For the Sake of Men Everywhere, We Need to Stop Policing Pro Athlete Friendships

A few weeks ago, on the eve of the annual collapse of the Los Angeles Clippers, ESPN’s Kevin Arnovitz published a eulogy to the Lob City era. With core members of the team becoming free agents this summer, the team’s first-round exit felt like the death rattle of one of the NBA’s most frustrating, talented, perennially underachieving teams. The curse of the Clippers, Arnovitz wrote, wasn’t racist former owner Donald Sterling after all. It was “the dynamic” — a vague term meant to encapsulate the web of “interpersonal relationships that inform the Clippers’ mood.”

Over thousands of words, Arnovitz investigates this dynamic, interviewing people on and off the record to probe the ever-shifting relationship between the team’s stars Blake Griffin and Chris Paul. “They both made a concerted effort this past summer to figure each other out,” one anonymous source breathlessly reveals. Griffin had a serious realization that “communication is a logical way to bridge the distance — and there had been distance.” The piece is a scrupulously reported investigation into a simple question: are Blake Griffin and Chris Paul, like, friends?

Sportswriters are obsessed with friendship. In the NBA especially — a league built on the skills and charisma of a relatively small number of individuals — the media tracks the relationships of professional athletes with the fevered glee of gossip reporters following Hollywood romances. When Kevin Durant left Oklahoma City and teammate Russell Westbrook last offseason, the media covered the free agency decision the same way it covered the Brangelina split — scouring the players’ social media accounts for signs of hurt feelings, obsessing over body language, endlessly questioning friends and surrogates to evaluate who had won the divorce.

Of course, serious sports journalists never admit to being obsessed with whether two grown men are pals. They are not reporting something as frivolous as personal affection. Instead, they talk about “chemistry” if they’re referring to friendship between teammates. They complain about players “getting soft” if they’re roasting them for befriending opponents.

But the truth is that one of the reasons we follow sports is because professional sports are the most public stage on which we see relationships between grown men play out. While the media serves up endless examples of romantic partnerships and celebrity female friendships — with pics of Taylor Swift’s rotating cast of BFFs threatening to overwhelm the internet — public examples of genuine male camaraderie are harder to find. The reason the friendship between Barack Obama and Joe Biden became a meme, spawning mountains of social media fan-fiction that imagined heartwarming scenes from their bromance, was because their obvious affection for one another was so novel.

Professional sports are the rare space where we can follow male relationships during the on-going reality TV show that is a season of basketball or baseball. And when it comes to friendship in the sports world, as with all cultural questions of the last decade, LeBron James is the central, controversial figure. When he entered the league, James offered a new model of male friendship. Earlier superstars were famously stand-offish, their lone-wolf routines pitched as an essential part of what made them great competitors. Michael Jordan was an exacting bully who punched teammate Steve Kerr in the face and famously reduced rookie Kwame Brown to tears by ritually humiliating him in front of his teammates. Kobe Bryant cultivated the image of a solitary superstar too committed to winning to care about relationships. “Friends come and go but banners hang forever,” Bryant once said, presumably test-driving a slogan for his Black Mamba brand.

James is different. No player has ever put such a premium on friendship and no player has ever had his relationships analyzed with such fervour. When James left the Cavaliers to play with friends Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh, he was castigated for lacking a competitive edge, the team mockingly labeled the “Super Friends.” “There’s no way, with hindsight, I would’ve ever called up Larry, called up Magic and said, ‘Hey, look, let’s get together and play on one team,” Michael Jordan scoffed. “LeBron has never had that killer instinct and that competitiveness,” bemoaned a Bleacher Reporter writer. “LeBron just wants to be one of the guys instead of The Guy.”

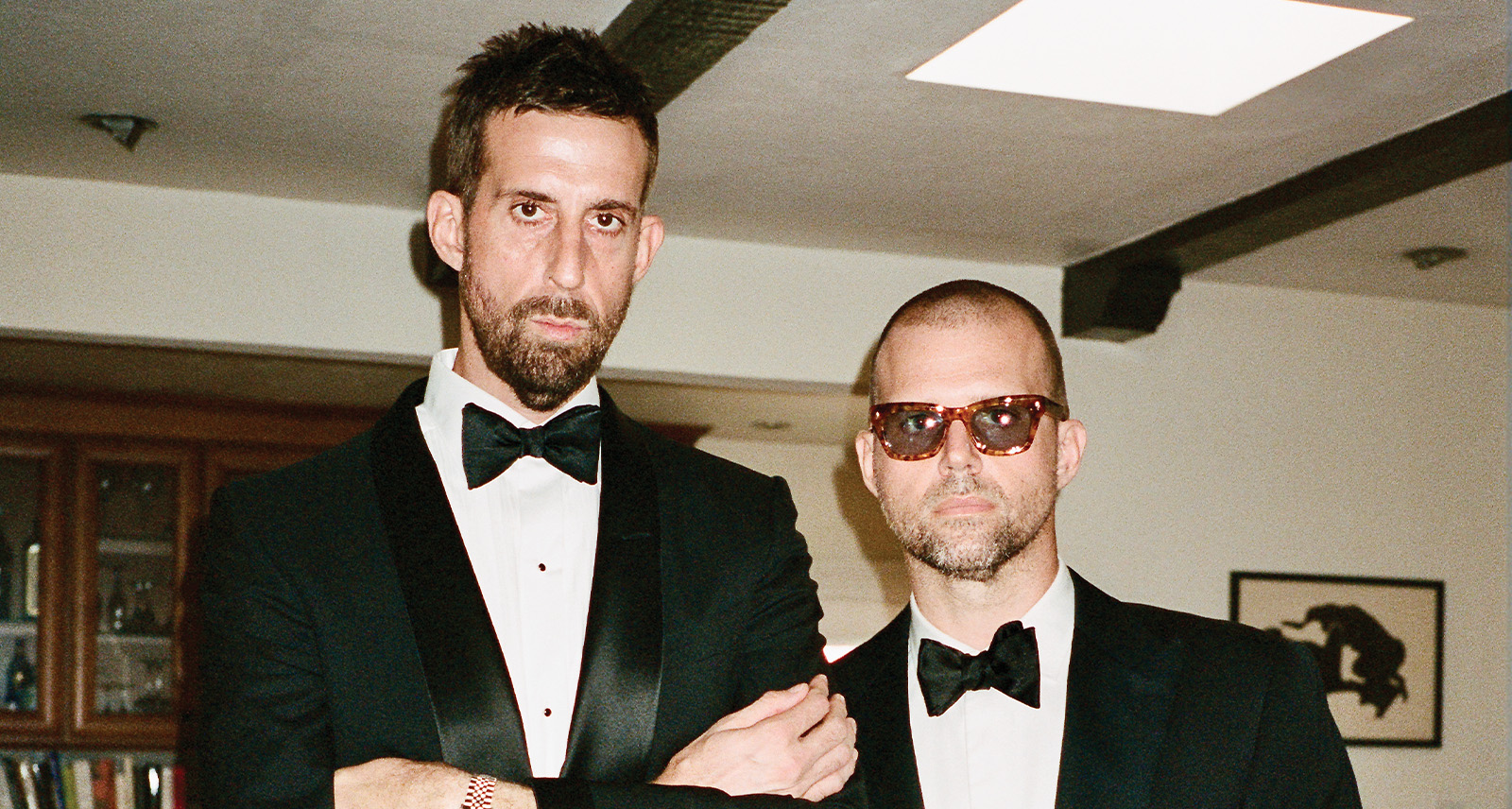

Winning three championships hasn’t quieted the critics. Last year, after James was found “fraternizing” during halftime with Wade, now an opponent, old-school sportswriters pounced. “James might need to consider suspending that relationship,” wrote a columnist at the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “It just makes me ill,” Cedric Maxwell, the player-turned-commentator told ESPN when asked about the Wade-James friendship. “It’s against the rules of nature. Why would you have a giraffe among the lions?” When an image emerged of James, Chris Paul and Dwyane Wade straddling a Banana Boat in bathing suits — it became the iconic image of all that was wrong with the modern NBA. Instead of hating one another, like Bird and Magic used to, modern stars were hopelessly compromised by their suspect relationships.

This policing of male friendship feels like the final gasps of a defensively macho era of sports fandom. It carried with it more than a whiff of homophobia — a discomfort with male intimacy and a fear that it will somehow make a person soft, weak. And it’s an attitude that has proven destructive. Study after study has found that as men age they lose intimate friends. Relationships between men built on sharing activities or routines — playing pick-up soccer together or sharing an office — often disappear when those activities fall away. And friends aren’t some frivolous luxury. A 2005 Australian aging study found that strong friendships, even more than family relationships, increased life expectancy.

It’s a fact that LeBron James and a new era of athlete seem to understand implicitly. A 2015 feature by Pablo S. Torre revealed a friendship between James and Dwyane Wade that is intimate and complex. Wade allows James (but not his wife) to order for him at restaurants. They talk to one another late at night on the phone, signing off with a “love you, bro.” To Wade and James, the idea that that kind of bond should be provisional — secondary to their job, something that could be “suspended” in order to mollify the sportswriters of Cleveland — is inherently ridiculous. “We always say, ‘One day, we’re gonna stop dribbling this basketball,'” Wade says. “And yeah, while we’re playing against each other, we’re going to compete and we’re going to have fun. But life goes way beyond this.”