership is in freefall. And so the balance shifts: athletes create content that people want to read and in return they get…what, exactly? A couple of quotes in some quickly forgotten USA Today piece?

For athletes like Durant and Lynch, it’s obvious that playing the usual media game brings them little benefit. They are forced to talk with the press, however, because for sports leagues, at least, it still makes sense to work with the mainstream media.

But this is changing too. At a symposium in Washington a few years ago, Wizards and Capitals owner Ted Leonsis laid out a vision for the future of sports that should make journalists nervous. “I used to live in mortal fear about what you would write. Now, I don’t care,” he told the Washington Post. “I think it’s something that you need to internalize: that we’re our own media company.” In Leonsis’ eyes, sports teams and the media aren’t partners working together out of mutual self-interest: they are direct competitors. “When someone goes to find out something about me or a team or a player, and they go to Google and they type that in. I want to learn how to get the highest on the list, and I’ve done that,” Leonsis said. “I don’t want the Washington Post to get the most clicks. I want the most clicks.” It feels like it is only a matter of time before Leonis or some other iconoclastic owner takes the logical next step. If you own valuable content, why allow competing media organizations into your locker rooms to profit from it?

Obviously this problem isn’t unique to sports. In a perceptive essay at The Awl, John Herrman calmly walks readers through the “access panic” that is currently roiling through all corners of the media. You can see it in political reporters’ frustration with Donald Trump, who shuts out journalists with a gleeful indifference that makes Bautista look deferential. You see it in celebrity journalism, where Kanye West can reach more people with a tweet than with a Rolling Stone interview. You see it in the grumbling of cultural critics, who are denied press showings of The Force Awakens because — as everyone knows but no one is quite willing to say — their opinions simply do not matter.

In sports journalism, though, the crisis is particularly acute. Sports are exclusively media events — performances designed for public consumption that are constantly tweaked to make them as fascinating and dramatic as possible. For years, a fan’s relationship with the game has been mediated by the press. My vision of Sidney Crosby is an agglomeration of a thousand media narratives. A Warriors-Spurs mid-season game becomes infinitely richer when you’ve read a Sports Illustrated profile about Kawhi Leonard’s scarily locked-in personality or a feature about the trainers who quietly turned Steph Curry’s body into a shooting machine.

The stories all have the same function: to help fans better enjoy the game. It’s hard to argue that they’re essential. Like so many media arrangements that feel natural, the athlete-media compact may simply be an accident of history — an agreement made at a time when curious reporters happened to be the only ones with access to a printing press. It’s doubtful many fans will bat an eye if some other entity comes along to fill that function.

And they’re coming. Stephen Curry just co-founded a start-up called Slyce, a platform designed to help celebrities maintain their brand on social media by sifting through the deluge of postings to find the precise questions that they want to answer. Last year, the NFL player’s association announced that it was forming a media company called ACE, with “compelling sports-lifestyle content focused on athletes.”

In November, when Kobe Bryant announced his retirement, it wasn’t through ESPN or Sports Illustrated, but through a poem published on The Player’s Tribune, a new media site created by ex-Yankee Derek Jeter to give players full control over their message. If social media allows athletes to communicate their day-to-day thoughts and curate their own “brand,” the Player’s Tribune aims to do the work normally done by feature writers — creating the kind of long-form thumbsuckers that were once written by Serious Men who had spent their lives in the press box.

Of course, the end of access sports journalism doesn’t need to mean a future where fans are forced to digest pure, PR-managed spin. Freed from the need to ingratiate themselves with surly athletes, it’s possible sports writers will embrace the kind of in-depth analysis and cheeky commentary you already find from sports bloggers writing miles away from the locker room.

In the meantime, for those curious about Bautista’s feelings about the bat flip game, there already exists an in-depth piece on that insane inning. It describes the atmosphere in breathless detail, charting his thought process as he narrows his focus and feels a crowd “so loud that it was quiet.” It follows the controversy around the bat flip, and puts Bautista’s emotional, heart-on-his-sleeve playing style into the context of passionate Latin American baseball. It’s the best thing written about what it felt like to hit that historic homerun. It is, of course, a story published in The Player’s Tribune, by José Bautista.