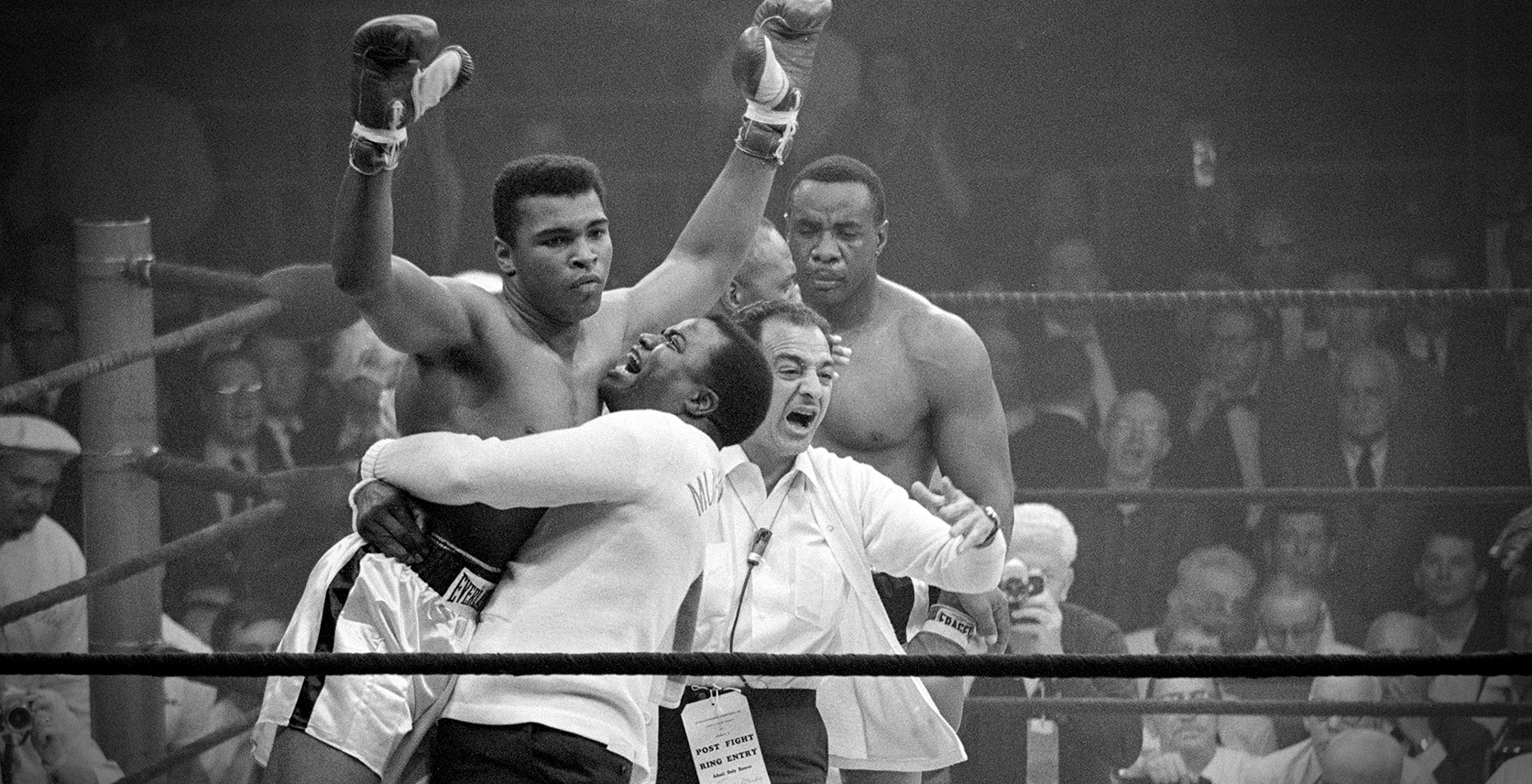

Here’s What Made Muhammad Ali’s Boxing So Timeless

Muhammad Ali won the world heavyweight title for the second time in 1974, 17 years before I was born. I saw it for the first time in my early teens on a DVD that came from a $5 box set I picked up in a Buffalo Walmart. Inside that punctured and tattered package were the moments that made the greatest athlete of the 20th century — the Fight of the Century, the Rumble in the Jungle, the Thrilla in Manila. Somehow, I didn’t need to know very much about Ali to recognize this.

I was hooked.

For a second, let’s forget all the things that allowed Ali to rise above the sport of boxing — his politics, beliefs, character. You can read about that in lots of other places, and you should. Here, I want to talk about boxing.

November 14, 1966 in Houston, Texas. Ali delivers perhaps the most beautiful beating a human being has ever received. The unlucky recipient was Cleveland Williams — a 6’3” thunder puncher who was recovering from a serious gunshot wound at the time of the fight. The bout is maybe the closest thing to a movie fight I have seen in real life. By that I mean Ali imposed his will on his opponent the way a director does on actors. Watch about 20 seconds into the first round, as Ali plants his left foot and slips under a left hook. Watch how effortlessly he bounces around the ring, as if the man in front of him is not trying to hurt him. Ali — not known for his economy of movement — didn’t waste an ounce in this performance: every shuffle precisely integrated into the flurry that followed, every head movement pulled the body into a position to strike.

The thing is, this is not how fighting is supposed to work. It broke every rule that was supposed to be unbreakable. Keep your hands up and you’ll get punched in the face less, for instance. How many kids got punched out because they went into a fight imitating Muhammad Ali? I did. Multiple times.

The Williams fight may have been considered a ballet, but the George Foreman fight was a true grind. And yet, somehow it was probably more impressive. Again, Ali appeared to break laws of causality. He did things that should have lost him the fight and won — not in spite of them, but because of them. A boxer who had made a career floating around his opponents sat on the ropes and allowed Foreman to tee off on him, whispering in his ear when he pulled him in for a clinch. Whatever your feelings about trash talking this needs to be acknowledged. Do you know how hard it is to keep talking while you’re being punched repeatedly in the face and gut by a man who could probably knock out a large farm animal? Seriously. Do you? I don’t.

Before the first fight between Ali and Frazier, Norman Mailer wrote that the fighter goes through experiences in the ring that are immense and incommunicable. Here is his attempt to communicate it: “Two great fighters in a great fight travel down subterranean rivers of exhaustion and cross mountain peaks of agony, stare at the light of their own death in the eye of the man they are fighting, travel into the crossroads of the most excruciating choice of karma as they get up from the floor against all the appeal of the sweet swooning catacombs of oblivion…”

His point was that boxing was its own language, one that is “as detached, subtle and comprehensive in its intelligence as any exercise of the mind.” Ali was defined by his personality, his trash talk, but if you frame it the way Mailer does, it becomes a translation from a language all non-fighters are helpless to understand. Ali’s cheap rhymes and perfectly quotable phrases made him a poet in some sense of the word. But he was also one in the metaphysical sense — boxing’s high poet. In matters of the ring, he defined his universe.

The surest proof of this is the fact that in the golden age of heavyweight boxing, every fighter has had their entire career distilled to the moments they squared off against Ali. George Chuvalo is the iron-jawed Canadian Ali couldn’t put down. Ernie Terrell is the man who refused to call him by his Muslim name. Michael Dokes is the man who couldn’t hit him. Countless others will be remembered only for being knocked out. Only Frazier seemed to defy these simple categorizations, but even he couldn’t escape Ali. Nor, some might argue, did he really want to.

“Frazier passing and then losing Muhammad — which was the greatest piece, I call him the greatest piece because we were all just one guy; we didn’t exist without the other,” said Foreman shortly after Ali’s death. For him, the impact was even more profound.

“My life will not be the same now,” he said. “Too much of me will be missing now.”