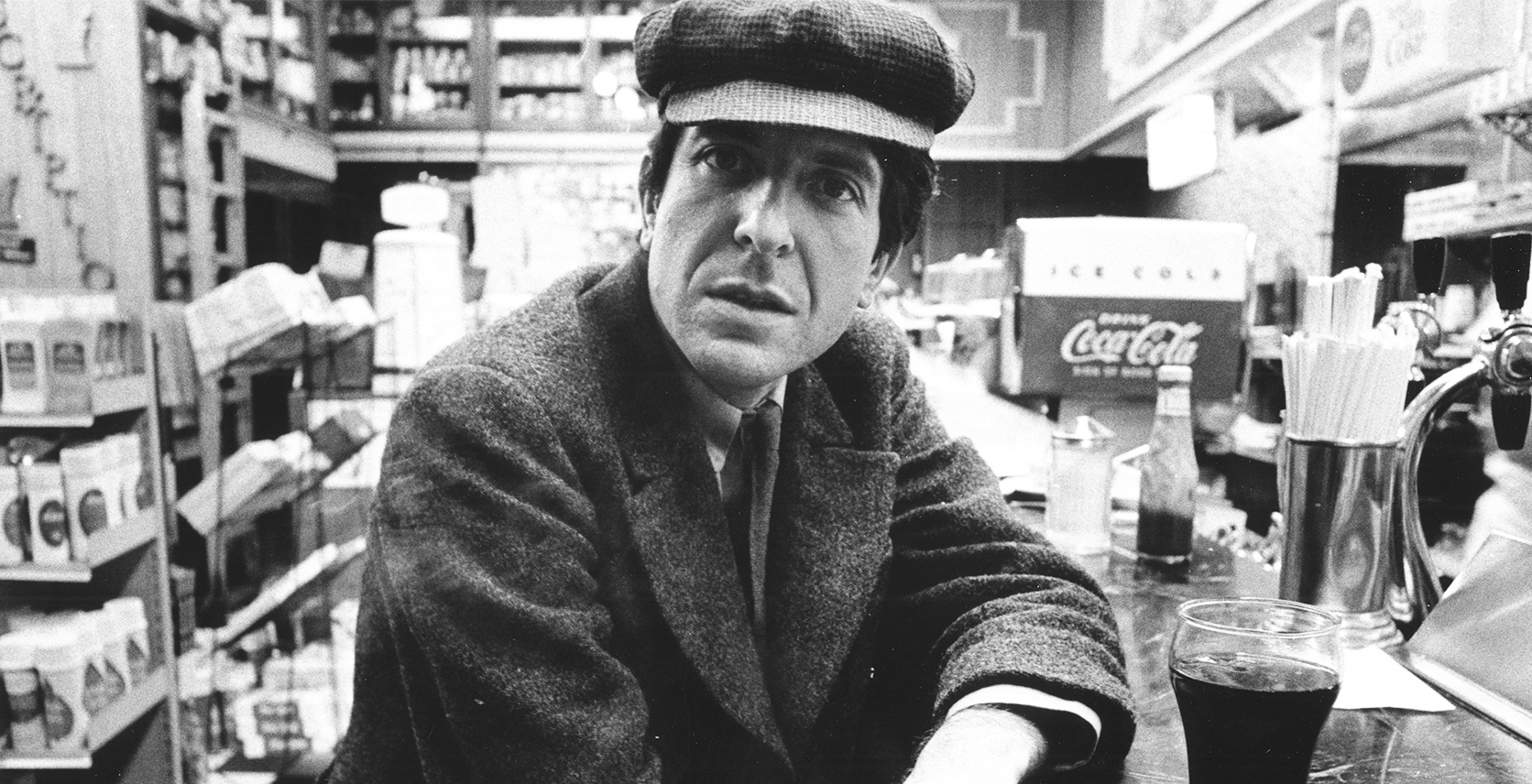

Leonard Cohen Will Always Be a Beacon in the Darkness

Leonard Cohen — poet, songwriter, Canadian, nervous wreck, human aphrodisiac — has died at the age of 82. In a week we all thought couldn’t get any darker, this feels like a total, Apocalypto-esque eclipse.

Emerging in the late ’60s with Songs of Leonard Cohen, the stoney-voiced troubadour would become one of the world’s greatest songsmiths — Bob Dylan once told Cohen he considered him his nearest rival. (Full disclosure: I think Cohen was better.) His passing comes just weeks after the release of his final album, (ironically) titled You Want It Darker, and shortly after he’d written a goodbye note to his ailing ex and lyrical muse Marianne Ihnlen, telling her, “it’s come to this time when we are really so old and our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon.”

My favourite anecdote of the Lord Byron of Rock n’ Roll is a time he royally fucked up. At the end of his 1972 world tour, standing on stage at the Yad Eliahu Sports Palace in Jerusalem, Cohen only managed to intone the first three words of “Bird on a Wire,” fumbling when the audience began to applaud. “I really enjoy your recognizing the song, but… I’m scared enough as it is up here, and I think something’s wrong every time you begin to applaud,” he told the crowd. “So if you do recognize the song, would you just wave your hand?” He strummed idly, but what first came off charming stage fright now looked more like actual anxiety. “I hope you’ll bear with me. These songs are kind of, uh — they become meditations for me, and sometimes, you know, I just don’t get high on it, and I feel that I’m cheating you. So I’ll try it again, okay? And if it doesn’t work, I’ll stop in the middle. There’s no reason why we should mutilate a song just to save face.”

Cohen began singing “One of Us Cannot Be Wrong.” More applause. And this time he fell apart. “Now look, if it doesn’t get any better, we’ll just end the concert and I’ll refund your money, because I really feel that we’re cheating you tonight,” he said. “You know, some nights, one is raised off the ground, and some night, you just can’t get off the ground. And there’s no point in lying about it. And tonight, we just haven’t been getting off the ground.” He apologized a bit more, referenced the Kabbalah, then walked off stage.

Backstage, as captured in Tony Palmer’s surprisingly candid 1972 documentary Bird on a Wire, Cohen was an agitated, sobbing mess. He told his band and crew that he couldn’t go on, and that they should refund the audience. The pressure of performing the final stop of his tour in the Holy Land had gotten to him. His managers pleaded with him to reconsider. He wasn’t having it. But after hearing the young audience chant the Hebrew song “Zim Shalom” (“We Bring You Peace”), Cohen thought maybe what he needed was a shave; rummaging through his guitar case for a razor, he found an old envelope full of acid. “Should we not try some?” he suggested to his band.

Cohen returned to the stage to a riotous welcome. He started playing “So Long, Marianne,” and the LSD kicked in hard. “I see Marianne straight in front of me and I started crying,” he recently recalled to The New Yorker. “I turned around and the band was crying, too. And then it turned into something in retrospect quite comic: the entire audience turned into one Jew! And this Jew was saying, ‘What else can you show me, kid? I’ve seen a lot of things, and this don’t move the dial!’ And this was the entire skeptical side of our tradition, not just writ large but manifested as an actual gigantic being! Judging me hardly begins to describe the operation. It was a sense of invalidation and irrelevance that I felt was authentic, because those feelings have always circulated around my psyche: Where do you get to stand up and speak? For what and whom? And how deep is your experience? How significant is anything you have to say?”

Cohen wouldn’t finish the show. He was too overcome with the sense that he was phoning it in, and lacked the heart to deceive his fans. In a musical landscape where it’s commonplace for bands to go through the motions to canned backing tracks, or for rappers to rely on armies of ghostwriters, that’s rare. The bard’s onstage meltdown, while an example of just how anxious a guy he could be, is also a testament to his integrity. He offers a model for living with dignity and truthfulness, without succumbing to illusions, without giving in to mediocrity or indifference, without masking failures and flaws in a world that too often feels built on smoke and mirrors. Cohen was the Real Thing, the genuine article. He’s gone now, but he’ll forever be a reminder, even as darkness seems to envelope us, to always look for the crack in everything, where the light gets in.

Also: when it doubt, maybe don’t drop acid.